Euro-skeptic Italian populists are posing a serious threat to the European Union. Following the drama over Greece and Brexit, the political situation in Rome could throw Europe into its next major existential crisis.

He has become his country’s most important politician since the election. At the same time, he has become Europe’s most-feared bogeyman. Now, he is seeking to become a statesman.

Matteo Salvini, 45, the leader of the Italian right-wing nationalist party Lega, has been promising for years that he would lead Italy out of the eurozone if he ever got the chance — and it initially appeared that he would be unable to form a government because of his insistence on appointing a finance minister who advocated leaving the common currency zone. But now, Salvini is doing all he can to demonstrate that he doesn’t actually have anything against the euro after all.

On Wednesday, a painting crew drove up to Lega headquarters on Via Bellerio in Milan. For years, the words “Basta Euro” had been emblazoned on the wall in massive letters. End the euro. But this week, that message was literally whitewashed, as if the words had never existed.

“Basta Euro”? Did someone actually make such a demand? Surely not Salvini, who once said about the euro: “We don’t need a referendum. If Lega enters the government, we’re out.”

Even as the painters were still at work, Salvini’s supporters were celebrating at Milan’s central station – popping the corks of bottles of prosecco and dreaming of winning 30 percent of the vote in the snap elections that briefly seemed inevitable. The crisis in Italy is visible, they say, and you can even see it in the train station. “All the unemployed and clandestini,” they say, citing the term used to describe illegal sub-Saharan Africans they claim loiter about day in and day out, “groping our women and disturbing the cityscape” – it all needs to be stopped.

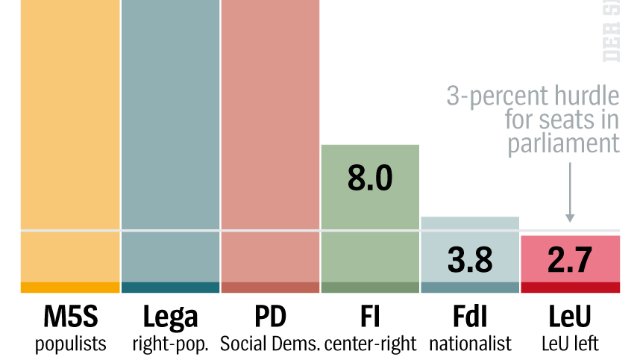

Salvini has played a masterful game since the March 4 election. Although the Five Star Movement (M5S) technically got the most votes, it is Salvini who has emerged as the clear winner during the 90 days it has taken to form a new government. His party has risen by 10 points in the polls to 27.5 percent and he dropped his original coalition partner, Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia, in favor of an alliance with M5S.

A Fan of Putin and Euro Foe

It paid off. After several crazy weeks and a significant amount of back-and-forth, Salvini has prevailed as the undisputed leader of the right-wing camp, perhaps even the most powerful man in Italy. Salvini, a fan of Vladimir Putin and foe of the euro, an anti-migrant politician and a defender of Mussolini — and a man who also likes to lash out at Germany from time to time.

He played his game of high-stakes poker with virtuosity, posing as a victim of the Italian president (who must formally approve his government) and of the establishment, threatening new elections and ultimately entering into a coalition with the Five Star Movement.

Now Paolo Savona, the common currency opponent President Mattarella rejected as finance and economics minister, has been installed as minister for European Affairs. Salvini has taken over the Interior Ministry, his coalition partner Di Maio the Labor and Development Ministry. And lawyer and university professor Giuseppe Conte is prime minister.

Quite a few commentators believe that Salvini deliberately provoked this week’s crisis. If new elections were to be held in the coming months, which is not unlikely given this imbalanced coalition, then he would probably win. For opponents of the populists, all that remains is the hope that the new government will prove chaoticand that people will quickly grow disenchanted with it.

Italy no longer has a strong liberal, moderate or left-wing opposition: The traditional parties and the well-known centrist politicians have mostly lost their credibility. The picture of Italy at the moment is indeed a tragic one, standing as it does for the failure of politics, but also for the longer term consequences of efforts to save the euro, which have strengthened extremists well beyond Italy’s borders.

Will these two populist parties, as dissimilar as they are, really now strive to leave the eurozone or even the EU, or are their most recent denials to be believed? And what happens if they honor their pledge to spend billions on social benefits and simply ignore the EU Stability Pact and its restrictions on deficit spending?

The stakes could harldy be higher. Not only is the future of the eurozone’s third-largest economy suddenly uncertain, but the euro’s very survival could be at risk. The euro crisis has been contained for several years now, but it could return very soon — and much larger. Last time, it was “just” Greece.

Europe’s Horror Scenario

If Salvini and Di Maio drive up Italy’s sovereign debt load — already far in excess of 2 trillion euros — as they have indicated they will, a dynamic will be put into motion that would be difficult to stop. The European Central Bank would no longer be allowed to keep buying up Italy’s sovereign bonds, interest rates on those bonds would skyrocket and the country could face bankruptcy. And given Italy’s size, a bailout is a virtual impossibility.

This is the horror scenario Europe has feared for years. And it could materialize extremely quickly. The first warning signs are already visible. The spread, or interest rate gap between 10-year Italian and German government bonds, has already almost tripled, and the Milan stock exchange has recorded billions in losses.

Still, the markets remained relatively calm on the news that a governing coalition had been forged. Investors, it seems, would rather see a populist government than snap elections. And it’s very possible that it will be some time before the first major altercation between Rome and Brussels, perhaps around the time that negotiations get serious over the next Italian budget. Some may also be reassured by the fact that three important members of the new cabinet are essentially technocrats rather than members of the two parties.

Leading that list is Conte, who was sworn in on Friday along with his cabinet, but also incoming Foreign Minister Enzo Moavero Milanesi, who served as a member of Mario Monti’s technocrat government. And then there’s Giovanni Tria, the economics professor chosen as finance minister. He isn’t in favor of leaving the euros, but he has, in the past, called for Germany to leave the common currency because its trade surplus is incompatible with the eurozone. He also advocates public financing through the European Central Bank, a practiced banned under EU treaties. He certainly can’t be described as a moderate.

Europe’s banks have already begun suffering from the chaos in Rome because they have to offer buyers higher interest rates when selling their own bonds. German financial institutions are also anxiously eyeing developments with their $91 billion in outstanding debts that are held in Italy. With $311 billion in outstanding debts in Italy, only French banks have greater exposure in the event of defaults.

But the situation is most threatening for Italy itself. Commercial banks, the central bank and government and retail investors are more closely interconnected in the country than elsewhere. Some 48 percent of all government bonds, well over 1 trillion euros, are held by Italian banks, insurers and small savers. A further 20 percent are parked at Banca d’Italia.

Those are just the economic challenges, and they are bad enough. Europe is currently battling on many fronts, both internally and externally. The EU must adopt a united stance on Donald Trump, whose misguided policies threaten both Europe’s security and prosperity. Trump is forcing Europe into a trade war and, worse yet, he threatens to scrap the postwar international order that enabled the Europeans to find their place in the world — through trade and the structures of the World Trade Organization and the security it found in the form of NATO.

But how can the EU wage a trade war if Italy threatens to spiral into chaos? At a time when the EU could be proving itself as an alternative to Trump’s unilateralism, when Japan, Mexico and the members of South America’s Mercosur are lining up to conclude free trade agreements with Brussels, Europe may instead be facing months, if not years, of squabbling over a possible bailout for Italy. And then, almost as an afterthought, there’s Brexit, Britain’s departure from the EU, which is set to take place in nine months.

The attention instead is on Italy, a founding member of the EU, a pillar of NATO and the third-largest economy in the eurozone. If this country teeters, it will shake the entire architecture of the European Union.

A Window of Opportunity Closes

The fact that the EU never had the strength to undertake fundamental reforms of the economic and currency union after it barely managed to keep Greece in the eurozone has now come back to haunt it. And that’s not even to mention the fact that Chancellor Angela Merkel has never offered a proper response to the ideas for European reform forwarded by French President Emmanuel Macron.

The window of opportunity for tackling those reforms had always been narrow. In light of the crisis in Italy, however, it now appears to be closing. Even optimists expect little more than minimal consensus at the important EU summit at the end of June. The fear of Italy’s collapse will now make it that much harder for Merkel to reach out to Macron. After all, it seems unlikely that German conservatives would agree to a new crisis fund of the kind Macron is demanding at the same time as a real crisis is developing. The EU wanted to kick into reform gear together with Macron, but now Italy is pulling the community back into the maelstrom of crisis.

This applies not only to eurozone reforms, but to almost all major political projects. The desired deal on asylum law, e.g., the decision of whether and under what conditions EU member states can be required to take in migrants, is once again uncertain, even though it would be in Italy’s best interest as one of the country’s most affected by the refugee crisis.

The Italy crisis is a convergence of the two greatest challenges facing the EU: the economic threat to the eurozone and the erosion of shared values and norms. If the populists now govern in Italy, the country could steer itself on a course of constant confrontation with Brussels — by for example, expressing its solidarity on key issues with right-wing populists in France, Austria or Finland or with the EU-critical governments in Hungary and Poland.

Or it could take the side of half or full-on autocrats like Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin and undermine European unity in the process. Some potential issues where it could do so include the Iran agreement, the trade tariffs imposed by Trump, the extension of sanctions against Russia, climate policy or even the European approach to China.

Bad News for the Continent

The revival of nationalism in Europe, particularly in Italy, is bad news for the Continent. If the EU ever had one great, overarching goal, then it was to counter national self-interest with the vision of a transnational community of values. What will hold Europe together if that foundation is shaken?

And all this comes at a time when Trump and Putin are trying to tear down the multilateral order, established over many years through painstaking work, and instead insist on the survival of the fittest. By withdrawing from international treaties, violating international law, launching trade wars, waging real wars and annexing parts of neighboring countries. A world, in other words, in which the EU ought to serve as a bulwark, as a bastion of reason. But that’s not a role the EU will be able to play if men like Salvini set the tone in the future.

But to truly understand the roots of the Italian crisis and the reasons for populist success in the country, you have to look beyond Rome — all the way to Sicily, the poorhouse of Italy.

‘Pressure from Europe’

Sitting in a smalltown south of Etna on an early summer day, Teresa Lauria, 32, voices her anger about how Italian President Mattarella at first tried to keep her party, the Five Star Movement, out of government. Lauria says there were other forces at work, “pressure from Europe and also from Germany.”

Lauria has been active with the Five Star Movement since 2012. Her father was a communist, “like practically all workers in the city,” she explains. Lauria herself is running for mayor in Priolo Gargallo, where the election is scheduled to take place on June 10. Some 72 percent of voters here cast their ballots for M5S in the national election in March, the party’s strongest showing anywhere in the country. “There was mass euphoria,” says Lauria.

Priolo Gargallo is located in the middle of a huge industrial area, where the chimneys of the factories tower at the ends of the streets. Local petrochemical plants and steelworks once employed 30,000 people. Today, not even half that many people have work. The area around Priolo Gargallo has been dubbed the “triangle of death” because of the toxins in the air, water and soil here.

A few years ago, the city government set up a kiosk in the city center, the “House of Water,” so that all residents would at least have access to clean drinking water free of charge. Every resident has the right to fill up on filtered water there. Antonello Rizza, who had been mayor for years, proudly named the facility after himself.

But Rizza is longer able to visit it, as he’s currently being held under house arrest. A few months ago, he was driven out of office for corruption and other allegations. But those aren’t Sicily’s only problem — it also has persistently high unemployment. The rate for Mezzogiorno, as southern Italy is called, is 19 percent compared to a national average of 11 percent. More than half of the young people in the south are jobless. Many who have gone to college leave to find better conditions and pay elsewhere. The average per capita economic output in the south is 18,600 euros, a little more than half the northern Italian average of 34,000 euros.

Lauria doesn’t naively believe that the Five Star Movement can suddenly pull an economic miracle out of its hat. “But people trust us to be honest and do something to ensure a better future,” she says. “With our idea of a modified flat tax, we could provide enduring economic stimulus in the south.”

She believes Europe’s influence on Italy is “far too great,” that her country is being overly patronized and that other Europeans lack solidarity for Italy. Lauria cites the refugees who come via the Mediterranean Sea as an example. “Many countries have built walls to protect themselves, but they do nothing for us.” She says she used to always imagine the EU as being like a “big family, but it isn’t.” In short: “The others are playing a game and Italy is not a part of it.”

Lauria’s campaign relies on direct contact with voters. On a recent Tuesday evening, she drove the city in a Fiat Panda that she has converted into her campaign vehicle. She stopped repeatedly to talk to passersby and to explain the policies she would pursue as mayor. “We don’t want to be a people of freeloaders!” is one of her most popular messages. “We’re not the freeloaders, the freeloaders are the politicians who take money from the people but give nothing back.”

This article was published by Der Spiegel on the 1st of June 2018. It was written by Der Spiegel staff