COP, COP, COP and COP … focusing on forests and migration.

Attenborough, Mottley and Thunberg rattle cages in Glasgow. Brazil’s emissions are increasing because it’s chopping down the Amazon but it’s joined a global agreement to stop deforestation by 2030. World Heritage forests become carbon sources. Rich countries building a ‘Global Climate Wall’ to keep climate migrants out.

Glasgow highlights

To start, a few snippets from the first week of COP26:

David Attenborough’s rallying call at the opening session included: “If working apart we’re a force powerful enough to destabilise our planet, surely working together we are powerful enough to save it.”

Mia Mottley, Prime Minister of Barbados, told the 200 world leaders in Glasgow that the wealthy countries need to provide developing countries not the currently promised $US100 billion per year but $US500 billion for twenty years to help them mitigate and adapt to climate change. “Failure to provide the critical finance is measured, my friends, in lives and livelihoods in our communities. This is immoral and it is unjust.”

Greta Thunberg fired up the real leaders, those in the streets. “No more blah blah blah.”

In the lead up to the Melbourne Cup Australia won a Fossil of the Day Award for bringing no new emissions reduction targets and no plans to phase out fossil fuels to Glasgow and failing to sign the pledge to reduce methane emissions by 30 per cent by 2030 – thank you, Barnaby, we have you to thank for that. And would you believe it, Australia won another the next day for “excelling in heading for rock bottom this COP”.

If you’re getting lost in all the jargon, here’s a two-page cheat sheet.

Deforestation increases Brazil’s emissions

Like most large and wealthy countries, Brazil’s energy-related greenhouse gas emissions fell by around 5 per cent during 2020 as a result of the economic downturn associated with COVID. But unlike most other countries, Brazil’s total emissions did not fall by a similar amount — rather, they increased by 9.5 per cent. No prizes for guessing why — because deforestation of the Brazilian forest (mainly in the Amazon) increased by 24 per cent compared with 2019. Almost 11,000 square kilometres (about the size of Greater Sydney) of forest were cleared, producing in the Amazon alone almost 800 million tonnes of CO2e (carbon dioxide equivalent). If the Amazon were a country, it would be the ninth largest emitter. Within Brazil, land use change accounts for almost half of all greenhouse gas emissions. Add in the emissions from agricultural practices and the total is almost three quarters. A decade ago Brazil was getting on top of deforestation but under Jair Bolsonaro environmental controls and monitoring have been dismantled and land grabs for mining, agriculture and logging have increased dramatically.

The 9.5 per cent referenced above refers to Brazil’s gross CO2 emissions but to avoid any accusation of biased reporting, their net emissions (i.e. after allowing for the CO2 absorbed by the forests) also increased, by an even greater 14 per cent between 2019 and 2020.

World Heritage forests become sources of CO2

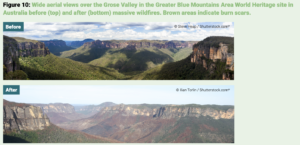

Having just read that, you might be surprised to learn that none of the Amazon’s World Heritage forests is among the 10 listed forests that, because of human activities, emitted more carbon dioxide than they absorbed between 2001 and 2020. But, shock horror, the Greater Blue Mountains Area is among the 10 — an unwelcome attribute shared with, amongst others, Yosemite and Grand Canyon National Parks in the USA, and tropical rainforests in southeast Asia, Central America and the Caribbean. It is, of course, inevitable that as climate change and deforestation progress further in the foreseeable future, these ten forests and more will act less and less as sponges for anthropogenic CO2 emissions.

All UNESCO’s World Heritage listed forests, covering an area slightly smaller than NSW, absorb 190 million tonnes of CO2 per year, equivalent to two-fifths of Australia’s annual emissions. And here Australia can claim some credit. The World Heritage Tasmanian Wilderness Area, occupying much of western Tassie, is the largest carbon sink among the listed forests, responsible for absorbing a net 21 million tonnes of CO2 per year. Kiwi readers will be pleased to learn that Te Wahipounamu in the southwest corner of the South Island of New Zealand is second (13 million).

UNESCO identifies three pathways to help World Heritage forests (“living laboratories for monitoring environmental changes”) continue to be strong carbon stores and sinks: 1) prevent devastation caused by climate-related events by having disaster risk reduction initiatives, climate change adaptation plans and rapid response fire management programs at all sites; 2) avoid fragmentation of forests to maintain ecological connectivity and carbon storing capacity; 3) integrate World Heritage sites into national commitments to international initiatives such as the Sustainable Development Goals, Paris Agreement and Global Biodiversity Framework.

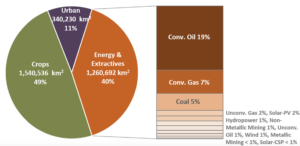

One piece of good news to emerge from Glasgow this week has been the agreement of over 100 nations to end and reverse deforestation by 2030. For once, Australia was on the right side of history and signed on. The agreement is much needed because continuation of the world’s “business-as-usual” land clearing between now and 2050 will see an area the size of Queensland and the NT cleared. Agriculture would be the largest cause of land conversion (an area slightly smaller than Queensland), closely followed by energy and extractive industries (an area slightly smaller than the NT), with urban development making up the remainder. The figure below displays this graphically.

When looking specifically at intact natural land, the energy and extractive industries will be responsible for 75 per cent of the conversion (i.e. destruction). This constitutes the major threat to biodiversity and environmental integrity. Africa is by far the region likely to experience the most land conversion (over 1 million square kilometres — slightly larger than South Australia).

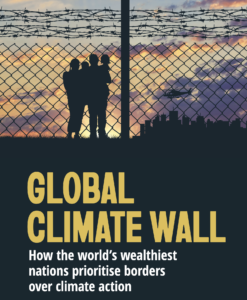

Global climate wall to repel climate migrants

The BBC is producing a series of 3–5 minute videos called Life at 50C. Each one focuses on the experiences of people already enduring high temperatures and being forced to make decisions about not just how they live but where. For instance, rising temperatures and desertification in the Sahara are destroying communities and forcing people to move to the coast, and heat and drought are having serious health effects on people in Mexico, compounded by upstream damming of the Colorado River in the USA. The effects of bushfires in Australia are also featured.

The majority of people who are displaced from their homes whether by climate change or other factors move to somewhere within their own country. But as we know, some cross international borders. Both domestic and international climate-related migration, which primarily affects low income countries, will increase as global warming increases. So how are rich countries responding to the increasing flow of climate migrants to their borders? Taking steps to limit global warming? Helping poor countries adapt to climate change? Providing humanitarian assistance to migrants? Yes, yes and yes to limited degrees but looking at how they are spending their money tells a different story.

Militarising their borders is the main response. Seven of the biggest emitters of greenhouse gases, responsible for almost half of the world’s historic emissions — USA, Germany, Japan, UK, Canada, France and Australia — collectively spent over twice as much on border and immigration enforcement (over US$33 billion) as on climate finance to help poor countries mitigate and adapt to climate change ($US14.4 billion) during 2013–2018. Canada (15 times more), Australia (13 times) and the USA (11 times) were the standouts. During this period, the seven have increased their border protection spending by almost a third. They have prioritised building a “Global Climate Wall” to keep out victims of climate change rather than tackle the crisis that has caused them to flee their homes.

The beneficiaries of lots of this extra money have, of course, been the consultancies, arms manufacturers, security and surveillance companies, construction companies etc. contracted to do the work. This ‘border security industry’ has not been sitting back idly waiting for the work to come along. They’ve learnt from the fossil fuel companies, big agriculture and big pharma, and they’ve been working hard on public and politicians, talking up the risks and lobbying for more programs and funds to stop the migrants. And with climate change going from strength to strength and climate migrants set to increase markedly in the coming decades, their future is looking secure. In fact, many of the companies that provide border security also provide security to the fossil fuel industry and the boards of fossil fuel companies and border security contractors often have cross-over members. Quite a win-win: create the climate problem that causes people to migrate from poor countries and provide the services to keep the migrants out of the rich countries that have benefited most from fossil fuels and now won’t provide funds to help the poor countries deal with climate change — brilliant!

Bushfires in the Grose Valley

Finally, courtesy of the UNESCO report, pictures of the Grose Valley before and after the bushfires.