Environment: Prescribed burning makes bushfires worse

Jul 23, 2022

Prescribed burning does more harm than good, as do fossil fuel subsidies. How to protect wild species.

Prescribed burning

The Saturday Paper carried an interesting piece last weekend on the merits or otherwise of prescribed burning to avoid bushfires.

It’s good old common-sense, really! If you want to reduce bushfires you must reduce the fuel load and you do that by prescribed or hazard-reduction burning. Just one problem: the evidence doesn’t support the common-sense. Or at least, only in very limited circumstances is prescribed burning effective – specifically, localised burning close to properties on the urban fringe can be effective. However, the benefit doesn’t last long and the burning needs to be repeated at short intervals.

Large-scale prescribed burning in bushland and forest may decrease the risk of a bushfire temporarily but then it makes the forest more flammable and increases the risk of a fire for several decades. This is because prescribed burning stimulates the growth of ground-level plants, many of which burn easily, and reduces the canopy which lets the wind through and encourages fire spread. Better to leave things alone, stop undermining the natural forest processes and let self-thinning occur in a decade or so. Older undisturbed forests are least likely to burn. Evidence shows that bushfires are strongly associated with recent prescribed burning.

Rather than continuing to support the prescribed burning industry, it makes more evidence-based sense to let the forests age and self-thin and invest in satellite technology and drones that identify the location of bushfires early, when they are small, and then drop water on them with pinpoint accuracy – ‘shifting budgetary focus from lighting fires to fighting them’. Despite the evidence, this may well prove to be a hard argument to win.

Sustainability of wild species

I suspect that the images that flash into the minds of many of us when we see the words ‘sustainability of wild species’ are of polar bears stranded on handkerchief-sized ice flows, tigers slaughtered for their skins and gallbladders, burnt koalas escaping bushfires or, more positively, whales breaching or vast herds of herbivores crossing African rivers and plains.

The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) – think UNFCCC for nature – has a much broader view of wild species, however. In their assessment of the sustainable use of wild species, IPBES defines:

- ‘wild species’ as any terrestrial or marine animal, plant or tree that hasn’t been domesticated or introduced and can live without human intervention, and

- ‘sustainable use’ as using components of biological diversity to contribute to human wellbeing in ways that do not lead to a decline of the diversity and that meet the needs of current and future generations.

IPBES recognises four ‘extractive’ practices (fishing, gathering, logging and harvesting) and one non-extractive practice (exemplified by nature-based tourism) for accessing wild species. They also identify nine categories of end use: ceremony, decoration, recreation, energy, food, medicines, materials, education and ‘other’.

Just as an indication of the scale of the use of wild species by humans:

- Globally, the use of wild species contributes daily to the wellbeing of billions of people through subsistence, income, culture and identity. Poor and rural populations in developing countries rely particularly heavily on wild species;

- Over 50,000 wild species are used, including 7,500 marine species, 7,500 trees, 24,000 other plants, 1,500 fungi and 7,500 amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals;

- 20% of the species used are consumed as food;

- Overexploitation is the main threat to wild species in marine ecosystems (a third of fish stocks are overfished) and the second biggest threat in terrestrial ones;

- Indigenous peoples manage the use of wild species on more than 38 million km2 (5 Australias) in 87 countries.

IPBES stresses the importance of recognising that many social as well as ecological factors influence, positively and negatively, the sustainable use of wild species. Interventions to promote sustainability must be tailored to local social and ecological contexts; ensure attention to fairness, rights of access, participation and equitable distribution of benefits; recognise Indigenous knowledge; and include robust but adaptive governance mechanisms that operate across levels of government and sectors and strengthen customary institutions and rules.

Collie’s Just Transition

You wouldn’t really know it in the eastern states but Western Australia has its own independent supply of electricity based in Collie, a town of about 7,000 people 200 km south of Perth. Collie has two coal mines and three coal-fired power stations, all publicly owned and all scheduled to be shut down by 2030.

Alan Kohler has had a look at how the state and local governments, the local community and businesses, and the unions are working together to ensure that the loss of Collie’s principal reason for existence for the last hundred years doesn’t result in the death of the town and the destruction of thousands of lives. Generally speaking, he likes what he sees:

- A Just Transition Working Group with four sub-committees, including one to celebrate Collie’s history and future;

- The leadership and involvement of Premier Mark McGowan;

- Regular open and honest communication with the community;

- Creation of jobs in the region – for instance, demolition and rehabilitation work on the mines and power stations, investment in renewable energy and tourism, and moving the state’s bushfire operations to Collie;

- An individual transition plan for each of the 1500 employees.

Kohler encourages the governments on the east coast to look to the west for inspiration on how to close down their coal industries responsibly.

‘Fortress conservation’ in Tanzania

A few weeks ago I highlighted the issue of ‘fortress conservation’, with reference in particular to the Democratic Republic of Congo. While one needs to be cautious about accepting everything at face value, there are also stories coming out of Tanzania about the government using force to evict 70,000 traditional Maasai owners from land bordering the Serengeti and Ngorongoro wildlife conservation areas. The government claims that the evictions are legal and necessary to avoid damage to the land resulting from the growing Maasai population. The Maasai and their supporters point to a court order that recognised the Maasai as the traditional owners of the land and claim that the government wants to hand the land over to a company from the United Arab Emirates that will turn it into a commercial game hunting reserve.

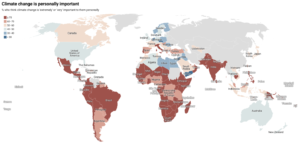

Climate change: what the world thinks

The vast majority of people in 81 surveyed countries think that climate change is happening. Only in Haiti and Laos (both 67%) were less than 70% of this view.

However, the percentage of people who feel that they know ‘a moderate amount’ or ‘a lot’ about climate change was much lower (72% of Australians were in these two categories). In some countries up to a third said they’d never heard of climate change.

In only about fifteen countries did more than half think that climate change is ‘mostly’ caused by humans – Australia 50%.

While majorities of people in most countries worry about the risks associated with climate change, people seem to think that the risks are far greater for their country as a whole and for future generations than for themselves. And somewhat puzzlingly, people in South America and Africa express low concerns about the risks of climate change to themselves but think it is ‘extremely’ or ‘very’ important to them personally.

The majority of people in most countries think that climate action should be a ‘very high’ or ‘high’ priority for their government (71% in Australia) but much lower percentages, particularly in Africa, the Middle East and South Asia think that their country should reduce its greenhouse gas emissions regardless of what other countries do (65% in Australia). That said, inhabitants of many African and South Asian countries express greater willingness to join community groups promoting climate action than inhabitants of the Americas, Europe and Australia. In Australia 6% are currently active in a group and a further 35% would definitely or probably be willing to join one.

All very interesting but it’s worth noting that the survey, conducted in March and April this year, was of 109,000 active Facebook users and I’m not sure how representative such people are of the general population.

Slow learners

The federal opposition seems to have missed the message that one of the reasons they lost the May election is that Australians are wanting strong action on climate change. NSW Liberal senator, Hollie Hughes, Shadow Assistant Minister for Climate Change, said on the ABC, ‘climate change is not Australia’s problem, it is not a regional problem. Our emissions are 1.3 per cent. We can shut everything down and we will make zero difference’. Old habits die hard.

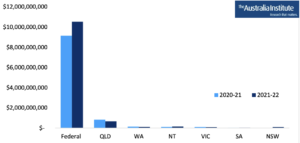

Fossil fuel subsidies

In 2021-22 Australian Federal and state governments provided $11.6 billion dollars of subsidies to fossil fuel industries in the form of spending (for instance on infrastructure such as ports, railways, pipelines and power stations) and tax breaks. This was a 12% increase on the previous year. The vast majority ($9.4 billion) was in the form of Federal tax concessions, of which the largest was the Fuel Tax Credits Scheme, a whopping $8 billion and projected to increase to $9.9 billion in 2024/25.