It does not matter much if Treasury forecasts of net overseas migration (NOM) from one year to the next are out by 30,000 or 40,000 as is likely for the 2019 Budget forecast for 2020. This happens regularly. But it is much more serious if forecasts are out by this much for every year over the four years of the forward estimates.

Over ten years, it becomes crucial. Over the 40 year timeframe of the Inter-Generational Report, it is a factor that drives just about everything from an economic and social perspective.

NOM is the difference between long-term and permanent arrivals and departures irrespective of citizenship or visa status. A NOM arrival is defined as a person who enters Australia and remains here for 12 out of the next 16 months. A NOM Departure is someone who has lived in Australia for at least that length of time and then leaves Australia for at least that length of time. NOM is the means by which the ABS estimates the contribution of immigration to Australia’s population.

It is because of our high rate of NOM over the past 20 years that Australia is now the youngest, most diverse and fastest growing major developed nation in the world. That has had both positive and negative impacts, with the negative impacts being largely due to poor government planning for the rapid rate of population growth it relied upon to deliver rapid economic growth.

This goes back to Treasury forecasts of NOM, both in the annual Budget and in the Inter-Generational Report.

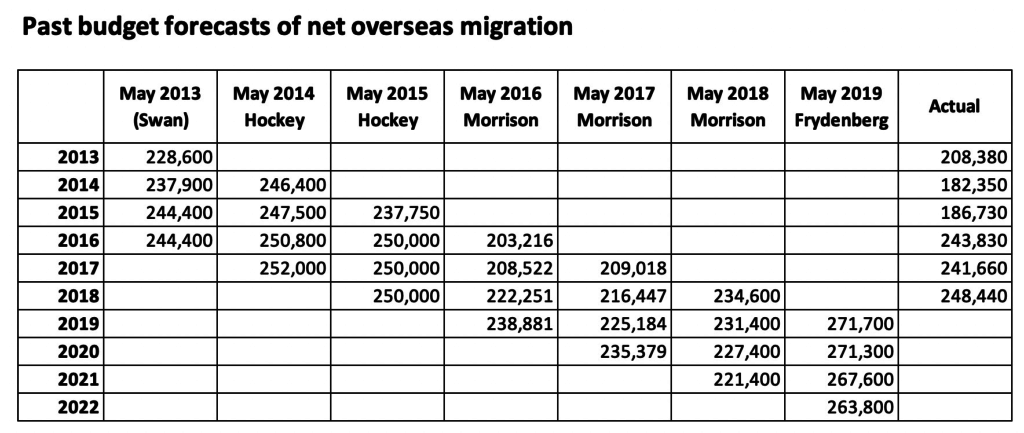

Treasury forecasts of NOM from one budget to the next change very rapidly (see Table 1). Yet little to no explanation is provided in the budget papers for these changes. In the 2019 Budget, Frydenberg dramatically reversed Morrison’s 2018 NOM forecasts despite Morrison’s announcement he had cut the permanent migration program. Yet Frydenberg provided zero explanation for the change.

While changes in NOM forecasts can partly be due to immigration policy changes, the fluctuations are just as much due to changes in relative economic conditions. When our economy is weak, as it was under Tony Abbott in 2013-14 and 2014-15, NOM fell below 200,000 per annum even though immigration policy was facilitative and the permanent migration program was being delivered at around 190,000 per annum. When our economy strengthens, as it did in 2016-18, NOM increased to almost 250,000.

That is why almost every Treasury forecast shows NOM rising in the outyears. Treasurers insist economic growth will progressively strengthen due to their far-sighted economic policies and Treasury knows this means NOM has to rise. The impact on per capita economic growth, however, is more complex.

For the 2019 Budget, there was the added pressure from Scott Morrison’s commitment to create 1.25 million jobs over five years – unless Morrison was expecting more people to take up two and three jobs each, the basic arithmetic means this requires a higher level of NOM given the rising number of retiring baby boomers and our already high participation rate. There was also the pressure to show the budget surplus rising during Frydenberg’s ten year plan to underpin his argument that government net debt would be repaid by 2030.

Hence in the 2019 Budget, Treasury forecast NOM rising strongly compared to the 2018 Budget when it forecast NOM to be steadily in decline – the only Budget in recent years to do so.

The difficulty for the general public is that Treasury rarely explains why its forecasts of NOM change from one budget to the next. Nor does Treasury explain any forecast changes to the composition of NOM. Compositional changes in terms of visa type can have a very significant economic, budgetary and social impact.

Even the Inter-Generational Reports provide very little explanation of the NOM forecasts used, either in terms of level or composition, despite NOM being a central driver of long-term economic and budget impact.

For the 2020 Inter-Generational Report, it is time the Treasurer took us into his confidence and explained his NOM forecast in detail. Hopefully the creation of a dedicated Population Unit in Treasury can help with that.

Abul Rizvi was a senior official in the Department of Immigration from the early 1990s to 2007 when he left as Deputy Secretary. He was awarded the Public Service Medal and the Centenary Medal for services to development and implementation of immigration policy, including in particular the reshaping of Australia’s intake to focus on skilled migration. He is currently doing a PhD on Australia’s immigration policies with a particular focus on forecasting NOM.