The Prime Minister says the coronavirus crisis will drive net overseas migration in 2020-21 down by 85% of its level for 2018-19. But what would net overseas migration average during the decade of the 2020s under current policy settings?

This is a critical question the Treasurer will need to address in the 2021 Intergenerational Report. Table 1 provides a forecast of net overseas migration for the decade of the 2020s assuming current policy settings are maintained for the whole decade.

Table 1: Forecast of Net Overseas Migration for Decade of 2020s

The above forecast of average net migration during the decade of the 2020s at 174,800 per annum assumes average real economic growth for most of the 2020s at around 2.3% per annum as per the forecast for the decade of the 2020s in the 2007 Intergenerational Report. It also assumes a weak labour market consistent with a significantly more aged population and a declining working age to population (WAP) ratio.

Net overseas migration during the past decade averaged 215,706 per annum compared to the forecast average net overseas migration in the 2019 Budget of 268,000 per annum. The 2019 Budget forecast for net overseas migration and fertility rising to 1.9 babies per woman was highly unrealistic, even before the coronavirus crisis.

Note that 2.3% real economic growth is still well above the average real economic growth across the OECD as a whole post-WAP peak. It is, however, well below the 3% average real economic growth assumed in the ten year plan published with the 2019 Budget.

The forecasts also assumes the overall migration program will be delivered at around 160,000 in most years with a one-third to two-third balance in favour of the skill stream (including onshore grants). Note net overseas migration in 2014-15 was 184,030 when we had an unemployment rate of 6% and a much larger migration program of 190,000. This highlights the impact of a weak labour market on net overseas migration.

It is also assumed that the Humanitarian Program will be delivered at the current level of around 18,000 with around 2,000 to 3,000 visa grants per annum to onshore asylum seekers.

Students (1)

The forecast assumes that the changes to student visa requirements made in September 2019 continue, particularly for the sub-continent, leading to reduced arrivals (around 10%-12% reduction on 2018-19) and a higher portion of departures due to fewer onshore stay opportunities. The forecast also assumes offshore student visa grants for Chinese Nationals will continue to decline with Australia’s deteriorating relations with China.

It is highly unlikely that additional offshore student visa grants from other source countries (eg Colombia) would be sufficient to offset the much stronger decline from Australia’s three major source countries for students (ie China, India and Nepal) in the nine months to end March 2019 (ie before the full impact of the coronavirus on offshore student applications).

The Australian Skills Quality Agency has taken some limited steps to tighten policy on private VET colleges that should also reduce demand.

Overall, this means substantial long-term shrinkage in Australian universities, VET providers, schools and associated businesses under current policy settings. Given the speed with which the industry had grown in the past 5-6 years, some decline was inevitable even without the coronavirus crisis.

But this will mean that areas of Australia’s major capital cities where most overseas students live, study and work will be severely impacted, limiting recovery in the surrounding areas even after international borders are opened.

Skilled Temporary Entry (2)

The forecast assumes the tightened skilled temporary entry policy introduced in 2017-18 continues and the decline in the number of people in this category in Australia that started from 2013-14 also continues. That will be exacerbated by a weaker economy and labour market, noting that this category is the most sensitive to fluctuations in the economy.

While this category recovered strongly after the GFC, that appears unlikely after the coronavirus crisis given the very different design of these visas since 2017-18.

Visitors (3)

The assumption is that the rapid increase in the contribution of visitors to net overseas migration over the past 5-6 years due to Australia’s fifth and largest wave of asylum seekers (mostly unsuccessful) is brought under some greater control. The risk is that the control measures are poorly targeted. That would have a highly negative impact on Australia’s tourism industry and may also result in refoulement of genuine refugees.

The extent to which visitors are applying after arrival for other visas, particularly partner visas, is likely to continue given the growing size of the partner backlog.

Working Holiday Makers (4)

Assumes the decline in the stock of WHMs ceases and remains around the level for 2018-19. That would allow for some further decline in the sub-class 417 visa (working holiday makers) and an increase in sub-class 462 (work and holiday visa) as country caps on these are progressively raised.

The successful legal challenge to the so-called ‘backpacker tax’ and the addition of a third year on a WHM visa may enable some re-growth in WHMs but this would be offset by the weak labour market, on-going social media reports of exploitation and tightening of pathways for WHMs to extend stay on other visas after arrival.

There is also some question around whether demand for sub-class 462 from China would remain strong given current diplomatic tensions.

The other potential impact on WHM numbers include:

- successful measures to reduce abuse of the asylum system for labour hire companies to deliver cheap labour to farmers in particular – this would increase demand for WHMs; and

- possible introduction of an agricultural visa along the lines of that in the USA thus reducing demand for WHMs.

Other Temporary Entrants (5)

There are likely to be three key drivers in this grouping:

Firstly, a steady increase in the new temporary parent visa category which has a cap of 15,000 visas per annum. In the longer-term, a key issue with this category will be whether many of the temporary parents are willing to leave Australia after their five year visas expire. There will also be issues around cost of health and aged care as private insurance may only cover part of these costs.

Secondly, there are now over 100,000 temporary graduates in Australia. This number will continue to rise for a number of years as overseas students complete their courses and secure this post-study visa. But as pathways for temporary graduates to extend stay and/or secure permanent residence have been severely limited, departures on this visa will rise especially with a weak labour market.

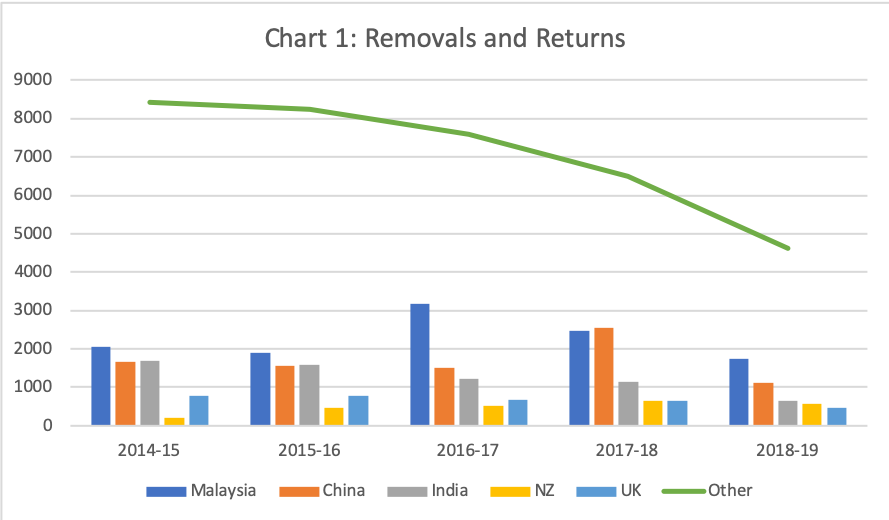

Finally, we may also see an increase in departures of unsuccessful asylum seekers who are unable to keep working due to no work rights (ie DHA and AAT start to get on top of the asylum seeker backlog) and a weak labour market. A key issue here will be whether DHA will move to increase removal and return of failed asylum seekers or continue to give this function a low priority so as not to upset farmers and other employers who rely on asylum seekers for cheap labour (see Chart 1 highlights a steady decline in overall removals and returns despite the surge in unsuccessful asylum seekers).

Permanent Family (6)

The key to this category is how the Government manages the growing backlog of partner visas which is now over 100,000 when cases at the AAT are included. With limited places available compared to the application rate, the backlog will continue to grow.

Part of the onshore backlog may be cleared while international borders are closed. This will be limited, however, because of the Government’s reluctance to abandon the two-thirds skill stream versus one-third family stream policy.

An increasing number of partners who are living overseas will seek to avoid the long wait to be re-united with Australian partners in Australia by entering Australia on visitor visas and then applying onshore. Alternatively, more couples may choose to live in another country in order to be together.

The Government’s (most likely unlawful) limit on partner visas may come undone if there is a successful legal challenge to its management of partners. That would increase permanent family arrivals.

Permanent Skilled (7)

The forecast assumes the Government will maintain its current historically very small number of places in the Skilled Independent category (SC 189) – other than for NZ citizens who are already in Australia. This category is disproportionately drawn from people who are overseas and hence contributes more to permanent skilled arrivals.

Current policy is to rely mainly on State/Territory governments to sponsor migrants predominantly from those already in Australia (thus not adding directly to net migration). But this also carries substantial long-term risks.

The new Global Talent Independent visa is designed to add to Australia’s talent pool. Indications are, however, that this visa may effectively become a replacement for employer sponsorships and be driven largely by people already in Australia.

Humanitarian and Special Eligibility (8)

The forecast assumes Government maintains the Humanitarian Program at around current levels with around 2,000 to 3,000 successful onshore asylum seekers each year securing permanent residence.

Permanent Other (9)

This category is largely for existing Australian permanent residents who leave Australia for more than 12 months on a Resident Return visa.

The forecast assumes the current rate of Resident Return movements is maintained.

New Zealand Citizens (10)

The movement of New Zealand citizens is largely driven by the relative state of the two labour markets. Since around 2013-14, New Zealand’s unemployment rate has been around one percentage point lower than Australia’s and hence net movement of New Zealand citizens to Australia has been relatively low.

The forecast assumes NZ economy and Australian economy and labour market are both relatively weak with the relativities of recent years maintained.

Australian Citizens (11)

The forecast assumes rate of Australian citizen movements of past 5 years is maintained noting that Australia’s relatively weak economy from around the time of the Abbott Government led to a sharp increase in the net number of Australian citizens leaving Australia.

Impact on Australia’s Population Directions

Net migration averaging around 175,000 per annum plus a fertility rate of around 1.65 babies per woman, would result in Australia’s projected population growth rate falling sharply compared to that assumed in the 2019 ten year plan.

It would also lead to a sharp acceleration in population ageing.