RBA Governor Philip Lowe’s speech last week on the Labour Market and Monetary Policy set off a frenzied debate on the impact of immigration on wages.

He noted the RBA’s forecast of “wages growth was persistently lower than forecast…but employment growth has mostly been in line with, or exceeded, expectations”.

Lowe listed a range of factors in the growth of the labour force including rising female participation and participation of both males and females aged 55+, partly due to more flexible working arrangements and availability of child care.

But the point that stimulated the most debate was Lowe’s reference to firms hiring overseas workers “to overcome bottlenecks and fill specific gaps where workers are in short supply. This hiring dilutes the upward pressure on wages in these hotspots and it is possible that there are spillovers to the rest of the labour market”.

Lowe was interpreted as suggesting this is somehow a new phenomenon or unique to Australia.

It is not.

Australian employers have been able to recruit skilled workers directly from overseas for over 30 years through what are known as skilled temporary entry visas – the former Sub-Class 457 and now labelled Sub-Class 482.

Employers in every major developed economy have this option available to them. In the US, for example, these visas are known as H1B.

Lowe also did not mention that since 2012, when wage growth was a more acceptable 4 per cent and has not reached that level since, there has actually been a significant fall in skilled temporary entrants contributing to net overseas migration from 32,520 in 2012 to 8,810 in 2014 and remaining at around this level.

Lowe’s hypothesis that skilled temporary entry dampens wage growth, at least in higher-paid jobs, is not supported by the experience from 2012 until today.

More significantly, the RBA Governor failed to examine how immigration levels and composition have actually been impacting the Australian labour market since wage growth fell from around 4 per cent in 2012 to around 2 per cent in 2016 and hovering around that level until 2020 when it fell even further.

Net Overseas Migration Since 2012

Net overseas migration measures the net long-term and permanent movement of all people into and out of Australia, irrespective of citizenship or visa category.

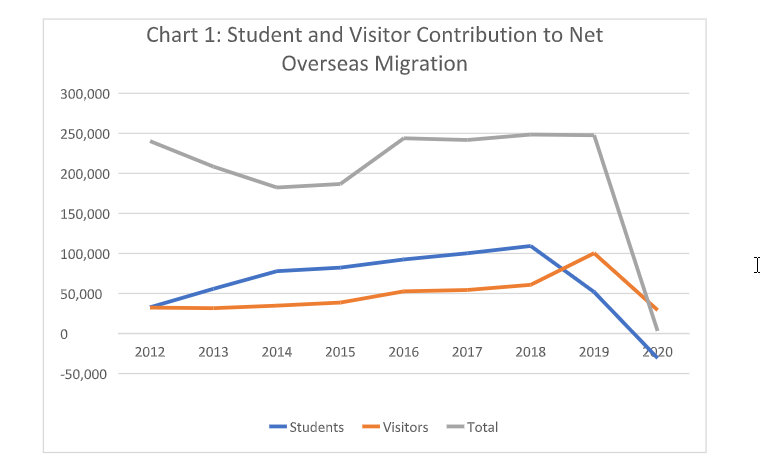

In 2012, net overseas migration was 240,250 having increased from 206,240 the year before. It fell to 208,280 in 2013 and fell further to 182,350 in 2014 (see Chart 1). This decline was despite the permanent migration program, that is the total number of permanent non-humanitarian visas issued, remaining at 190,000 per annum in those years.

The sharp decline in net overseas in 2014 was due to a remarkable increase in the net outflow of Australian citizens from negative 6,540 in 2012 to negative 22,410 in 2014; a reduction in net arrival of New Zealand citizens from 42,050 in 2012 to 7,390 in 2014 and a fall in skilled temporary entrants.

This was a response to a significant increase in unemployment to over 6 per cent and a fall in unemployment in New Zealand. Net overseas migration to Australia has always tracked the state of the labour market.

The deterioration in the labour market in Australia in 2014-15 was also accompanied by a decline in wage growth that has persisted to this day.

Chart 1 highlights the strong increase in the contribution of students to net overseas migration from 2012 until 2018 when it contributed around 44 per cent of net overseas migration.

The second-largest increase in contribution has been from visitors changing status after arrival which peaked at an astonishing 100,000 in 2019.

While there is little publicly available data on what visas these visitors are applying for, we know there has been a major increase in visitors applying for asylum over the past 6-7 years in the biggest labour trafficking scam in Australia’s history which this website has been reporting on for over three years.

The scam is predominantly aimed at supplying low paid farm labour. Even in 2021 with international borders largely closed, the Department continues to receive around 800 to 1,000 onshore asylum applications per month.

Another major development in Australia’s labour market that Lowe did not mention is the extraordinary increase in the number of retirees in Australia. Between 2008-09, when Australia’s working age to population ratio peaked, to 2018-19, Australia experienced the biggest increase in its retiree population on record.

Because most of these people would have been on or near the highest salaries in their lifetimes, their departure from the labour market would have had a substantial impact on the overall wage bill.

In other words, since 2012, we have seen large numbers of high-income earners leave the labour market or leave Australia as well as a decline in the number of higher-paid immigrants while there has been a major increase in the number of lower-paid and often heavily exploited students and asylum seekers.

This trend is likely to continue as the number of retirees continues to rise strongly over the next decade or two, the Government has expanded work rights for students to make them an even more important part of the labour market and announced a new Agriculture Visa but proposes to do nothing about the labour trafficking scam for farm work.

Of course, this is in addition to the Government’s ongoing policies to put downward pressure on wages which Lowe did not mention at all.

Policies such as caps on public sector wages; cutting of penalty rates; industrial relations reforms to strengthen the hand of employers in wage bargaining leading to some 700,000 fewer workers being covered by Enterprise Agreements since 2013; increased casualisation of the workforce; keeping a lid on minimum wages; and the Government continuing to largely ignore rampant wage theft by underfunding the Fair Work Ombudsman and maintaining very weak penalties for wage theft.

The RBA Governor may have to lament weak wage growth in Australia for some time yet, especially as weak wage growth appears to be strongly associated with an ageing population and weak growth in private consumption expenditure.