Suppressing the virus will require much lower caseloads before lockdowns can lift, even if we meet vaccination targets.

The Morrison government insists that present lockdown restrictions will be substantially eased when 70 per cent of the adult population is vaccinated and then removed at 80 per cent. But continuing suppression of the virus will also require much lower caseloads before governments open up.

No one likes lockdowns. They damage our sense of well-being and the economy. However, the present lockdowns are there for a purpose. Without these lockdowns the spread of the virus would have been much worse.

In the UK, for example, with more than twice the Australian vaccination rate, their Covid caseload since they lifted all restrictions has escalated to 13.5 times higher than the Australian rate as a proportion of the population, while the UK death rate is 50 times higher.

The critical question therefore is when will it be safe to remove the present lockdowns, and what other measures might still be required?

The Morrison government has focussed almost exclusively on vaccinations as representing the way back to normality. To this end the government commissioned the Doherty Institute to model future caseloads after 70 and 80 per cent vaccination targets have been achieved.

Based on this modelling, at the end of July, the national cabinet agreed in principle that when 70 per cent of the adult population in both Australia and a state have been fully vaccinated then the state would ease its restrictions, especially for vaccinated people, and lockdowns would be less likely but possible.

Then when 80 per cent of the adult population were vaccinated in both Australia and the relevant state, minimum baseline restrictions might remain, but vaccinated Australians would be freed from all restrictions, and only highly targeted lockdowns would be allowed.

In the month or so since this national plan was released, however numerous critics, including some state premiers, have expressed concern that these targets only refer to the adult population and ignore children under the age of 16. This means that a vaccination target of 80 per cent of the population aged 16 and over, is effectively a target of only 64 per cent of the total population.

These critics have understandably asked whether this is sufficient, or should we aim to vaccinate more children before lifting restrictions? Alternatively, if that is not possible, should the vaccination targets for easing restrictions be increased from 70 and 80 per cent of the adult population to something more?

These are both legitimate questions, but there is another even more important concern about the present vaccination targets for reducing restrictions.

The problem is that although the vaccination targets in the national plan purport to be based on the Doherty model, in fact these targets effectively ignore a critical assumption in the Doherty modelling, which is the capacity of the state health systems to test, trace, isolate, and quarantine (TTIQ) new infections effectively.

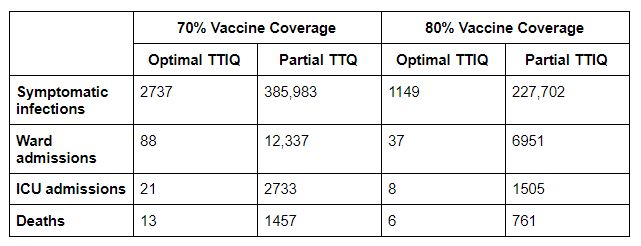

The Doherty Institute therefore modelled two alternative scenarios:

- An “optimal” TTIQ response, which it deemed achievable when the active case numbers can be contained in the order of 10s or 100s;

- A “partial” TTIQ response, deemed more likely when established community transmission leads to rapid escalation of caseloads in the 1000s and beyond.

The difference between these two scenarios at 70 and 80 per cent vaccination coverage is shown in Table 1 below, which is taken from the Doherty report. What stands out is the huge difference between the number of infections, hospital and ICU admissions, and deaths, with partial TTIQ compared to optimal TTIQ.

Table 1. Comparison of cumulative outcomes over the first 180 days with optimal and partial TTIQ and nominated vaccine coverage achieved prior to transmission

For example, with only the lowest-level baseline restrictions and partial TTIQ, the projected number of deaths from Covid are as many as 1457 and 761 deaths with 70 and 80 per cent vaccine coverage respectively. On the other hand, with optimal TTIQ the deaths would be as low as 13 and 6 respectively. That is a huge difference.

Equally the number of hospital ward admissions with only partial TTIQ, may mean that the hospital system cannot cope. While with only low-level restrictions and partial TTIQ, the number of infections would be so high that the transmission rate (or effective reproduction rate) may well be significantly higher than 1 and the pandemic would be out of control.

This is why the Doherty report, itself, highlighted: “the importance of maintaining optimal TTIQ responses in the context of ongoing ‘low’ public health and social measures to minimise epidemic growth and escalation of severe disease outcomes, even in a highly immunised population”.

What determines the difference between optimal and partial TTIQ is therefore critically important. That in turn is mainly determined by the size of the caseload, and especially the number of people who have been infectious in the community. Indeed, the Doherty report specifically noted that “the TTIQ public health response will be less effective at high caseloads” (something of an understatement given the difference it makes).

In short, the size of existing caseloads can result in huge differences in the number of Covid infections, hospitalisation, and deaths, irrespective of the extent of the vaccine coverage.

The national plan, however, presumed that by the time the 80 per cent vaccination target was reached, then the virus would have been suppressed, with no or at most very few cases. In that case, the health and TTIQ systems could cope, and the restrictions would not be needed.

But the recent outbreaks of Covid in NSW, Victoria, and perhaps the ACT, have thrown this assumption away, at least for the time being.

Instead, practical experience reinforces that there are in fact two key variables, not one, which should determine when restrictions are lifted. Certainly the proportion of the population that is vaccinated is important, but so too is the effectiveness of the TTIQ system and this depends upon the number of Covid cases, especially the number which were infectious in the community.

The extent to which restrictions are relaxed should therefore also be based on the caseload at that time and confident predictions that it will fall further. If the authorities get this wrong, they will very likely find that the number of deaths is unacceptable, and the hospital system is overwhelmed.

So in considering when to ease restrictions, governments need to not only set a vaccination target but also consider:

- what number of daily cases can we live with, taking account of the inevitable strain on the hospitals and the deaths that will occur, and

- what restrictions on mobility will need to be retained and for how long to achieve this target.

It is one thing to argue that we must accept that we cannot get back to zero Covid cases before we relax restrictions. But we need to consider the strain on the hospitals, and the deaths that will occur, before determining the target caseloads for progressively easing restrictions.

Unfortunately, the Morrison government has ignored this other key variable in the Doherty modelling – that the number of cases does affect the effectiveness of the TTIQ system and should therefore affect the decision as to when we can relax restrictions and open up.

NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian is equally determined to begin opening up when NSW achieves its target of 70 per cent fully vaccinated in October. But that is when case numbers are also expected to peak, along with a peak hospital load at the same time.

So nothing could be more risky. The premier is busy creating an expectation that considerable freedoms will be returned in October, but with a high probability that the then very high number of infections will blow out further, thus overwhelming the TTIQ system and the health system more generally. In that case, the only course will be a return to a tight lockdown, but possibly affecting more regions.

A revised national plan is needed for when we can progressively remove the restrictions and end the lockdown. This plan should acknowledge that a vaccination target alone is insufficient. The impact of the number of infectious cases on the capacity of the TTIQ system is equally important.

Targets should therefore be set for both vaccinations and the number of infectious cases which will together determine the easing of restrictions and the ending of lockdowns.