Bruce Haigh, who died on April 7, was a diplomat, an adventurer, an artist and writer, a humanist, a romantic and a man with a deep love of his country, who mourned its fading ideals and values.

Ominously, Bruce was born in Sydney on 6 August, 1945, the day the Americans dropped the atom bomb on Hiroshima. Growing up in Newcastle and Melbourne, his family moved to Perth, then an isolated city built on sand.

There, he was educated at Christ Church Grammar School, which laid a firm foundation for his rebellious streak. “The ethos of the school was to instil a compliant and a conservative view of the world,” Bruce once said. Beatings were frequent and violent, he remembered “A significant power imbalance was exploited leading to long and lasting anger at enforced degradation.”

Bruce was to carry that passion, anger and resentment of unjust authority with him for life, often getting into hot water by standing up for various underdogs, usually to the detriment of his own career. “We were in an ideological hot house of conservative political, social and religious ‘values’, packaged in stultifying mediocrity and prejudice,” he reflected on his youth in WA.

Seeking escape, he one day strolled into the head office of the Pastoralists and Graziers Association, lied about his ability to ride a horse and was despatched to jackaroo in the Kimberley. It was the days when jackeroos were paid a pittance, but were expected to dress for dinner with the Station owners. Bruce loved it.

Here he witnessed the ‘other side’ of Australia. “There were black people speaking another language, they were easy with each other, they were in a majority, I felt I was in different country. I was. The Kimberly was different, strange and beautiful. I felt lost and excited.” He was also angered by the racism and distressed by the loss of Aboriginal culture. It was in the Kimberley that his love for Australia, its nature and its essential values flowered.

“The billabong was a haven for bird life; magpie geese, ducks, cockatoos, budgerigars, early rising brolgas, parrots – and pelicans, who took off early to avoid the heat, lazily riding the thermals all day, descending in the evening to feed. Spectacular thunderstorms played around us, marking the horizon. Distant bushfires were left to burn out.”

The Vietnam war broke out and Australia fell over itself to join in. Despite not being entitled to vote, drink or get a bank loan, Bruce found himself conscripted to drive tanks for the Army. He freely admitted, at the time ”I had no objection to the war in Vietnam and conscription; on the contrary, I was of the belief if the government said it was necessary, that was reason enough. I presumed they had a depth of knowledge greater than mine. Few of my fellow ‘Nashos’ were equipped to question, so we complied. We were cannon fodder.” These were views he would subsequently disavow.

National service was followed by an Elysian period studying political science under the redoubtable Paddy O’Brien, at the University of WA. Bruce boarded at St George’s College, studied hard, played hard and pursued sundry ladies. He was chosen as the College’s Senior Student. “A top night out was dinner at the Adelphi Steak House with a bottle of red wine. The Rolling Stones were still not getting any satisfaction – which wasn’t the case for us – and we danced to “Hey, you, get offa my cloud.”

In keeping with his emerging Renaissance character, Bruce took to oil painting, executing some remarkable Australian landscapes with a palette knife. In later life he sponsored the careers of many young artists, especially in developing countries.

In 1972, breathing a sense of high adventure, he joined the Commonwealth Department of Foreign Affairs. Bruce was only a few weeks into his training when “after suffering pompous and dull public servants and academics for some weeks it started to dawn on me that we had not been collected together to learn – but to be institutionalised.” His initial take on DFA was “It was Dickensian! It was almost as if people were sitting on high stools writing with quill pens and that was frustrating.”

It was an ominous insight and Bruce was glad to get an initial posting to Pakistan, where he recalled “The Australian missions in Islamabad and New Delhi were at war with one another, prosecuting the merits of the recent conflict and its aftermath on behalf of their host countries.”

With his nose for politics, Bruce scented trouble brewing in neighbouring Afghanistan and, with Ambassadorial blessing, piloted the Embassy’s Holden Kingswood up the Khyber Pass to see (and photograph) what the Soviets were up to as they schemed their invasion.

As a diplomat he spent years in ‘hardship postings’ in some of the world’s trouble spots where his nose for local politics frequently led him into collision with the more conservative elements of his own department. Bruce was outspoken in defence of the wronged and the downtrodden and didn’t mind who knew it. He was also shrewd in reading the shifts in the local political wind, long before they were recognised officially.

In 1976 he flew into apartheid South Africa, then a police state in the grip of a student uprising in which 700 protestors died during its early weeks. ”Apartheid was laid out below. Cramped, drab and draped in coal smoke, the narrow streets and small box houses of the African townships stood in marked contrast to the pool-studded mansions,” he recalled. Bruce found himself immediately engulfed in black artists, activists, trade unionists, journalists and defence lawyers, all eager for change. He began to build a wide network among the dissidents.

“After a week or so, I realised I had been posted to a dysfunctional Embassy in a dysfunctional country. Senior Australian diplomats seemed to meekly accept the regime’s word, that the protests were staged by ‘criminal gangs and communists’.” He soon crossed swords with his Ambassador – over the plight of detained YWCA workers – who tried to get rid of him.

Unbowed, Bruce continued to work to have Australia grasp the true situation. “My commitment in fighting Apartheid was strong – but the emotional toll was high,” he admitted. The country was exploding.

He befriended the legendary newspaper editor Donald Woods, an outspoken critic of the regime. Through Woods he met Desmond Tutu and became a close contact of leading dissident, Steve Biko, before he was detained: “He was a natural leader. Tall, good looking, highly intelligent. He just had that indefinable and yet very strong presence of leadership. If he’d lived, I think he would have been the leader of South Africa.” But, Bruce says, “Within three weeks of being detained Steve was dead, beaten by police whilst handcuffed.”

With Woods, he attended Biko’s funeral, a vast gathering to the strains of “Nkosi Sikelele iAfrika”, reporting it as a turning point in relations between blacks and whites in South Africa.

Woods was arrested trying to leave the country, banned from publishing and placed under home detention. A poisoned T-shirt was send to his infant daughter. He decided to fly the country – and asked Bruce for help. “In theory my diplomatic immunity gave me the ability to take Donald out of the country but at risk to both of us because there was no guarantee that the regime would respect that immunity.” In the end, with Woods disguised as a priest, Bruce drove him across the border into Lesotho, floored the accelerator to evade pursuit and made it to the British High Commission three hours later. Outside South Africa, Woods became a prominent world voice for anti-apartheid – and Bruce found himself depicted in the Attenborough movie ‘Cry Freedom’. “The Australian Government had no idea of my role in helping Donald and his family escape South Africa. To protect my identity I was portrayed as an Australian journalist.” He continued to work with and run dissidents over the frontier.

But the SA Bureau of State Security (BOSS) was watching. Their next move was an attempt to smear Bruce in newspaper articles claiming he was having an affair with a female black activist because he had been seen in pyjamas at her home – sex between the races then being outlawed. Bruce returned serve through his extensive media contacts, explaining he never wore pyjamas!

Posted to Pakistan again and reading the writing on the wall for its corrupt regime, he befriended Benazir Bhutto, the Oxford-educated daughter of the murdered Sheikh Bhutto, on her destined path to become the first woman leader of a Moslem nation. One of her first acts on becoming President was to call Bruce and ask him to arrange a major delivery of Australian wheat to ease the starvation that was gripping the country at the time.

Posted to Saudi Arabia, Bruce organised the rescue of an Australian nurse who had been sentenced to a flogging – 90 strokes of the cane – for drunken driving. Bruce, his sense of chivalry aroused, called on the Saudi Foreign Ministry where he carefully explained that the world outcry over “Death of A Princess” would be nothing compared to what would follow the lashing of a western woman. Also, he pointed out, the Saudi Ambassador to Australia’s son had recently been arrested for drunken driving in Canberra… The nurse was quietly released and left the country.

In 1984 he was appointed head of the Indonesia section in Foreign Affairs, where his sense of injustice was inflamed by the Indonesians’ treatment of the East Timorese: “I thought the invasion was a travesty of fairness and human rights; it appalled me when Australia acquiesced.” He was also infuriated by the Australian Government’s studied indifference to the murder of five of our journalists at Balibo, disclosed in a secret investigation – and later, after leaving Foreign Affairs, helped to expose the truth. “The report (by an Australian investigation team) concluded that the newsmen had been shot, the bodies burnt and the bones crushed in order to avoid identification,” he wrote in the Sydney Morning Herald in 1996. DFAT responded “to our knowledge”, there had not been any photographs of human remains taken by the Australian team in 1976. Documents subsequently released in 1999 were carefully sanitised, according to Bruce.

After another controversial posting in Sri Lanka, Bruce resigned from DFAT and in September 1995 was appointed a Member of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT), a post that engaged his humanity to the full: “People’s lives and often that of their families were in your hands. Some applicants wept, some shook, all were tense. I had one applicant curl up on the hearing room floor in a foetal position sobbing.” He was once more fighting for the underdog, in a country that was coming to have a vicious disregard of the downtrodden and oppressed. “Many hearings were sad and fraught, none more so than girls who had been trafficked to Australia from Asia for the sex trade,” he said.

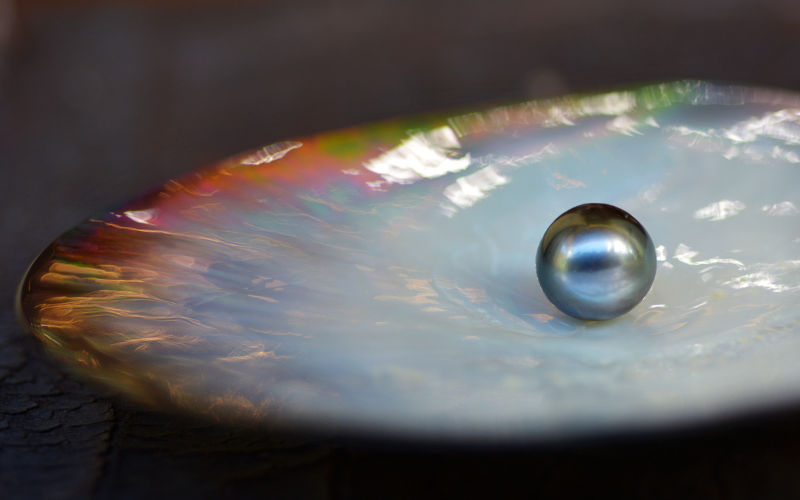

Following his stint on the Tribunal, Bruce fulfilled two lifetime’s ambitions – to become a farmer, growing olives and grapes at Mudgee, and to offer himself as an outspoken commentator and public intellectual on Australia’s frequent missteps in the treacherous minefield of diplomacy. His taught, acerbic and insightful analysis illuminated the columns of the daily newspapers, the ABC’s The Drum program, the radio airwaves and the august pages of Pearls and Irritations. Whenever he thought his country was making an ass of itself by misconstruing the situation or picking the wrong side, Bruce spoke up, to the fury and annoyance of many a politician and conservative media columnist. He feared deeply Australia becoming a ‘vassal state’ to the US, to be sucked again and again into that country’s interminable conflicts.

Bruce Haigh was married to Libby, with whom he had two sons, Angus and Robbie, and later to Jodie with whom he had two daughters, Sammie and Georgie. The premature death of his eldest son Angus, a marathon runner, in 2016 was a shattering blow, especially as it was soon followed by the loss of his farm and a harrowing operation for prostate cancer. Bloodied but unbowed, Bruce picked himself up, seeking health, discourse, distraction and fresh adventure in the company of his many friends and in travels to the Philippines, Vietnam and Laos – where his health problems finally caught up with him.

Bruce was loyal to the traditional Australian virtues of decency, mateship, candour and fair dealing – and fought all his life to uphold them against the dark forces that would corrupt or rob us of them. His memory and example will long outlive him.

You might like to view Bruce’s articles on Pearls and Irritations.

Postscript: Bruce’s good friend Allan Behm is seeking expressions of interest from readers of Pearls and Irritations and friends and admirers of Bruce for a memorial event, to be organised a month or so from now. allan@australiainstitute.org.au