China is not the urgent threat; climate change is

Oct 22, 2020Spending priorities by the federal government are increasingly questionable, if not indefensible; they raise fundamental questions about the competence and intelligence of our policymaking elites.

Australian security policy generally, and the saga about replacing the nation’s submarines in particular, highlight all that is short-sighted and misguided about the priorities of Australian policymakers. Brian Toohey’s recent forensic analysis of strategic thinking and defence spending details the astoundingly costly errors of planning and basic due diligence that will saddle long-suffering taxpayers with an unnecessary burden for decades.

The repeated basic policy failures and cost overruns by the defence department exemplify wider problems in the priorities and thinking of strategic and policy elites in the Canberra bubble. Not only are the new submarines — when/if they arrive and actually work — certain to fail in the primary strategic purpose of deterring China, but far more important, immediate and real threats won’t be addressed as a consequence.

If the People’s Republic of China isn’t deterred by the vastly superior military capabilities of the United States, it’s hardly going to be intimidated by anything Australia does, with or without its increasingly erratic alliance partner. But while we are endlessly demonstrating our reliability and strategic credibility by investing in costly (and unproven) new weapons systems, we will not have the resources to address more urgent threats to our national security.

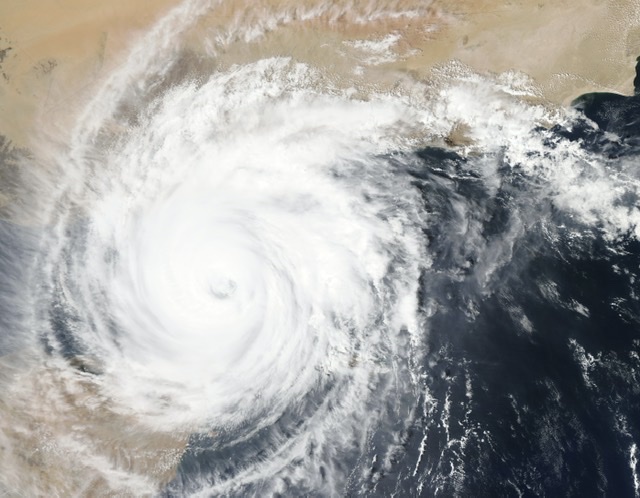

I refer, of course, to climate change, an immediate, rapidly intensifying problem that directly affects Australia, the driest continent on the planet. Environmental degradation and global warming not only potentially undermine Australia’s economic position, but also threatens the lives and livelihoods of the population.

The standard defence of this irresponsible and short-sighted policy is that Australia can make little difference to the trajectory of climate change if the likes of China, the US and India are not on board. Perhaps so, but it is striking that the same logic is not applied to defence acquisitions that are also incapable of making a decisive, independent difference to strategic outcomes in the Indo-Pacific region.

Paradoxically, Australia’s defence priorities actually demonstrate that the government is capable of long-term thinking and planning, but only in a limited number of areas. It will be 40 years until the submarine fleet is finally complete, by which time the world will be a very different place. If only some of the predictions made about the likely impact of global warming come to pass, there is a very good chance that future governments will be trying to deal with the impact of a 3°C rise in average temperatures, with all its catastrophic implications for human beings and the natural environment upon which they ultimately depend.

As Greg Jericho pointed out recently in the Guardian, by the time Scott Morrison’s youngest child reaches her father’s age, a 3°C temperature rise is as certain as anything can be about as complex an issue as climate change. The question is whether Morrison actually understands this and what it will mean for his immediate family, or whether he really believes Australia will remain magically — even divinely, perhaps — immune to the demonstrable impact of unmitigated climate change.

Some will consider this a cheap shot, no doubt, but given the stakes and the long-term affects of poor policy, it is reasonable to question the capacity of our leaders to actually understand what is happening. It is increasingly apparent what a danger Trump’s bottomless ignorance and self-regard poses to both his own country and the rest of the world.

Morrison’s background as a salesman may render him similarly incapable of recognising that the current global economic system is part of the problem and something that will have to be managed differently if we are to continue to enjoy our remarkably privileged lifestyles. Spending money we don’t have on weapons systems we don’t need — and which probably won’t work as advertised anyway — means we can’t tackle far more pressing and implacable problems that threaten to overturn the fabled ‘Australian way of life’.

It may actually mean thinking about how we encourage international cooperation of a sort that will potentially allow us to address some of the global problems we face. This will undoubtedly involve cooperating with, rather than trying to contain, China. It will also involve thinking more creatively about tackling issues of international inequality, and the possible moral obligations the West owes to the Rest.

We might hope that such a prominent Christian as Morrison might be keen on this in principle, at least. I think not. On the contrary, not only is Morrison seemingly incapable of putting any interest above his own, the Coalition’s and the nation’s (in that order), but he seems entirely indifferent to the fate of others not fortunate enough to enjoy our entirely arbitrary community of fate. With such complacent, incompetent and insular leadership, why are we surprised that so many of the young despair?