A regular collection of links to writings and broadcasts in other media

ABC’s Saturday Extra with Geraldine Doogue (from 0730 to 0900 or on their website in case you miss it).

How to help: as bushfires burn, people are wondering how best to donate time, money or resources. Geraldine talks to the Salvation Army’s Lyn Edge who has some good tips from the frontline.

That was the year, this was the decade: it’s the end of an era – The Economist’s Daniel Franklin and the Lowy Institute’s Michael Fullilove join us to discuss what we have learned.

Australia Calling – international broadcasting began as a propaganda arm – then morphed into a showcase for independent voices. 80 years after it started, do we still need it – and why? Geraldine is joined by an expert panel who weigh in on international broadcasting’s past, present and future. (One hour)

Other commentary

What emerges once neoliberal capitalism collapses – weak fascism?

It’s unfortunate that Marxists have developed their own economic and political vocabulary, because while their jargon eases communication among their colleagues, it tends to obscure their work from wider readership.

In the Monthly Review is an article Neoliberal capitalism at a dead end, by Marxist economists Utsa and Prabhat Patnaik. It’s not an easy read, and it starts on a strange tangent, but it soon gets down to the problems of contemporary capitalism – overproduction and asset bubbles. That’s essentially the same diagnosis as is made by our Reserve Bank Governor, but in Marxist language.

They don’t stop at analysis. They move on to consider the consequences when neoliberal capitalism reaches a dead end. Perhaps the traditional Marxist would expect them to forecast a revolution and new world order, but their prognosis is less exciting and somewhat more dismal. They acknowledge that while conventional social-democratic policies could rescue capitalism from its own destruction, such a pragmatic path would almost certainly be blocked by “the imperialism of international finance capital”.

They avoid any puerile assertion that capitalism and fascism are bedfellows, but they suggest that the economic failure of capitalism sets the conditions for fascism to arise. That won’t be the all-encompassing fascism of the twentieth century, which took hold because of unique conditions of the time, but it will be an ongoing force in states with weakened democracies.

Two observations on capitalism – from the workplace and from the academy

Bernard Keane in his Side View has drawn attention to a review in the New Republic. Life under the algorithm: how a restless speedup is reshaping the working class is Gabriel Winant’s review of two recently-published books: On the clock: what low-wage work did to me and how it drives America insane by Emily Guendelsberger, and Mongrel firebugs and men of property: capitalism and class conflict in American history by Steve Fraser.

Guendelsberger is a journalist who worked undercover in low-wage jobs in Amazon, Convergys (a call centre) and McDonald’s. It’s an account of the relentless and maddening pressure of twenty-first century Taylorism (with many more measuring devices than Taylor’s stopwatch.) Fraser, a labour historian, compares capitalism of the Gilded Age, which gave rise to countervailing union power, to capitalism of today, which operates on the omnipresent threat of unemployment and exclusion, thwarting the development pf any countervailing power. Traditional Taylorism, brutal as it was, incorporated the idea that the worker would share in the benefits of improved productivity. Even that bargain has been abandoned.

What is the purpose of a company?

If you search the Web (or go to the Westpac AGM) you will find plenty of voices critical of current corporate behaviour, with statements about what corporations should do. We might read that a company should “treat its people with dignity and respect”, “strive for continuous improvements in working conditions and employee well-being”, “have zero tolerance for corruption”, “integrate respect for human rights into the entire supply chain”, “pay its fair share of taxes”, “protect our biosphere and champions a circular, shared and regenerative economy”.

You might wonder where these quotes come from. It’s a fair guess that they don’t come from anyone in the present Commonwealth Government, or from any of Australia’s corporate lobby groups.

A left-of-centre think tank? Some idealist students writing an assignment on corporate ethics?

In fact they come from the Davos Manifesto 2020, drafted by Klaus Schwab, founder and Executive Director of the World Economic Forum. The WEF has been the global focal point for capitalism’s champions – ministers, presidents and prime ministers, CEOs of the world’s biggest companies – who every January for the last 50 years have been gathering in Davos, Switzerland, for what may be described as an upmarket Club Med celebration of capitalism.

Schwab writes about why we need an updated manifesto, a manifesto that goes along with a business philosophy known as “stakeholder capitalism”, which, as the above quotes suggest, is about a corporation’s broad responsibilities to all its stakeholders, and not just to its shareholders’ financial interests. For comparison he has a link to the 1973 Davos Manifesto, a document that is all about returns to shareholders and profit maximisation.

(Although Schwab correctly refers to “stakeholder capitalism” as a guiding principle in the 1970s, its values were first articulated during the Great Depression. In the 1930s academics such as Chester Barnard, Adolf Berle and Garnder Means saw that unless capitalism was to succumb to its own destructive forces, it had to be more inclusive. Stakeholder capitalism gave way to neoliberalism in the 1980s, but now that capitalism is once again losing its social license the idea of stakeholder capitalism has made a comeback.)

Climate change is not a matter of opinion

Both learned helplessness and short-termism yield a result that fits comfortably with those who still see climate-change as a matter of belief or ideology. Framing the most recent debates provoked by the bushfire emergencies as part of the “culture wars” reinforces the notion that climate science is a matter of belief, not scientific observation and extrapolation. No less importantly, because the debate remains framed as a debate about belief, learned helplessness and short-termism can be translated into the nativist-populist terms that now have such currency in many political systems.

This is an extract from remarks made by Kenneth Hayne at the Centre for Policy Development’s Business Roundtable on Climate and Sustainability last month. The CPD had drawn together representatives from Australian and global financial corporations, whose investment decisions are heavily influenced by firms’ approaches to dealing with climate change, as well as former and present senior Commonwealth public servants.

There was none of the thinking that we must choose between attending to our economic interests and dealing with climate change. The roundtable’s summary states “Australia’s economy and financial system is particularly exposed to climate impacts”: there is no tradeoff.

Investors with medium to long-term outlooks are increasingly demanding that firms have governance structures and plans to deal with the inevitable and probable impacts of climate change on their operations. To quote from CPD’s CEO Travers McLeod’s summary:

Those pushing for greater action on climate risk are a broad church. They are shifting the horizon not only because of compliance but because it is the smart thing to do. There is broad awareness that the climate crisis poses increasingly serious risks for Australian firms and investors, and that there will also be major opportunities in a zero-carbon transition. What is needed now is a concerted shift from awareness to action.

Corporate tax

The Australian Taxation Office has released its Corporate tax transparency report for 2017-18, covering large foreign-owned and Australian public companies. It shows tax collected by sector: the finance sector is the biggest contributor while mining has been the source of most of the growth in corporate tax collected.

If you follow a couple of links on the ATO site you can download an Excel workbook showing each company’s income, taxable income and tax collected. Of those 2246 companies, 582 had no taxable income, 145 had taxable income but paid no tax, 549 had taxable income and paid tax at less than the 30 per cent corporate rate, and 970 paid tax at the 30 per cent rate.

If you find downloading spreadsheets a bit of a drag, the ABC’s Nassim Khadem has some comment, analysis and explanation – ATO data reveals one third of large companies pay no tax – and a neat tool to search the data by corporate name.

China’s authoritarian model owes more to Stalin than to Hitler

Liberal MP Andrew Hastie, Chair of the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security, has written an article based on a speech he gave to the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung. His article Challenge to democracy to counter Russia, China outlines the way Russia and China, drawing on techniques used by Lenin, Stalin and Mao, and helped by modern technology, conduct hybrid and political warfare in pursuit of global strategic objectives.

He sees great power competition between authoritarian and democratic states as a contest of ideas, and he urges democracies to “enlist the full weight of democratic institutions” to counter this new version of warfare – war without bloodshed. He praises the media, including The ABC and the Age, for exposing foreign interference in Australia.

Unsurprisingly there has been criticism of his speech from the Chinese Government, resentful of Hastie’s comparison of China with authoritarian regimes of the past. Rory Metcalf of ANU’s National Security College defends Hastie against Chinese misrepresentations of his views: Hastie was pointing out the strength of China’s determination to disseminate its propaganda, using some methods of totalitarian regimes. Hastie was not drawing an analogy with Hitler’s murderous regime.

People from Hastie’s side of the political fence have been reluctant to speak out against the rise of authoritarian states. Parts of Hastie’s speech read like a welcome break from that silence. For example he writes “Authoritarian states have weaponised previously benign activities like diplomacy, media, investment flows, infrastructure development, and foreign asset purchases”. Unfortunately he weakens his message by confining his criticism to just two authoritarian states, when he could have named the governments of the USA, Poland, Hungary, Turkey, Brazil and Australia as other states whose national governments are drifting from democracy to authoritarianism.

Polls and surveys

There is a cornucopia of political polls and surveys this week.

Newspoll – a 52-48 lead for the Coalition

William Bowe’s Poll Bludger presents the Newspoll figures on voting intention. In spite of a week with quite a bit of bad news for Morrison, the Coalition’s primary vote is 42 per cent (41 per cent at the election), Labor’s is at 33 per cent (no change), the Greens’ is at 11 per cent (10 per cent at the election) and One Nation’s is at 5 percent (3 per cent at the election, but Palmer also got 3 per cent at the election so some of that 5 per cent may be ex-Palmer.) Statistically the safest conclusion is that on primary votes nothing has changed in the last seven months. On the question of “preferred prime minister” Morrison has a strong lead.

The poll also surveys voters on their ratings of Morrison and Albanese in relation to nine attributes. Mostly there is little difference in their ratings, but Morrison scores significantly higher than Albanese on “decisiveness and strength” and (astonishingly), on “having a vision for Australia”.

Essential report

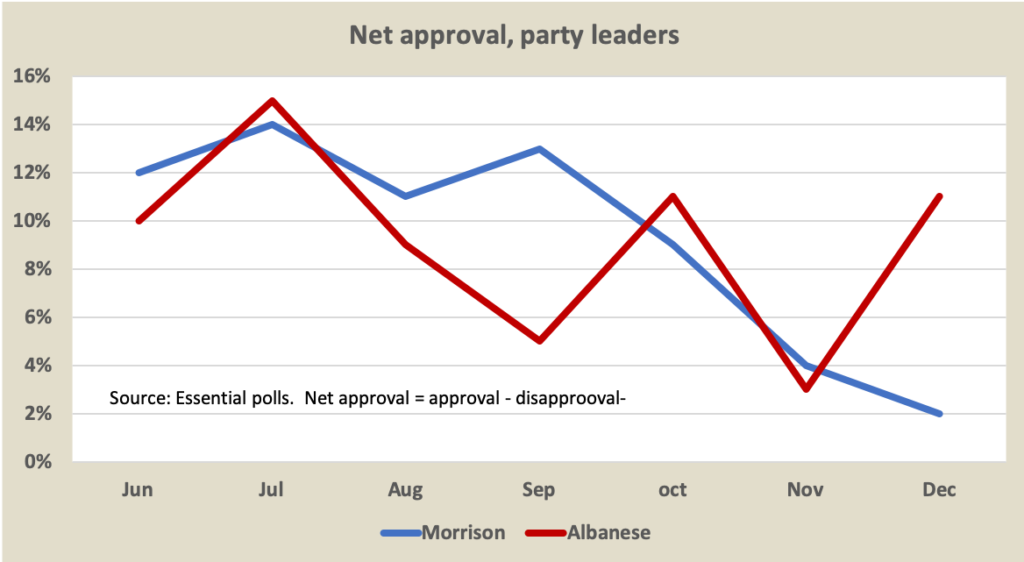

What is probably the last Essential Report for the year starts with leaders’ approval ratings. The chart below shows net approval (approval minus disapproval) for Morrison and Albanese.

The poll also asks whether Morrison and Albanese have met voters’ expectations, with fairly inconclusive results. (If you expected Morrison would behave like an overconfident and intolerant know-all, you might say he has exceeded your expectations).

It then has a set of questions on who or what groups we believe have found 2019 to be a good or a bad year. We think it’s been a good year for the Australian cricket team, large corporations, and for us and our families. It’s been a bad year for trade unions, small business, the economy and politics in general, and 2019 has been a particularly lousy year for the planet.

Most of us are easy with same-sex marriage, but 15 percent of respondents believe it has had a negative impact on Australia. (What have they seen or experienced that most of us haven’t seen or experienced?).

Our views on unions are mixed, and our views on Morrison’s treatment of Angus Taylor more or less follow party lines – that is among the half of the population who have been following the issue.

ANU’s Australian Election Study

The ANU Australian Election study (AES) was released on Monday. From the front page of its website you can download:

- The 1987-2019 trends report – 117 graphs, with data points, of people’s changing attitudes to political issues and perceptions of politicians;

- The 2019 election report – an analytical focus on the May election, with interpretation and some of the more salient findings from the 1987-2019 trends;

- The latest data – a set of data files in various formats (CSV, SAS etc), with enough to keep an analytical nerd occupied until writs are called for the next election.

A general impression from the trends document is that over the last 32 years Australians’ political attitudes have been shifting to the “left”, particularly on social issues, and that we are attracted to Labor’s policies on most issues, but what seems to push voters to the Coalition is a belief that it is more competent in managing the economy. In spite of accumulating evidence of the Coalition’s incompetence in economic management, belief in its competence is strengthening.

Another general impression, picked up by most media, is that trust in government is falling. A particularly telling graph shows that 75 per cent of Australians now believe “people in government look after themselves” (49 per cent in 1987). This suggests that Australians are coming to see “government” not as a body to attend to our shared interests, but as an entity with its own interests – in line with what is known as the “public choice” political model. (Have governments of the “right” deliberately cultivated this model to justify their “small government” agenda?)

Less publicity has been given to a set of findings confirming the general impression that the “rusted on” voter, loyal to a particular party, is a threatened species. Voters are becoming less loyal. One finding that may help explain the failure of polls to predict the election is that many Labor voters considered changing their votes during the campaign: it looks as if Labor has to work harder to retain its “base” than the Coalition does.

The election report is rich in detail. Contrary to the suggestion that the election was a Morrison-Shorten presidential-style campaign, only 7 per cent of voters nominated “party leaders” as the most important consideration. “Policy issues” scored 66 per cent as the most important consideration, and the leading issue was “management of the economy”. Also contrary to immediate post-mortems and claims promulgated by the finance sector, Labor’s policies to limit negative gearing and to limit franking credits had 57 per cent and 54 per cent support respectively. Global warming was an important issue to 81 per cent of voters, but there were strong (and predictable) differences by party affiliation.

Some early pundits suggested that women had deserted Labor in the election, but for most of this century so far Labor has done better among women than among men. Among women the Coalition primary vote was 38 per cent; among men it was 48 per cent. But not all that 10 per cent difference was to Labor’s advantage: 3 per cent was for Labor and the balance was for the Greens. (Why didn’t the suffragettes go one step further and disenfranchise men?)

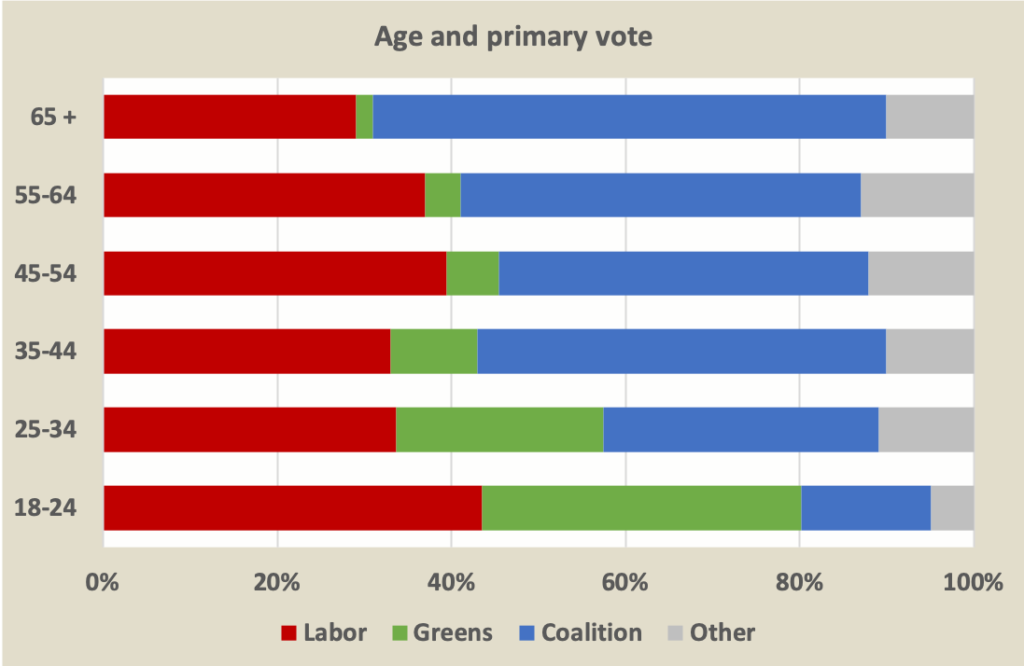

The most telling demographic divide was by age. The chart below is adopted from Figure 4.4 in the report. There is a clear negative relationship between voters’ age and support for the Coalition. (Other analysis suggests that this may be a cohort effect: as those who are young age, many will hang on to their preferences. If so, that means some Australians born in 2020 may live long enough to see a left-of-centre government again.)

Analysis of the AES data suggests that over time the intergenerational divide is hardening. This is confirmed by William Bowe, who has dug into the analytical data and has found that between the 2016 and 2019 elections, voters aged 18-34 have swung heavily away from the Coalition (a fall of 6 per cent), mainly towards Greens, while voters aged 35 to 54 have swung strongly to the Coalition (a swing of 8 per cent), while older voters haven’t shifted much. (It might be hard to find Bowe’s table – when last interrogated it was strangely filed with his Newspoll summary.)

The findings that will keep Labor analysts pondering for many years relate to social class, income, and education. In line with tradition, those identifying themselves as “middle class” went for the Coalition while the “working class” stayed loyal to Labor. But there was not a clear gradient in relation to income: the Coalition did better among those with incomes up to $40K than among those with incomes in the $40K to $80K band, and those with incomes above $130K, who predictably voted strongly for the Coalition, were also strong Green voters. On education, the Coalition did poorly among those with “no qualifications” and with “tertiary qualifications” (38 per cent in both categories), and well (46 per cent) among those with “non-tertiary qualification”, confirming impressions about “tradies” and their political support. (The AES does not classify a trade qualification as “tertiary”). The Greens did best among those with tertiary education.

People will inevitably have their own interpretation of the study, and as researchers pore over the data there will be more findings. Crikey’s Bernard Keane’s immediate summary (paywalled) was:

Australia’s political system is sick. Voters don’t trust it, they’re losing their faith in our democracy, they think it’s run for vested interests that wield too much influence.

Australia Institute on emissions target

A survey conducted by the Australia Institute has found majority (62 per cent of Australians) support for a national net zero emission target by 2050. There are partisan differences – Green voters 84 per cent, Labor 76 per cent, Coalition 62 per cent, One Nation 43 per cent.

The polling was in early November, before bushfires had reached their current level of ferocity.

Academia: from inefficient effectiveness to efficient ineffectiveness

That’s the title of a piece by Nicholas Gruen on Club Troppo. The university has been transformed from a body of scholars, committed to learning and adding to the world’s knowledge but doing it all in a rather cumbersome manner (effective but not efficient), to an entity driven by performance metrics, particularly publication counts (efficient but not effective). The old model needed reform – it was not necessarily the best way to select and reward talent and to serve the public interest served, but neither is the new model.

More on Morrison’s amalgamations: you don’t need advice when you know it all

Last week we covered John Hewson’s assessment of Morrison’s decision to amalgamate a number of Commonwealth departments. Hewson’s comments were mainly about Morrison’s devaluation of the environment, education and the arts, and his general disdain for policy processes. Laura Tingle takes up where Hewson left off: Inside the public service shakeup: what it really says about Morrison’s Government. The amalgamations aren’t really about improving administrative efficiency as Morrison claims: in fact they may make administration more cumbersome. Rather they are about doing away with troublesome senior public servants – the people who advise on policy. Morrison doesn’t need advice from anyone.

Health insurance

Health insurance emerges as a major election issue

Not here (as yet), but in the USA. As the time for Democrat primaries approaches (they kick off on 3 February), America’s health care providers and health insurers have become more concerned about candidates’ health financing policies, including “Medicare for all” as proposed by Warren and Sanders, and the model of a public insurer competing with private insurers as suggested by some ofher candidates.

Although (or because) a single national insurer would have public support, a lobby group calling itself Partnership for America’s Health Care Future (a front for health insurers, big pharma and the right wing of the AMA) has arisen to fight any suggestion of moving away from that country’s expensive and dysfunctional health care funding system. Mark Kreidler, writing in Capital & Main, describes its emergence and campaign tactics – Industry seeks to flatiine universal health care. (His article is re-posted in Fast Company, in a format that’s easier to read.)

Saving private health insurance

Steven Duckett and Matt Cowgill of the Grattan Institute have released their second report on saving private health insurance. In recognition of the failure of “community rating” (the set of arrangements whereby younger members of PHI subsidise older members), it recommends partially de-regulating PHI for members under 55, scrapping rebates for ancillaries (dental etc), abolishing the Medicare Levy Surcharge (which rewards wealthier people for not contributing to Medicare) and paying specific subsidies for PHI members over 55.

(The report ducks the question why there is any point in saving PHI, is a high-cost means of doing what Medicate and the Australian Tax office do far more efficiently and without violating the principle of universalism. Subsidies PHI are costing around $11 billion a year – not the $6 billion used in the report.)

Premium rises

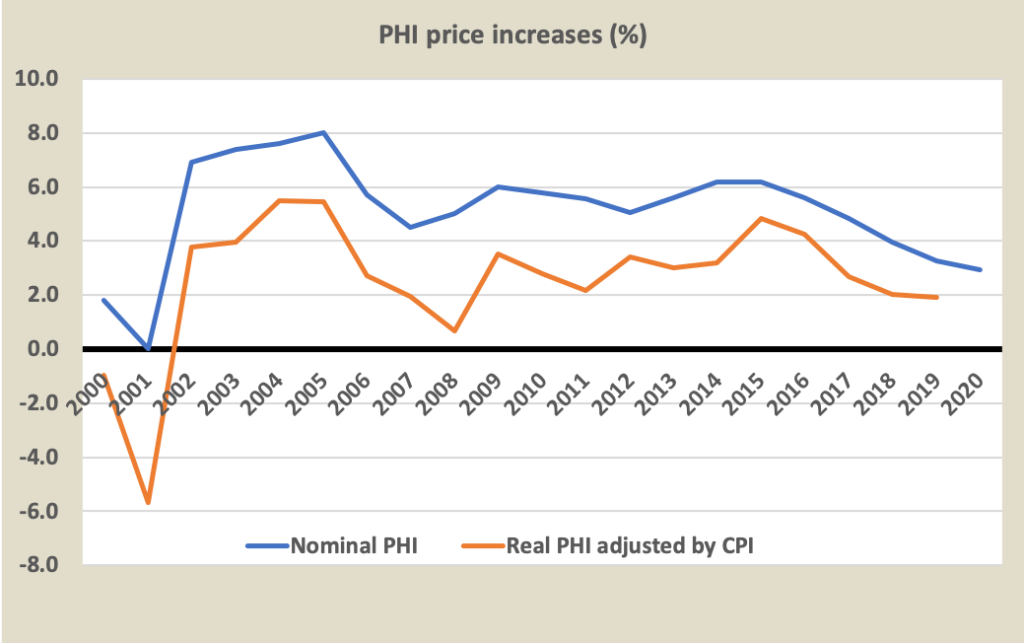

While on the subject of health insurance, below is a chart of premium rises allowed by successive Australian governments. Lowest in 19 years as the government claims? Only if you disregard inflation.

Arms sales are on the way up

The world economy may be hobbling along, just avoiding a recession, but the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) reports that arms sales by the sector’s hundred largest companies (excluding China for which they have no reliable data) increased by 4.6 per cent last year, to $US420 billion. Most of the growth last year was from US and French firms and the US still dominates, accounting for $264 billion of that $420 billion.

America is in a “treason” boom

There was a time when the words “traitor” and “treason” had meaning. They applied to the most serious cases of betraying one’s nation’s most vital secrets or interests. But Trump and his cronies, in accusing anyone who stands in his path of treason, has devalued the language. That devaluation makes it hard for the public to appreciate the gravity of the crimes committed by Trump and by those who, like defendants in the Nürnberg trials, claim they have simply been following his orders. So writes Rick Wilson in the Rolling Stone – The traitors among us.

The Australian Government wishes you a quiet Christmas and a docile new year

It’s not often that the Government asks us to post its messages, but we are pleased to oblige by providing a link to this end-of-year advice to Australians.

Saturday’s Good Reading and Listening is compiled by Ian McAuley

Watch out tomorrow, Sunday, for Peter Sainsbury’s Sunday environment round up.