What people in other forums are saying about public policy

America’s long road back to sanity

Biden’s inaugural address

You might care to invest 22 minutes listening to Biden’s inaugural address – maybe watching it because the Americans excel in the theatrics of state occasions.

Much of his speech comes across as a cut-and-paste of previous inaugurals, supplemented with quotes from Lincoln and the bible. That’s to be expected. There are plenty of phrases such as “all of us” and “we the people” – about as close as a Democrat dare hint at any notion of collectivism. Unsurprisingly he refers to the virus and to climate change.

There are also many words and phrases that go beyond the obligatory content, giving insight into Biden’s values, passions and priorities. He reminds us that “democracy is fragile”, he draws frequent attention to racism, and he makes specific references to “political extremism”, “white supremacy”, and “domestic terrorism”. He doesn’t mention Trump, but he does say “we must reject the culture in which facts themselves are manipulated and even manufactured”. Towards the end he sneaks in a reference to the problem of “growing inequity” as a problem – we wouldn’t expect to hear that in a Morrison speech. And in what must be a first for any such address, he manages to draw on St Augustine for political inspiration.

Biden’s formal address carries his explicit message. On another level you can hear his message to the American people and the world in Amanda Gorman’s poem The hill we climb. Americans may have built ugly cities, operate awful airlines and make bland coffee, but none can match them for oratory.

The rioters on January 6 behaved disgracefully, but not as badly as 139 well-dressed members of Congress

The assault on Congress on January 6 will leave a lasting impression. Thanks to the idiots who filmed and posted their own vandalism there is plenty of graphic content.

Zeynep Tufekci, a contributing writer to The Atlantic, points out that the riot was not the most dangerous thingthat happened on that day:

The most dangerous part of that day for the country as a whole, however, was not what happened when the insurrectionists fought their way into the Capitol in the afternoon, but what happened just a few hours later on the floor. After all that mayhem, the legislators were escorted back to the chamber under heavily armed escort, and a stunning 139 representatives—66 percent of the House GOP caucus—along with eight GOP senators, promptly voted to overturn the election, just as the mob and the president had demanded.

A hopeful sign for the future is that 17 newly-elected Republican members of the House of Representatives have sent a letter to Biden saying that they would work across the table.

Where to now for the US

Stan Grant has been moved to write several thoughtful articles on the storming of the White House, revealing his distress and a deep concern for the future of the United States. In his most recent contribution – Can Donald Trump’s impeachment revive America’s faded promise of democracy? – he draws on the ideas of historians W E B Du Bois and Greg Grandin (author of The end of the myth), both of whom were concerned with the enduring influence of slavery.

Grant acknowledges the part played by economic conditions in fomenting resentment – the terrible inequality that has developed in this re-run of the Gilded Age. But he wonders if there are more intractable maladies that have given rise to Trumpism.

Is Trumpism something out of the ordinary, or is it a manifestation of something deep-rooted in the American culture, he asks. Is that a culture rooted in “whiteness” as Du Bois suggested?

Rotten to the core?

The systems of checks and balances that protected Trump’s attempts to overturn the election also make it difficult for the US to reform its flawed electoral processes.

That’s one of the points Francis Fukuyama makes in his reflection on the election – Rotten to the core? – how America’s political decay accelerated during the Trump era – published in Foreign Affairs. He reflects on partisan alignments that are no longer along traditional left-right divisions, but rather on the basis of identities: in fact the Republican Party has become more like a cult than a political party.

He wonders whether, in response to the election defeat, former mainstream Republicans will take back the Republican Party, or if Trump will retain his grip on the party. “At one extreme, one could imagine Trump and his hardcore supporters morphing into a terrorist underground, using violence to strike back at what they regard as an illegitimate Biden administration”.

America and the world had a narrow escape from Trump

Writing in The Atlantic, Adam Serwer takes us through a list of Trump’s assaults on good government, some of which succeeded and some of which failed: An incompetent authoritarian is still a catastrophe. Had the Trump administration not been so administratively incompetent it probably could have rigged the electoral system to ensure his hold on office.

Serwer’s main point however is captured in the title of his piece. Even though Trump was incompetent, he was still able to inflict great damage on his country.

The rest of the world that isn’t the USA

The world after coronavirus

Yogi Berra warned “Never make predictions, particularly about the future”. So, rather than making his own predictions, Adil Najam of Boston University interviewed leading thinkers on 101 distinct topics – politics, economics, foreign relations, technology, literature, science, security – with the common question “How might Covid-19 impact on our future?”. He has recorded each response in a five-minute video.

His own summary of these views, published in The Conversation, is that there is “no going back to normal”: I spoke to 99 big thinkers about what our ‘world after coronavirus’ might look like – this is what I learned. From that article you can link to the videos.

Kishore Mahbubani and Graham Allison are among the many who talk about China-US rivalry. Francis Fukuyama puts forward optimistic and pessimistic scenarios – no suggestion of the “end of history”. He sees the resentment and strife in the USA not so much in terms of inequities in material conditions but in the way so many people feel they are not accorded respect. Dani Rodrik sees a retreat from the hyperglobalised economy – a trend that started before Trump.

We have dipped into only a few of these contributions: wisely, the respondents don’t seem to be too categorical. To combine the most pessimistic, right-wing populism will continue to displace democracy and China-US tension will escalate. To combine the most optimistic, the pandemic is forcing countries together to confront common problems and has reminded us that our needs cannot be met by “small government” – a liberal era will emerge from the crisis.

How should the Biden administration deal with Russia

With Trump gone, Putin has lost a soulmate. That will make it a little easier for the Biden Administration to stand up to Russia. But there has to be much more on the US Government’s policy agenda towards Russia: the US must contain Russia’s expansionist tendencies while dealing with it on areas of shared interest. So writes Michael McFaul, former US ambassador to Russia in Foreign Affairs: How to contain Putin’s Russia.

The US has underestimated Russia’s power and influence – not only its still formidable military power, but also its economic power and its capacity to mount cyber warfare, and has tended to disregard Putin’s capacity to draw by his side anti-liberal authoritarians from western nations – Le Pen, Orbán, Farage, and until now Trump. “Putin has deliberately tried to position himself as the leader of the illiberal, conservative world—a role he defines in opposition to U.S. liberal internationalism.”

The Biden administration must strengthen defences against cyber-warfare, and work with other countries to uncover the flow of Russian money. Abroad it must strengthen NATO and establish a constructive relationship with Ukraine (a relationship that Trump badly damaged) and with other states bordering Russia.

Much of the work begins at home: “Putin has declared liberalism obsolete; the Biden administration must prove him wrong—first and foremost by renewing American democracy at home.”

(Note that Foreign Affairs allows the occasional visitor a limited number of articles, and has provisions for more regular readers. An online subscription is not expensive.)

Alexei Navalny’s return to Russia – will it move the crowds?

Rather than staying in safety in Germany, Alexei Navalny returned to Russia, knowing he would almost certainly be immediately incarcerated on trumped-up charges. Could his unfair imprisonment galvanise his supporters; will international outrage lead Putin towards liberalisation?

Writing in The Conversation, Alexander Titov of Ireland’s Queens University fears his sacrifices and bravery will come to nought: Novichok didn’t stop Russian opposition leader – but a prison sentence might. Navalny does not have a large following – after all the crowds didn’t come out in numbers when Putin tried to kill him with Novichok, and Putin has proven impervious to foreign criticism.

The United Kingdom’s peripheral forces

Last week we linked an article by Fintan O’Toole about a nascent movement in Northern Ireland to separate from Britain and re-join the Republic – a movement energised by Brexit. This week O’Toole has another article in the Irish Times, about a more advanced movement for Scottish independence, also energised by Brexit – Nicola Sturgeon’s staunch ally in her push for independence – Boris Johnson.

O’Toole lists a constellation of reasons for a growing Scottish desire for independence. One factor that has pushed the movement along was the way Johnson based his campaign for Brexit on English nationalism, thus reinforcing Scottish nationalism – a nationalism already based in part on a “European” identity.

The Australian economy

There’s more to Keynesian economics than counter-cyclical spending

Mike Keating, writing in The Conversation, takes apart the notion that the Morrison Government, in response to our pandemic-induced recession, is following a Keynesian path of macroeconomic policy: Despite appearances, this government isn’t really Keynesian, as its budget update shows.

It is certainly engaged in counter-cyclical spending (remember when the Coalition used to prattle on about Labor’s deficits?). Keating reminds us, however, that effective Keynesian management also depends on boosting wages to stimulate demand. The Australian economy is suffering the related structural weaknesses of low wage growth and low productivity, but the Morrison Government’s economic policies are not directed to structural reform. “Over time the weakness in demand is likely to lead to lower investment, slowing the take-up of new technology and slowing growth in productivity” writes Keating.

Who’s holding the cash

It took a freedom of information request by the media for the Reserve Bank to release a short paper Impact of monetary policy on savers, depositors & self-funded retirees. Its sensitivity lies in what it says about risk. To quote (after editing for style):

- increasing asset prices can induce borrowers to take on too much credit if accompanied by looser lending standards and/or optimistic assessments of risk;

- if price rises induce large amounts of new property construction, this can create an overhang of excess supply, causing prices to fall further.

That’s conventional Eco 1, advice the Morrison Government ignores in its lax attitude to housing price inflation.

The paper also has some graphical presentation of income and wealth distribution. The chart on household assets and liabilities sensitive to interest rate changes is scary – particularly as they relate to people aged 35 to 54 who are carrying high debt. Another chart shows the distribution of dividend income by wealth quintile: Labor has to find some way to tax this fairly rather than the dopey idea of disallowing imputation credits that it took to the 2019 election. Labor has dumped that policy, but it still has no proposal to tax so-called “self-funded” retirees – people who can enjoy investment income of $100 000 a year ($200 000 for a couple) without paying a brass razoo of tax.

Annual performance indicators on government services

Every year the Productivity Commission collates performance data from all states and territories on the efficiency, equity and effectiveness of a range of government services, and produces sets of indicators in its 2021 Report on Government Services.

This year sections are being released sequentially. The first two released on Wednesday cover community services (including aged care and services for people with disabilities) and housing and homelessness. You might have read in your state’s press that its aged care facilities compared well or badly compared with other states and the national average for compliance with service standards, or that the unit cost for protective intervention for children perceived to be at risk ranged from $864 in the Northern Territory through to $6154 in Tasmania, to illustrate two of the many indicators that can be obtained from the Commission’s website.

Any comparisons based on these indicators alone are close to useless (so why does the media keep reporting them out of context?). They are simply indicators, not measures, and for many tables the Commission has a user warning: “Most recent data for this measure are not comparable but are complete, subject to caveats”. Like all performance indicators they serve the purpose of stimulating further investigation by experts involved in specific areas of service delivery. On each topic the Commission has a large amount of interpretative material that give context to the raw numbers.

Australian politics

Albo re-commits Labor to the US Alliance; so what’s the fuss about?

In Anthony Albanese’s speech – US-Australia relations under a Biden administration – the media have focussed on his statements about Scott Morrison’s political affinity with Donald Trump. He points out that Morrison went on a campaign rally stage with Trump, that on a week-long visit to the US he failed to meet with any senior Democrats, and that, unlike other world leaders, including many from centre-right parties, he refused to disavow Trump’s incitement of the mob to storm the Capitol. “Morrison went too far – partly out of his affinity with Donald Trump, partly because of the political constituency they share”.

All valid criticism. Good diplomacy and personal affections are, or should be, entirely different matters, and our interests are not served if our relationship with the US is seen to rest on our prime minister’s endorsement of Trump’s indefensible behaviour or on their shared contempt for democratic institutions. Our prime minister should refrain from such political intimacy, no matter how closely their right-wing Weltanschauungen align.

The speech is actually a re-assertion of Labor’s commitment to the US Alliance – an alliance “underpinned by shared values and an alignment of interests”. Albanese summarises the diplomatic substance of his speech:

Australia should focus its engagement with the Biden administration on building an Indo-Pacific where the sovereignty of all regional states is upheld, international rules are respected, and open trade drives prosperity for all.

Some may agree, some may disagree, with Albanese’s stance on the US Alliance, but whatever view one takes on our relationship with the US, he is surely right to draw attention to the Morrison Government’s inept handling of foreign relations.

Trumpism in Australia

Even before he disgraced himself by stirring up an attack on Congress, Australians never had much time for Trump. But writing on Open Forum – Trumpism down-under – Mark Kenny points out that Trumpism has made its way into Australian politics. He summarises the Trumpian approach:

Notions of honour and tradition, long relied upon to protect probity and avoid conflicts of interest, can be ignored. Those seeking transparency or who uncover maladministration can be depicted as political opponents or extremists, motivated by hatred and prejudice.

Seven years ago New South Wales Premier Barry O’Farrell resigned over a bottle of Grange Hermitage; last year Premier Gladys Berejiklian held on through a close association with a disgraced MP who had been arranging property deals for commissions. At the Commonwealth level there has been a succession of scandals, including the sports rorts and the over-priced purchase of land at Badgery’s Creek – scandals that in earlier times and in other countries would have seen ministers out of office.

Kenny also draws our attention to the failure by senior Morrison Ministers to call out the behaviour of MPs Craig Kelly and George Christensen, who, in Trumpist style, have been spreading stories about election fraud and about left-wing agitators provoking the invasion of Washington’s Capitol.

Morrison Government Netherlands Government resigns over Robodebt wrongly accusing social security recipients of fraud

There are many media accounts about the resignation of the Netherlands Government over accusing people of welfare fraud. Deutsche Welle goes into a little more detail than the Australian press: Dutch government resigns over child benefits scandal. There were 10 000 families involved, who will be paid on average €30,000. That’s around €300 million, or $A480 million, in a country of 17 million. Scaling that up to Australia’s population would equate to around $A700 million here.

The Coalition’s Robodebt scandal has cost almost twice that amount – $A1.2 billion – but not a single minister, let alone a whole government, has resigned. In the Netherlands not only did the Government resign but so too did the leader of the opposition Labour Party, who had been social affairs minister when the government introduced its AI-driven debt collection system.

Quarantine exemptions

Over the last few months we have been struggling to reconcile the numbers of Australians stranded overseas with the number of quarantine places available. Our back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that almost everyone should be home by now. Perhaps the reason these numbers don’t reconcile is that there are still many Australians making short overseas trips – businesspeople and public servants – and that they are taking up places on their return.

Also it is clear that many people with political connections, Labor or Coalition, are afforded the privilege of making their own quarantine arrangements. On the ABC website Nadia Daly throws some light on the situation: Australia’s hotel quarantine exemptions explained: Who can get them, what are the reasons, and who is making the decisions?

The strength of our public health system relies on its being fair and being seen to be fair. Secrecy, inconsistency, and instances of political privilege undermine trust, putting the entire community at risk.

The pandemic’s progress

Australia

We have now enjoyed a few days without any detected community transmission. Because the New South Wales Government (unlike the South Australian Government) failed to act promptly on the northern beaches outbreak when it was first detected on 17 December, that original outbreak spread to other clusters in Sydney and to a few cases over the border.

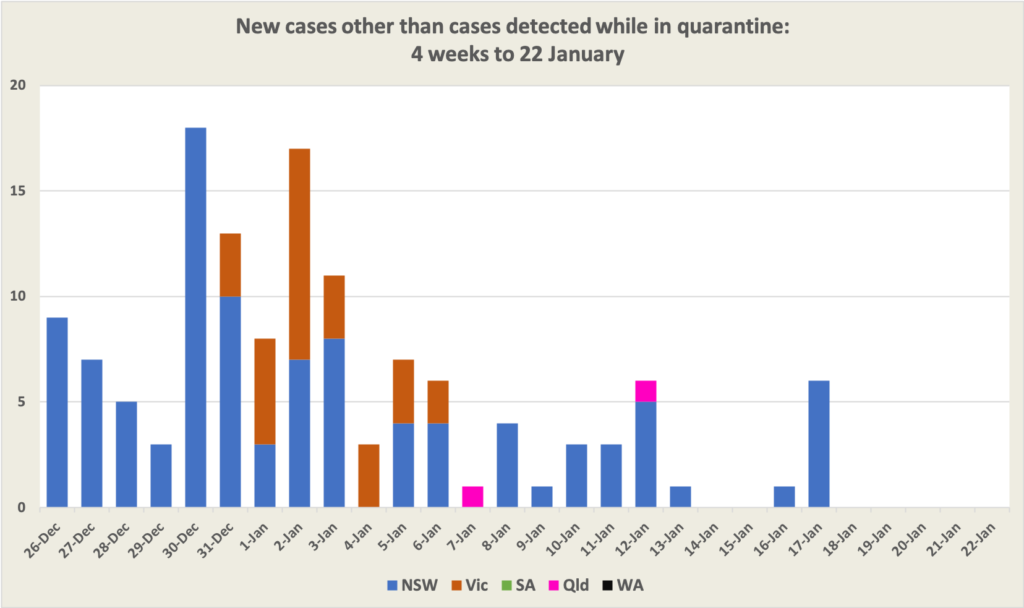

Cases for the four weeks up to Friday 22 January are shown below. All these cases, apart from one in Brisbane, are traceable to the New South Wales northern beaches outbreak.

On the ABC’s Coronacast Norman Swan interviews data journalist Catherine Hanrahan who has studied the behaviour of clusters in New South Wales. She finds that their contact-tracing process works effectively and it takes about three weeks to bring an end to a cluster (provided it hasn’t seeded any new clusters). On that basis, she estimates, the New South Wales outbreak should be ended by about now, three weeks after the clusters were discovered around New Year (see the graph), just before holidaymakers go back to work and school after Australia Day.

Even if there are no new cases from now on it won’t be until the end of the month that there has been a two-week period free of community transmission, and mid-February before there is a four-week period free of community transmission. These correspond to one and two cycles of the virus’s maximum reproduction periods, and are used for public decisions on border closures, and by people acting with caution in their private decisions on travelling and congregating.

The failure of the New South Wales Government to manage its quarantine system properly has imposed a high cost on the nation.

Our part of the world

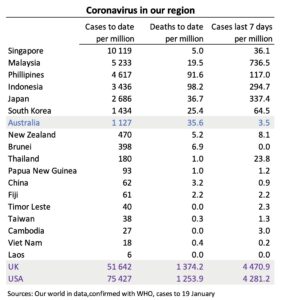

The table below is an update of the one we ran in November, covering countries in our region, and the US and UK – countries with which we often compare performance on other matters. For the most part we’re in a relatively safe part of the planet: even the worst-afflicted countries in our region are doing much better so far than the US and the UK.

Japan has recently had a growing number of cases, but its rate may have stabilised over the last few days. South Korea’s case rate is well on the way down after a recent spike.

Note that for some of the countries with less developed public health systems these figures probably understate the extent they have been affected with Covid-19. Also note that we have not included some small Pacific island countries.

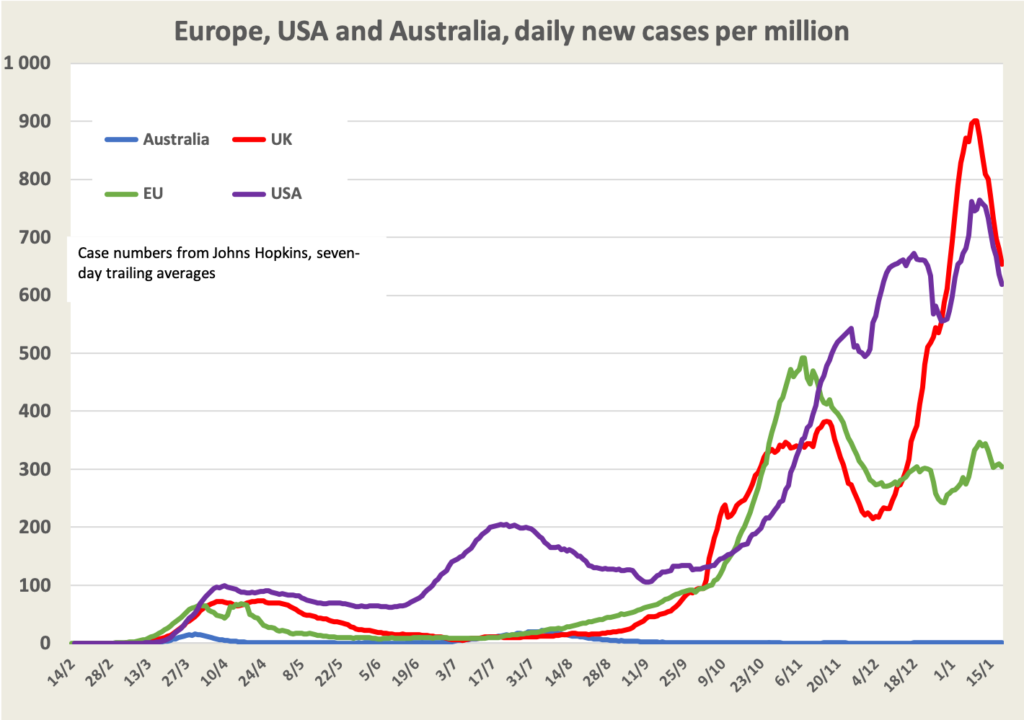

Countries further afield

The UK has been attracting a fair bit of media coverage recently for its high death rate. There are still countries, such as Italy and Belgium which, since the pandemic broke out, have had more deaths per million population, but their death rates have fallen in recent times, while they are still rising in the UK. The graph below, an update on last week’s, shows the UK’s case rate turning around, which points to a falling death rate in a few weeks. In the rest of Europe most countries are enjoying some reduction in case rates, presumably reflecting the effectiveness of restrictions on movement and association.

We will be watching countries that have active immunisation programs, but we believe it will be quite a long time before results become evident in the data, particularly if countries ease restrictions or if people become less cautious as immunisation rates rise.

The vaccine’s progress

The world is still not geared up to tackle Covid-19, and poor countries are being left out

Three articles, from different perspectives, draw our attention to global inequities in vaccination and misallocation of resources:

Producing a suite of vaccines in record time has been a marvellous achievement, but that’s about as far as the Independent Panel Progress Report to the WHO goes in congratulating those who are dealing with the pandemic (or who should be dealing with the pandemic). Shortcomings at each step of the global response to Covid-19 have worsened the situation. These include “a failure to measure preparedness in a way that predicted actual performance, and a failure of countries to prepare, despite years of warnings of the inevitability of a health threat with pandemic potential.”

There is a large amount of mitigation work to be done, not only in vaccine distribution, but in other public health measures, particularly as Covid-19 mutates into more infectious variants.

The Panel is most critical of the way rich countries are hoarding vaccines:

We cannot allow a principle to be established that it is acceptable for high-income countries to be able to vaccinate 100% of their populations while poorer countries must make do with only 20% coverage. COVID-19 did not start in the poorest countries, but they are suffering the greatest collateral damage, and they need enhanced solidarity and support from the international community.

A map on Page 6 of the report tells much of the story: at present rates, the vaccine won’t be available until 2022 or 2023 in most African countries, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, and in some countries in central America and Asia.

(The Panel, co-chaired by former New Zealand Prime Minister Helen Clark and Ellen Johnson, former President of Liberia, has a mandate to review experience gained and lessons learned from the WHO-coordinated response to Covid 19.)

WHO’s Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus is frustrated by the way the first to get the vaccines are in wealthy countries, ahead of health care workers and other vulnerable people in poor countries: WHO chief lambasts vaccine profits, demands elderly go first, published in Politico.

The article describes progress in the WHO’s COVAX program, which aims to distribute vaccines to all countries based on need. It has so far secured 2 billion doses (note that that’s enough to cover 1 billion people, in a world population of 8 billion – 6 billion people if China and other developed countries catering for themselves are excluded).

It also points out that the program does not include highly-effective mRNA vaccines – the “gold standard” for Covid protection.

“As of January 20, many more people have been immunised in Israel (with a population less than 10 million) than in Africa and Latin America combined”.

That’s a quote from Ilan Noy of the Victoria University of Wellington and Ami Neuberger of the Israel Institute of Technology – The big barriers to global vaccination: patent rights, national self-interest and the wealth gap – published in The Conversation.

World-wide total population vaccination is in every country’s interest, particularly in light of the virus’s increasing infectiousness, but governments, under pressure from their citizens, are prioritising their own citizens, particularly in materially rich countries, and big pharma “keeps a tight lid on the intellectual property it is developing in the new vaccines”. Global eradication or effective suppression of Covid-19 requires a global approach, similar to that applied to polio and AIDS.

Deaths in Norway

In the comments on last Saturday’s roundup there was a lively discussion on the deaths in Norway that had occurred after elderly people had received the Pfizer vaccine.

At this stage all we can say is that the death rate appears to have been around 1.5 in 1000 vaccinations, all or most of which were given to frail elderly people. We don’t know if there was any causal link between the vaccination and these deaths.

There is an account of these deaths by Ingrid Torjesen, writing in the British Medical Journal on 15 January. At that stage there had been 23 deaths of “very frail elderly patients with very serious disease” shortly after receiving the Pfizer vaccine. At that stage “more than 20 000 doses of the vaccine had been administered over the past few weeks”. Norway has prioritized immunizing nursing home residents, “most of whom are very elderly with underlying medical conditions and some of whom are terminally ill”.

Since then, according to press reports there have been more deaths – the total is “up to 30 ‘frail patients’”, according to ABC’s medical journalist Sophie Scott. We don’t know whether that higher number rests on the original 20 000 vaccinations or on a higher number including subsequent vaccinations.

Her article Why Norway’s reports of deaths in Pfizer vaccine recipients will help the TGA assess the drug suggests how our own Therapeutic Goods Administration is likely to use data from Norway and other nations.

On the same general issue the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report on incidences of people suffering anaphylaxis shortly after receiving the Pfizer vaccine (generally within 15 minutes). They have observed 21 cases in 1.9 million doses – 11 cases per million.

It is unfortunate that many journalists reported on the number of Norwegian deaths without also reporting on the numbers of vaccinations. This is irresponsible journalism.

Sources

Sources of generally reliable information and analysis about Covid-19 are on a separate web page. The Harvard Gazette reports that the emergence of more infectious strains from England and South Africa mean vaccination must be accelerated and that it is now unlikely that northern summer (June) will see a hoped-for return to normal.

Polls and surveys

Essential is back– not much has changed

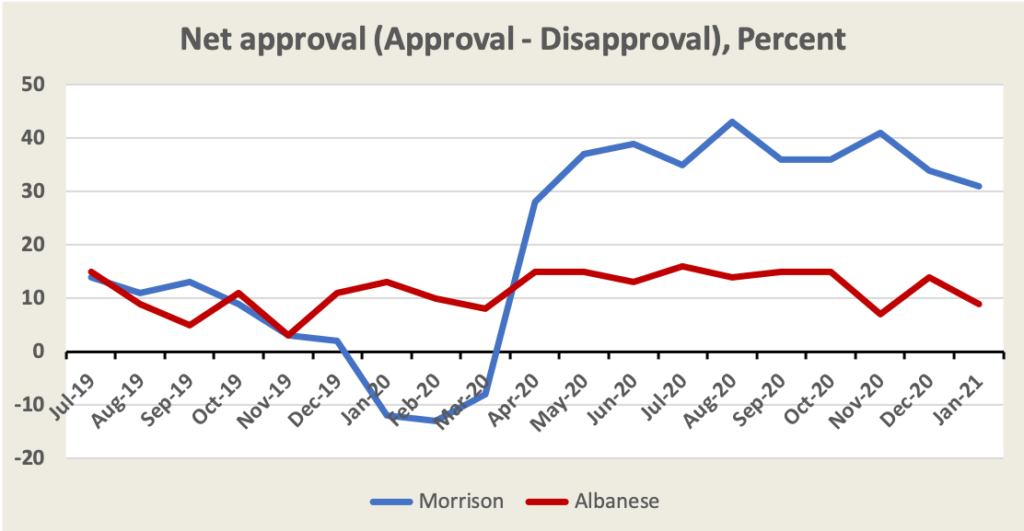

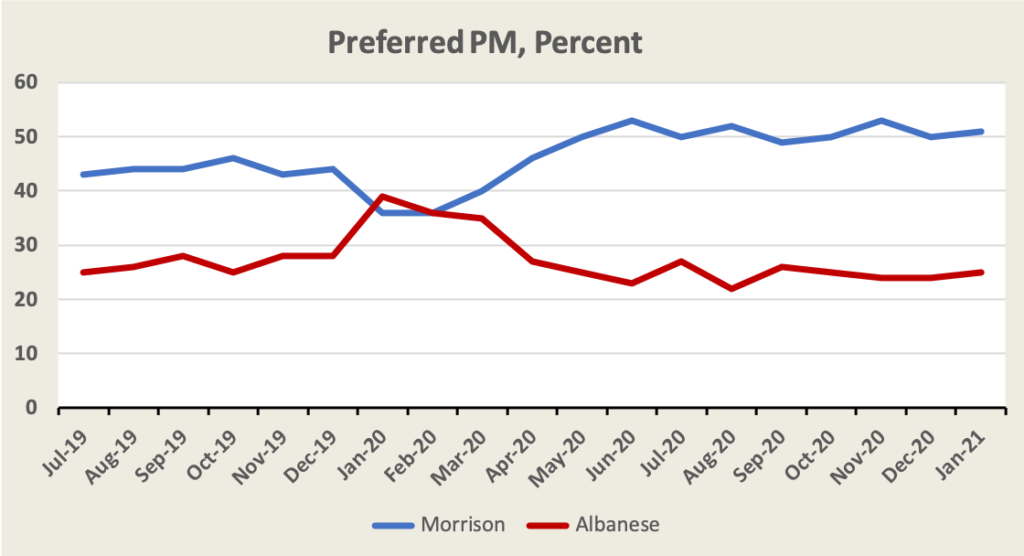

The Essential poll starts with views on Morrison and Albanese. As the graphs below show, nothing much has changed since the virus came into our lives.

We seem to be enthusiastic about vaccination against Covid-19: only 11 per cent of respondents say that they would never get vaccinated, but among those whose political affiliation is “other” (other than Labor, Green or Coalition) the “nevers” constitute 25 per cent. (This could cause some tensions in the Coalition when it comes to the prospect of doing preference deals with One Nation.)

There is a question whether we think “things got better or worse for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people over the last ten years”. Most people think they have stayed the same or improved: Coalition supporters are particularly likely to respond that conditions are getting better. It would be informative if, next time they ask this question, they could ask a representative sample of indigenous Australians.

There is a set of questions on Australia Day. To most, it’s “just a public holiday”. Just half of us would like a separate day to recognise indigenous Australians. Most people who would like a separate day want to keep January 26 as a holiday. There are predictable partisan and age differences in the responses.

Just on half of us think “It is likely that the bushfires are linked to climate change and it is appropriate to publicly raise this issue”. That view has solidified since January last year when the fires were raging. Unsurprisingly there are partisan differences: among Coalition supporters a quarter think “It is unlikely the bushfires are linked to climate change”; 43 per cent of Coalition supporters think “we are just witnessing a normal fluctuation in the earth’s climate; and 64 per cent think we are doing enough or too much to address climate change.

America’s 2021 Congress – Christians dominate

The Pew Research Center compares the composition of religious faith of members of Congress with the US population generally. While 65 per cent of Americans identify as Christian, 9 per cent as other religions, and 26 per cent as unaffiliated, in Congress 88 per cent identify as Christian and 12 per cent as other religions (6 per cent Jewish), while only one member identifies as unaffiliated – not enough to round up to one per cent. In relation to population Catholics, Anglicans (Episcopal) and Jews are significantly over-represented.

Only two members of Congress identify as “Pentecostal”.

Sport and unclassified ads

In praise of sporting diplomacy

Ramesh Thakur, a former Assistant Secretary-General of the UN and now of the Crawford School is a frequent contributor to Pearls and Irritations on foreign policy.

He writes on the Lowy Institute’s The interpreter about the latest developments in India-Australia relations:

Bliss it was to be a cricket aficionado in Australia at dusk yesterday as the shadows lengthened at the Gabba and the players were bathed in soft golden sunlight. To be an Indian fan was pure heaven. We are resigned to heartaches as a staple diet. But once in a while, the gods smile, all is good in heaven and the team delivers a sunbeam of a smile to every Indian cricket lover, all 1.3 billion of us. More prosaically, the series just concluded will do more to strengthen Australia–India bonds than any amount of public diplomacy by the two governments.

Situations vacant

The Centre for Policy Development, a body founded in 2007 by John Menadue and Miriam Lyons, has two vacancies – one for a policy adviser and the other for an economics adviser, both listed on the Ethical Jobs website and on the CPD website. The CPD is a truly independent progressive think tank, which has made substantial progress in shaping policies in a number of areas, particularly climate change. They’re an energetic and stimulating mob to work with, always open to new ideas and always committed to rigour in their policy-related work. You may be interested yourself, or you may know someone who is ready for a shift to more meaningful work.

Other aspects of the USA

A slideshow of 239 Whistler paintings (suggest you choose full screen)

Watch out tomorrow, Sunday, for Peter Sainsbury’s Sunday environment round up