Developing countries need help to avoid the clutches of the fossil fuel industry. Action is needed right now to combat climate change and the UK’s NHS is up for the challenge. 64 world leaders commit to ‘Living in Harmony with Nature’ to reverse biodiversity loss but Australia and Indonesia must have lost the invitation. China out in front on renewables.

Apart from the occasional page 7 item about conflict, kidnappings or famine, we don’t hear much about people’s lives or the environment around the Sahara Desert. I suspect that, like me, most P&I readers would be completely unaware that the four countries that occupy the Lake Chad Basin (can anyone even name them?) have applied to UNESCO for world heritage listing for the Basin on account of its natural and cultural significance. To the apparent surprise of Niger, Nigeria and Cameroon, Chad has now requested that UNESCO suspend the application while it redraws the borders of the proposed site. Reason: it is exploring oil and mining opportunities in the area. It would be easy for the rest of the world to sit back and take a ‘none of my business’ approach here but nothing is further from the truth. We all know that African nations are beset with multiple environmental, health and social problems and that they have a need, and a right, to develop economically and socially. It’s no surprise that nations such as Chad will seek to generate income as best they can and if that means digging up fossil fuels, so be it – that’s how the rich nations got rich. If wealthy nations are serious about combatting climate change and other environmental problems they must be prepared to pump big money into nations like Chad to help them develop alternatives to pumping oil. It won’t be enough for Australia to cut its own emissions and stop exporting emissions, it must also help developing countries establish economies that are not based on digging up or burning fossil fuels.

‘We can’t win this fight over the next 10 years but we can lose this fight over the next 10 years. It does not work to wait until 2045 and try to do it all then … because you will have already wrecked the planet’s climate system thoroughly. So all the work has to come right now.’ Bill McKibben, founder of 350, stressing the imperative for immediate climate action and targets focused on the short term, 2025 and 2030, not 2050 or even worse 2100. (Global Smart Energy Summit, 30 September 2020)

The role of a health service is to promote health and manage health problems for individuals and communities. It is, therefore, a bit disappointing to say the least when health services themselves create illness and premature death in the very process of fulfilling their assigned roles. But that’s the reality when it comes to climate change: health services are responsible for 5-10% of a country’s greenhouse gas emissions. And the harmful health consequences of climate change, already immense in Australia and globally, will inevitably get much worse. This week the UK’s NHS became the world’s first national health service to commit to becoming net zero. Specific commitments include: net zero by 2040 for the emissions that the NHS directly controls (with an interim target of an 80% reduction compared with 1990 by 2032); net zero for the emissions the NHS can influence but not directly control by 2045; purchasing only from suppliers who meet the NHS’s net zero requirements by 2030; and net zero emissions for the 40 planned new hospitals. This is not just about electric vehicles and LED light globes; this will involve changes to the way care is provided to patients that reduce the environmental impact while maintaining quality of care. In fact, by 2040 the NHS’s plan could save nearly 6,000 lives per year from reductions in air pollution and 38,000 lives per year from increases in physical activity. The Australian department of health has shown no interest in adopting similar goals despite the publication three years ago of a framework to assist them.

‘We are in a state of planetary emergency’, says the introduction to the Leaders’ Pledge for Nature issued by 64 countries (not including Australia) before the past week’s UN Biodiversity Summit. The Pledge recognises the need for transformative change to reverse biodiversity loss by 2030 and to ‘Living in Harmony with Nature’ by 2050. A couple of the pledges provide the basics:

- We will ensure that our response to the current health and economic crisis is green and just and contributes directly to recovering better and achieving sustainable societies; we commit to putting biodiversity, climate and the environment as a whole at the heart both of our COVID-19 recovery strategies and investments and of our pursuit of national and international development and cooperation.

- We commit to transition to sustainable patterns of production and consumption and sustainable food systems that meet people’s needs while remaining within planetary boundaries.

Specific actions focus on mainstreaming biodiversity into all policies; effective participation of indigenous peoples and local communities in decision making; scaling up nature based solutions to environmental problems; reducing harmful environmental and land-use practices; reducing pollution, including with plastics, of land, air, freshwater and oceans; aligning domestic policies with the Paris Agreement and achieving net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by mid-century; reducing illegal trafficking of wildlife and timber; reducing the impact of invasive species; and strengthening financial and non-financial policies to achieve human wellbeing and safeguard the planet. The signatories remain firmly committed to ‘sustainable growth, decoupled from resource use’. Justin Trudeau provided a brief but strong endorsement of the Pledge and committed Canada to protecting 25% of Canada’s land and oceans by 2025 and at least 30% by 2030. Did I mention that Australia hasn’t signed the pledge?

Indonesia hasn’t signed the Pledge either. This is a shame because after two years of little increase in deforestation, thanks to a $1 billion deal with Norway, forest loss has roughly doubled during COVID. Travel restrictions have limited the ability of law enforcement officers and civil society groups to monitor and stop illegal logging. Indonesian palm oil plantations expanded from 3.6 million hectares in 2008 to 18.8 million in 2019 and Indonesia is the world’s biggest palm oil producer, although clearing forests and peatlands for plantations or logging is now illegal in Indonesia. Forest and peat fires remain a problem. On top of all that, the Indonesian government is proposing to remove environmental protections to stimulate the post-COVID economy. On the way out are obligations to conduct environmental and social impact assessments for new licences, requirements for all regions to keep at least 30% of their territory as forests, and rules compelling companies to protect their land from fires.

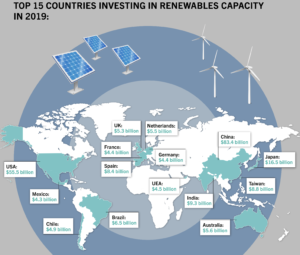

In the 2019 Renewables Investment Stakes, run on a sunny windy day, China galloped away from the field. The USA ran strongly but finished a distant second. The rest of the field trailed badly and was eventually brought home by Japan. (These are total dollars of course, unrelated to GDP or population size.)