The humble necktie (or ‘colonial noose’) remains a powerful symbol

Feb 25, 2021It turned into a prickly day in the Beehive in Wellington when Rawiri Waititi walked into Parliament wearing a large greenstone taonga around his neck, rather than a necktie.

House Speaker, Trevor Mallard, prevented Waititi from asking any questions, citing that members could only ask a question if they were wearing a tie. A formidable figure with his face almost totally tattooed, Waititi said Māori people had been facing such cultural discrimination for hundreds of years.

The incident kicked off a debate about colonialism (Waititi called the necktie ‘a colonial noose’) in New Zealand, and it spread by social media around the world. It led to Mallard’s advisory committee scrapping the requirement that men wear a tie in Parliament.

The tie

Accepted as a symbol of authority, wealth and (generally white) connections. It is, in fact, the only item that makes a dull suit interesting (although there is the kerchief or the buttonhole – i.e., flower). It remains stoically part of a business, political or social uniform that is worn almost worldwide. Some regard it is a status symbol; some as a silken shackle.

It is hard to reason why a tie (and accompanying suit) would make you a better lawyer, banker, a real estate johnnie, but not a better politician. The new blue-jeans billionaires from Silicon Valley have ditched the tie. As have entrepreneurs in the street wear and other non-conventional businesses. The popularity of ‘casual Friday’ shows that people are growing tired of the tie.

Ties of history.

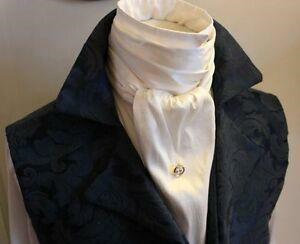

A tie is a long piece of fabric worn around the neck under the shirt collar and knotted at the throat. The modern long tie, the ascot and the bow tie are descended from the cravat.

A tie is a long piece of fabric worn around the neck under the shirt collar and knotted at the throat. The modern long tie, the ascot and the bow tie are descended from the cravat.

This was first worn by Croatian mercenaries serving in France during the Thirty Years’ War of 1618–1648. Their knotted neckerchiefs quickly came to the notice of fashionable Parisians. In Croatian they were hrvati but the French just adopted their nationality: Croates, which became cravate.

As a boy of just seven, Louis XIV began wearing a lace cravat in 1646 and the whole court toadily followed suit. The fad quickly spread all over Europe and men and women began wearing a piece of fabric around their necks. These became known as jabots.

In 1715, ‘stocks’ appeared. Originally made of leather and designed to make soldiers hold their heads high in grand military style, they also provided protection against stray flays from bayonet or sabre.

Stock ties were the civilian answer: usually just a piece of gauzy muslin folded into a long rectangle and wound several times around the shirt collar. The tie was fastened at the back with a pin, which was usually unseen because of long hair and wigs.

In the late 18th century, cravats began to make an appearance again and history tells us this was thanks to young Englishmen called macaronis, who brought the fashion back from their obligatory grand tours of Italy.

In the late 18th century, cravats began to make an appearance again and history tells us this was thanks to young Englishmen called macaronis, who brought the fashion back from their obligatory grand tours of Italy.

Debate arose about the correct way to tie a cravat, leading to the publication of a style manual called Neckclothitania in 1818. It listed 14 ways of tying a cravat, all as a way to enhance a man’s status and image as a style-setter. This was also the first book to use the word ‘tie’ to mean neckwear.

The Industrial Revolution meant people were busier and so wanted neckwear that was easy to put on. This led to the invention of the necktie we know today: long, thin, easy to knot (once you get the gist of it) and lasting the whole working day without coming undone.

Along the way, the bow tie appeared, a more convenient take on the cravat but the dickens to tie until you had a lot of practice. Black versions became de rigueur with dinner tails and white versions with appearances at court, possibly even just for the opera.

In 1926 the New York tie maker Jesse Langsdorf came up with a method of cutting fabric on the bias and sewing it in three segments, improving the garment’s ability to snap back into shape. This technique has lasted to this day.

In Britain and its Commonwealth countries, special striped ties suddenly appeared on the scene, their colours representing a school, regiment, club or some other organization. The stripes ran from upper left to lower right. The establishment menswear firm of Brooks Brothers introduced this tie to America but their stripes ran from upper right to lower left to set them apart.

Bold, colourful ties appeared after World War II when servicemen were anxious to get away from drab uniformity. The ties became wider and led to all kinds of loud decoration, some of it quite risqué.

The ‘Mister T’ look took over in 1951, an invention of the men’s style bible Esquire magazine, and dictated a new fashion that included a tapered suit, thinner lapel and a three-inch (7.6 cm) tie. Mr. T was, incidentally, only depicted as an illustration but he epitomised the ideal look for business, sport and ritual. He was streamlined and actually rather elegant.

Then came the small fashion revolution in the 1960s when men (especially Americans) decided they should ditch the tie and make their daytime attire the ‘safari suit’. I suspect no hunter ever wore anything approaching this and it was rarely in khaki – generally in ghastly pastel colors and made of polyester. But it took on the ’burbs with a vengeance to thankfully die a natural death a few years later (except in Surfers Paradise, where it may still be found on elderly gentlemen at the yacht club, with white shoes, of course).

After that ties became a fad, more often than not colourful. Couture houses made a thing of them – and charged accordingly. Even today, Gucci, Hermès, Charvet, YSL, Chanel, Dior and other fashion houses produce signature models but mostly in a uniform size.

Today, the tie comes in just about every fabric – knitted wool, woven tweed (popular with clan tartans), cotton, sometimes even awful man-made fabric… but silk remains the yardstick.

Meanwhile, International Necktie Day is still celebrated on 18 October in many cities, Tokyo, Dublin, Sydney, Como (centre of the Italian silk industry) and in Zagreb, where it all began centuries ago in Croatia.

House Speaker Trevor Mallard may be in attendance, but you will be unlikely to come across Rawiri Waititi and his greenstone taonga. His stance may have been one of symbolics, but he proved that symbols matter, and how they can be powerful objects of change.