A bill to change the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conversation Act focuses on streamlining the approvals process and devolving federal powers to the states and territories. But the Act already fails to capture most impacts of development because it doesn’t consider them holistically.

Some 8 million hectares of potential habitat for listed threatened species and ecological communities was cleared in the states and territories between 2000 and 2017. More than 93% of this clearing was not referred to the Federal Government for an assessment under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Act, according to a study by Ward et al. in 2019.

And in an independent review of the legislation conducted by Professor Graeme Samuel, his Interim Report (2020) stated that: “The overall result is net environmental decline, rather than protection and conservation.” His final review released last week reinforced that position.

A bill is now before the Senate that will allow the federal government to devolve environmental assessment and approval powers to state and territory governments – a “streamlined” or “single-touch” approval process.

The Wentworth Group of Concerned Scientists has had a long involvement with the EPBC legislation, and we have a number of concerns about the bill.

While the federal government evidently sees as a top priority the need to streamline development, this is not the key rationale of the EPBC Act — namely: environmental protection on matters of national significance. The Act must therefore deliver better environmental outcomes as well as reducing regulatory burden and duplication for business.

As the EPBC Act is currently implemented, the Commonwealth is not required to consider cumulative impacts of development. Cumulative impacts are those that arise from many small impacts of development accumulating across a region resulting in irreparable environmental damage.

In assessing developments on a project-by-project basis, the EPBC Act therefore fails to capture most impacts and, as a consequence, it is death by a thousand cuts for threatened species and habitat.

A key driver for environmental change is global warming, especially with respect to habitat resilience. Fragmentation of habitats can create great difficulties in migration of species; heating and drying of our landscapes can induce increased fragility to many plant and animal communities.

The Wentworth Group is also concerned that the bill does not contain appropriate requirements for evidence-based and legally enforceable national environmental standards to ensure protection of matters of national environmental significance.

While a reduction in the apparent burden on business to navigate approval requirements is a worthy cause it should not be at the expense of tackling key issues that are causing “net environmental decline”, to which there is no end in sight. Project approval processes are not the root cause of these long-entrenched trends, despite what the national Cabinet seems to think so (SMH, 12-13 / 12/20).

The Wentworth Group argues that effective national standards are needed before devolution to the states and that cumulative impacts of development are accounted for in any decision.

We also need to be assured that states and territories will harmonize relevant legislation related to decision-making processes on matters of national environmental significance (MNES), and that there is an independent “cop on the beat”.

My experience at a state government level tells me that state agencies responsible for decision making on MNES will not only need sustained consistent guidance, but also financial support from the Commonwealth. The precedents do not augur well, given that states, for example, have to look after federal international obligations in managing Ramsar wetlands.

The Wentworth Group has also had a long involvement with the EPBC legislation. In 1998 Senator Robert Hill appointed me chair of the second State of the Environment report by (SOE, 2001), which highlighted difficulties the Commonwealth had in working with the states. The basic thrust of our report in 2001 followed that of the report in 1996 — that the environment of Australia was in decline, in particular biodiversity and matters associated with water.

Land clearing at a state level was proceeding at an extraordinarily rapid rate – with rates in the top three or four in the world.

The Group participated in the initial 10-year review (“Hawke Review”, 2009) and was invited to a Consultative Committee coordinated by the independent reviewer, Professor Graeme Samuel. Professor Martine Maron and I, two members of the Group, appeared before the Senate Inquiry into proposed changes to the Act on November 23.

We believe that national standards that account for the individual and cumulative impacts of development should be in the Act to achieve three key benefits:

- Australia’s environmental laws that are finally capable of tackling the main causes driving species extinctions

- Greater certainty and reduced complexity for businesses because all developers would be subject to a clear and consistent set of standards regardless of the location of the proposed development.

- Efforts of one state or territory to conserve matters of national significance will not be undermined by the lack of efforts of another.

Since its formation in 2002 members of the Wentworth Group have undertaken many studies aimed at arresting biodiversity decline in Australia. We have conducted a national environmental account survey that was brought to the federal government’s attention. We have offered advice on land-clearing issues to New South Wales. Work on the National Water Initiative and assessment of the Murray-Darling Basin Plan has occupied much of our time in recent years.

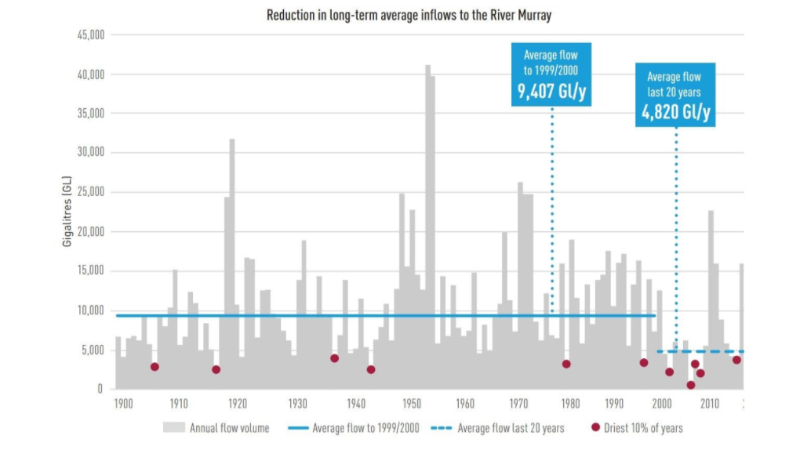

An example of new knowledge of change is the inflow water regime of the River Murray. This is shown in the accompanying diagram.

The 2020 Basin Plan Evaluation

Such changes in water flow have profound effects on environmental conditions. It highlights the need for flexibility in the Act to accommodate dynamic shifts in environmental conditions including areas of national/international significance such as Ramsar wetlands.

It is surely time to introduce into legislation a requirement that embraces adaptive pathways in MNES including cumulative impacts. That this can be done is shown, for example, in the NSW Coastal Management Act 2016, which allows for wetland migration linked to sea level rise.

State and territory governments are having to respond to the big challenges of forces of climate change. When it comes to matters of national environmental significance, they cannot be left to do it alone. It is now the time to recognise through reforms to the EPBC Act how best to manage MNES in a consistent, cooperative and national way.

Reforms to the EPBC Act are needed. But the Bill before the Senate fails to tackle ongoing causes of environmental decline which devolution and streamlining alone will not fix.