KATE GRIFFITHS,DANIELLE WOOD and TONY CHEN.Big money and the 2019 election (The Conversation 4.1.2020)

February 6, 2020

_Amid the ongoing bushfire and coronavirus crises – and the political kerfuffle surrounding the Nationals and Greens – you’d be forgiven for missing the annual release of the federal political donations data this week.

_

Nine months after the 2019 federal election, voters finally get a look at who funded the political parties’ campaigns.

The data reveals that big money matters in Australian elections more than ever, and donations are highly concentrated among a small number of powerful individuals, businesses and unions.

These are significant vulnerabilities in Australia’s democracy and reinforce why substantial reforms are needed to prevent wealthy interests from exercising too much influence in Australian politics.

Largest donations in Australian political history

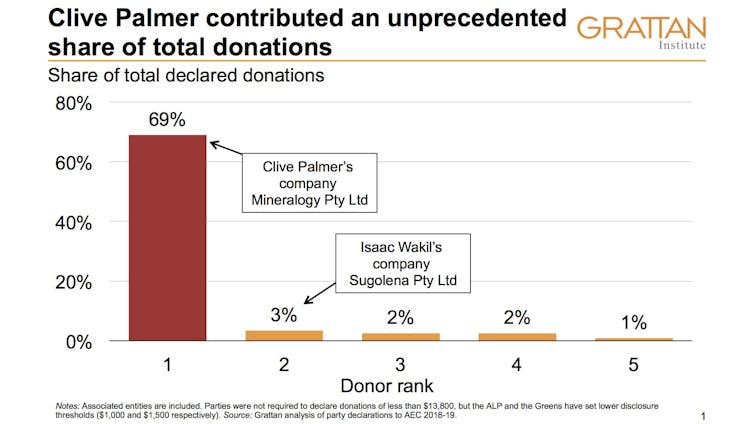

The big story of the 2019 election was Clive Palmer, who donated A$84 million via his mining company Mineralogy to his own campaign – a figure that dwarfs all other donations as far back as the records go. The previous record – also held by Palmer – was A$15 million at the 2013 election.

While Palmer failed to win any seats last year, he ran a substantial anti-Labor advertising campaign, and claimed credit for the Coalition’s victory.

There are obviously many factors in an election win, but this raises a serious question: how much influence should we allow any single interest to hold over the national debate, especially during the critically important election period?

Grattan Institute

Several other large donors also emerged at this election. A A$4 million donation to the Liberal Party from the company Sugolena, owned by a private investor and philanthropist, takes the prize for the largest-ever non-Palmer donation.

Businessman Anthony Pratt donated about A$1.5 million to each of the major parties through his paper and packaging company Pratt Holdings. The hotels lobby, which has been influential in preventing pokies reforms in past state and federal elections, also donated about A$500,000 to the Coalition and A$800,000 to Labor.

Money buys access and sometimes influence

A 2018 Grattan Institute report, Who’s in the room? Access and influence in Australian politics, showed how money can buy relationships and political connections. The political parties rely heavily on major donors, and as a result, major donors get significant access to ministers.

While explicit quid pro quo is probably rare, the risk is in more subtle influences – that donors get more access to policymakers and their views are given more weight. These risks are exacerbated by a lack of transparency in dealings between policymakers and special interests.

Big money improves the chances of influence. But it also matters to election outcomes.

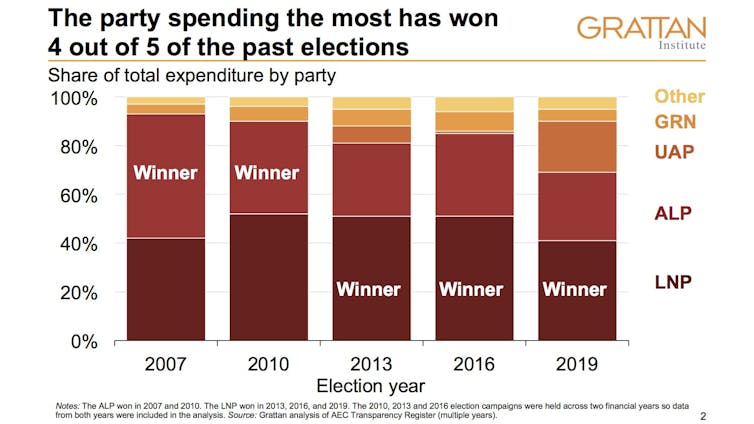

Looking back at the past five federal elections, an interesting correlation is evident: the party with the biggest war chest tends to form government.

It’s only a sample of five, and it’s unclear whether higher spending drives the election result or donors simply get behind the party most likely to win.

But in 2019, Labor was widely expected to win, so its smaller war chest supports the proposition that money assists in delivering power.

Grattan Institute

What policymakers should do to protect Australia’s democracy

Money in politics needs to be better regulated to reduce the risk of interest groups “buying” influence – and elections.

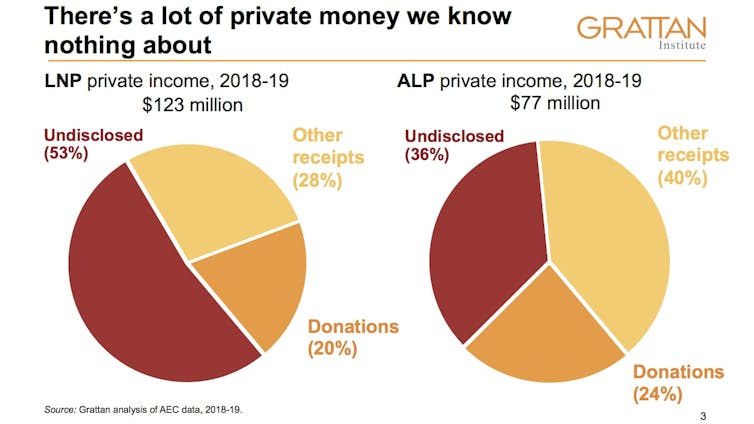

Real transparency is the first step. Half of private funding remains hidden from public view due to Australia’s high disclosure threshold and loopholes in the federal donations rules.

Only donations of more than A$14,000 need to be on the public record, and political parties don’t have to aggregate multiple donations below the threshold from the same donor - meaning major donors can simply split their donations to hide their identity.

Grattan Institute

Parliament should improve the transparency of political donations by

- lowering the federal donations disclosure threshold to A$5,000, so all donations big enough to matter are on the public record;

- requiring political parties to aggregate multiple donations from the same donor, so big donors can’t hide

- requiring quicker release of donations data, so voters have information on who funds elections during the campaign – not nine months later.

These simple rule changes would bring Australia’s federal political donations regime in line with most states and OECD nations. The current regime leaves voters in the dark.

But the donations data shows transparency is not enough to protect Australia’s democracy from the influence of a handful of wealthy individuals. Ultimately, to reduce the influence of money in politics, parliament should introduce an expenditure cap during election campaigns.

Parties and candidates can currently spend as much money as they can raise, so big money means greater capacity to sell your message to voters.

Capping political expenditure by political parties – and third parties – would reduce the influence of wealthy individuals. And it would reduce the donations “arms race” between the major parties, giving senior politicians more time to do their job instead of chasing dollars.

Kate Griffiths is a Fellow, Grattan Institute,Danielle Wood is a Program Director,Grattan Institute and Tony Chen is a Researcher, Grattan Institute.