Let’s learn from this pandemic to be better prepared for the really big one

May 30, 2020

On 26 May, Chief Medical Officer Brendan Murphy said if Australia’s mortality rate matched the UK’s, we’d have had 14,000 Covid-19 deaths. This is just tautological rubbish. It would be just as true and equally pointless to say if Australia’s mortality rate matched Vietnam’s, we’d have zero deaths.

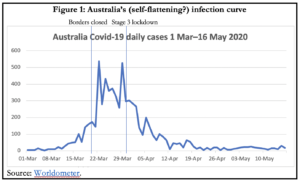

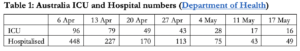

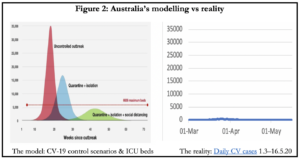

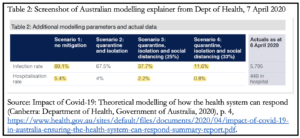

Table 2 is a screenshot of the table from Appendix A of the modelling published by the Government on 7 April. It may be the only objective check we have on assessing the accuracy of the modelling. Under the model’s best case Scenario 4, with tight quarantine, isolation and social distancing measures in force that reduce the rate of transmission by a third, 2.9mn people would be infected, 200,000 would require hospitalisation and nearly 5,000 people would need to be in intensive care (Figure 2) during peak demand. With infections just over 7,000 and ICU peak occupancy at 96, the predicted numbers are off by 400-fold and 50-fold respectively. If their best case scenario is this defective, there’s little reason to believe the other, including worst case, estimates of the modelling. Thus there’s no accurate measure of how many lives were saved by this level of intrusive state control.

‘So sometimes it’s more than just the science and the health, it’s about the messaging’.

Almost all journalists seem to have lost their cynicism towards claims by the authorities and instead become addicted to pandemic panic porn. The measures taken have been extreme, more even than has been done during a war and more than was attempted during earlier, deadlier flu epidemics. The authorities have told us who and how many are permitted into our homes, where we can and cannot go, how many people we can meet, where we can shop and for what, which services we can access and which not, even which medical and dental services we can still access. Who is going to call the Governments and the medical experts to account for the overreach?

A critical and sceptical profession would have put the government’s and modellers’ claims under the blowtorch and subjected them to withering criticism for the magnitude of errors by which their predictions have been off. Instead they have mostly joined the adoring multitudes in showering praise on the magnificence of the emperor’s new robe. Or, to change the metaphor, it is as if the Wicked Wizard of Wuhan (WWW) has cast an evil spell over the whole world and turned it into an enchanted forest with humans confined to limited spaces and the other creatures roaming freely, no longer terrorised by homo sapiens.

Looking to the future

Australia’s 50th biggest cause of annual deaths (110) is poisoning. At present, that is, Covid-19 does not make it to the top 50 causes of deaths. And for that we have inflicted such damage on people’s lives, livelihoods, education, freedoms, condemning them to house arrests en masse and robbing so many young of their future? If ever there was justification for a Royal Commission, this is it.

The point of the inquiry should not be to apportion blame for past mistakes. Rather, its primary term of reference should be to identify how we can prepare better for the next big one. In retrospect, we could have used the good fortune of the virus arriving in Australia in the latter part of summer, instead of in the middle of the flu season as in the northern hemisphere, to boost surge capacity at every bottleneck point to test, isolate, trace and treat cases.

One way or another, we will come out of this pandemic. But we can also be absolutely certain that it will not be the last pandemic to hit us. There will be others and next time we may not be fortunate in the timing (off flu season) or the geographical epicentre (North Atlantic). Also, the choice of Commissioners should reflect modern Australian demographics and the already evident reality that the best lessons to be learnt for successful responses are from Asia–Pacific countries. It’s both perplexing and irritating that, reflecting the composition of political and bureaucratic elites, Australia continues to look to Western countries to establish benchmarks.

Subject to change as the virus evolves, some things I would like to see begin with putting hard lockdown into the dustbin of history. And state border closures too, for that matter. Related to this, the government should provide the best available information and guidelines for individual and social health practices, but transfer the burden of risk back to individuals for assessing the dangers to themselves and the appropriate preventive measures to take and practices to adopt. A smarter approach is a more targeted approach, especially for an epidemic that is so strikingly age and gender stratified and in many jurisdictions has hit care facilities particularly badly.

We need surveillance mechanisms to identify and quarantine outbreak clusters backed by reliable contact-tracing methods. A team of scientists from Edinburgh and London has suggested a segmenting-and-shielding strategy that segments the elderly and frail while shielding their carers with adequate personal protective equipment. It is adapted from the ‘cocooning’ of infants by immunisation of close family members that is a pillar of infection prevention and control strategies.

The one thing in common that all the successful Asia-Pacific examples – Japan, Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, Vietnam, Singapore – have is they learnt from the earlier avian flu and SARS examples. They made preparations in advance and their institutions and procedures were activated with exemplary swiftness and efficiency. We certainly require prepositioned and pre-approved equipment and procedures for screening passenger traffic at air and sea ports on short notice, stocks of protective, preventive and therapeutic equipment and supplies, a surge capacity to break through the bottlenecks when we need to scale up, and the right balance between national manufacturing capacity and diversified global supply lines.

How can we best begin organising for the next health epidemic by way of institutions? The National Cabinet has been a good innovation. But we also need the equivalent of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ( CDC) and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control ( ECDC). Like the latter, I’d be in favour of a Trans-Tasman centre (TTCDC).