Environment: Australians must defend our right to protest

May 25, 2025

Dissent and protest are under attack across Australia. Thawing permafrost is a problem for everyone, not just Arctic-dwellers. LNG produces more emissions than coal, oil or gaseous natural gas. Renewables rollouts are up, but so are energy-related greenhouse gas emissions.

Defending dissent and protest

Governments across Australia are cracking down on dissent. Non-violent, though often disruptive, public demonstrations by environmental activists have been the focus of much of the governments’ ire but First Nations and human rights groups have also been targeted.

A report by the Australian Democracy Network and the Grata Fund makes the constitutional, common law and moral cases for protest, calling it “direct political participation that allows all of us to have a say in our shared future, and a method for the public to hold power to account, influence decision-makers and democratically counteract the undue influence of corporate lobbyists and connected power brokers”.

In Defence of Dissent identifies five broad themes in the repression of protest rights that have emerged in Commonwealth, state and territory legislation since 2019:

- Permitting the use of Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPPs) by corporations to intimidate or financially burden individuals and organisations advocating in the public interest.

- Criminalisation and more severe punishment of protest activities.

- Over-policing – for instance, with the use of pepper spray, tear gas and batons at protests, mistreatment of protesters in custody and intelligence gathering and surveillance to assist pre-emptive policing of protesters.

- Government misuse of emergency powers.

- Inappropriate use of protest notification and pre-approval regimes as de facto “authorisation” systems by governments.

The authors make many recommendations, including anti-SLAPP legislation, repeal of anti-protest laws, human rights acts, measures to prevent over-policing and inappropriate use of emergency powers, ensuring that relevant authorities follow correct legal procedures and respect for the Constitution’s implied freedom of political communication.

Who cares if permafrost is thawing? We all should

We all know that Arctic permafrost (permanently frozen ground) is thawing as the world heats up. This releases the CO2 and methane that has been locked in the frozen soils into the atmosphere, further contributing to global warming which causes more thawing in a vicious cycle.

Permafrost holds about 1.4 trillion tons of carbon – that’s nearly twice the amount that is in the atmosphere. So when people talk about coal mines and gas fields being “carbon bombs”, catastrophic though they are for climate change, they resemble festival firecrackers compared with permafrost Armageddon.

Unfortunately, the GHGs released from thawing permafrost are ignored in the climate accounting of the nations where it is occurring and in the global climate targets. This is because only anthropogenic GHGs are covered by the Paris Agreement and the thawing of permafrost is not considered to be caused by humans. While it’s true that humans have not directed millions of hot air blowers onto the permafrost to make it thaw, the thawing is an inevitable consequence of our burning of fossil fuels.

The outcome of these diplomatic shenanigans is that the magnitude of the global GHG problem is being underestimated and nations with large areas of permafrost such as Canada, US, Russia and the Scandinavian countries are either officially ignoring the issue or paying it mere lip service in their GHG reporting and climate action plans. More widely, the world’s collective Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) are already falling well short of keeping global warming under 2oC. If the GHGs released from permafrost were being factored in, the gap would be even greater.

The problems caused by thawing permafrost are not just national and global. There are serious local consequences as frozen ground softens and destabilises. Critical infrastructure such as homes, roads, buildings and pipelines is damaged. Indigenous communities’ lifestyles and cultures that are linked to the landscapes are destroyed. Animal and plant habitats and animal migration patterns are disrupted. Long-dormant, but potentially dangerous, pollutants and microorganisms can be released.

An abandoned US federal building sinks into the thawing permafrost in Alaska.

Unjustly, the humans who live on and around the permafrost, and who are suffering the local consequences of thawing, have probably made little contribution to global GHG emissions. The climate change consequences of thawing will, however, be felt by all nations, and, although Arctic nations and the UNFCCC are best placed to take the lead in tackling the permafrost problem, all nations need to be involved in solutions.

Antibiotics infecting our rivers and oceans

Each year, humans consume about 29,000 tonnes of the 40 most used antibiotics. Almost a third (8500 tonnes) are released into river systems and more than 10% (3000 tonnes) end up in oceans and inland sinks. Worldwide, about six million km of rivers contain antibiotic concentrations that are dangerous to the ecosystem, particularly during times of low water flow. Rivers in southeast Asia are the worst affected. Antibiotics in the environment also exacerbate the enormous problem of increasing antibiotic resistance.

As antibiotic use continues to grow, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, the problem is only going to get worse. The world needs new strategies to minimise antibiotic pollution of sewerage systems and rivers, safeguard water quality and protect human health and ecosystems.

The numbers above relate only to the human use of antibiotics. More than twice as much antibiotic is used during the production of animals that we eat and about a third as much in aquaculture, much of which occurs in inland seas. Antibiotics are even used on some fruit trees.

Producing and transporting LNG is highly emissions-intensive

The production of Liquefied Natural Gas is particularly energy-hungry. This is largely because turning natural gas, which is mainly methane, into a liquid of much smaller volume involves cooling it to -162oC. To produce LNG for export, the Australian gas industry uses the equivalent of a tenth of the energy contained within the exported gas. That’s about 10% more energy than is used by Australia’s domestic energy sector or our manufacturing sector.

Transporting the LNG overseas also produces a lot of GHGs. First, despite the liquid gas being very cold, some of the methane still evaporates from the cargo tanks – a form of fugitive emissions.

Second, many of the transport ships burn some of the LNG they are carrying to power their engines. The amount used has increased in recent years because more LNG is being shipped around the world and because climate change and political factors have increased shipping distances.

For instance, the US is now a major exporter of LNG, having increased its exports six-fold between 2017/18 and 2023/24. But closure of the Panama Canal, due to drought-induced low water levels, and avoidance of the Suez Canal for safety reasons have necessitated longer journeys around the Capes of Good Hope and Horn. Consequently, the GHGs produced from exporting the US’ LNG have increased from 4 to 18 million tons of CO2 equivalent over the last six years.

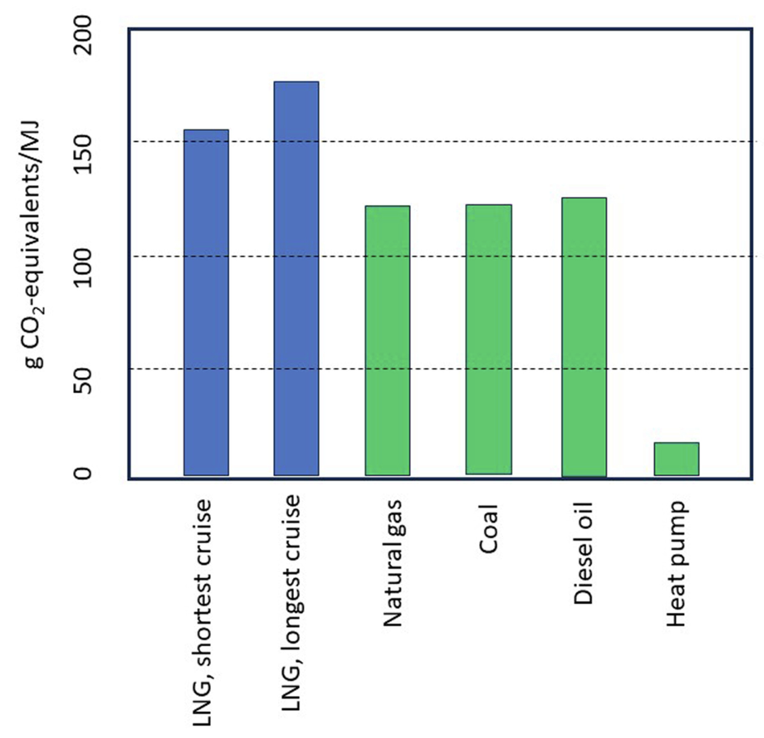

Still in the US, in round figures, of the GHGs produced during LNG’s full life cycle, 50% are created during production, processing and transport of the original (gaseous) natural gas, 35% when the gas is burnt by the final consumer, 10% during liquefaction, 5% during sea travel, and 3% between arriving at the destination port and reaching the consumer. The bottom line is that comparing emissions over each fuel’s full life cycle, for each unit of energy generated the US’ LNG produces about 33% more GHGs than the natural gas, coal or oil that are produced and burnt within the US. (Somewhat surprisingly, the emissions associated with each of the locally produced and burnt fuels are remarkably similar – figure below.)

So much for gas being the clean, climate-friendly, healthy, transition fuel of the future.

Aussie banks still funding fossil fuels

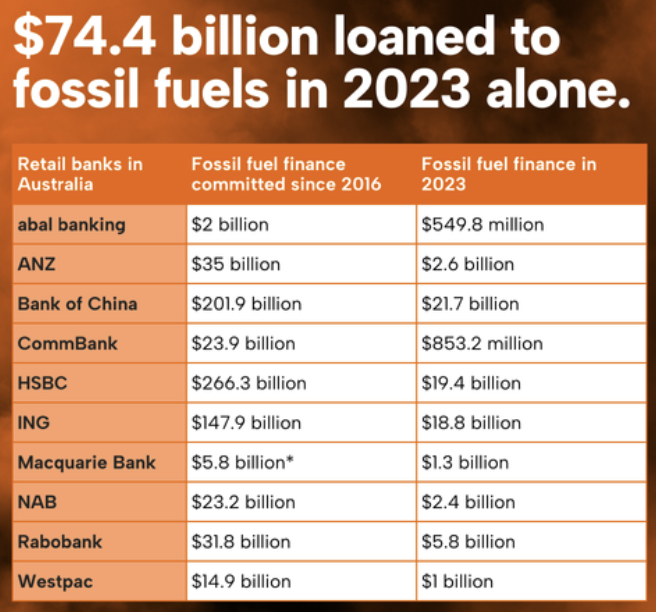

Australia has 103 retail banks, but only 18 provide finance to fossil fuel projects – more than $74 billion was provided by the top 10 lenders in 2023. Between 2016 and 2023, these 10 funded coal, oil and gas to the tune of $750 billion. The biggest financiers were foreign-owned banks operating retail services in Australia, principally Bank of China, HSBC and ING.

A worrying trend is for banks to adopt policies that end their funding of specific fossil fuel projects, but continue to allow them to fund fossil fuel companies’ general activities and issue bonds rather than loans.

Australia’s four main high street banks provided only about 10% of the funds provided by all Australia’s banks. However, this equates to almost six times as much money to the fossil fuel industry each year as it would cost (approximately $1.3 billion) for eight Pacific countries (including PNG and Fiji) to transition entirely to renewable energy. If Australia wants to get the Pacific nations on side for the COP in 2026, tacking this imbalance might be one project they’d like to put on the table.

Customers who have left one of the big banks because they lend to fossil fuel projects might not be aware that quite a few of the smaller banks are actually owned by the big four, e.g., Bank of Melbourne, BankSA, Bankwest, Citi, RAMS, St George, Suncorp Bank and UBank.

Renewables up, fossil fuel consumption up, power sector emissions up

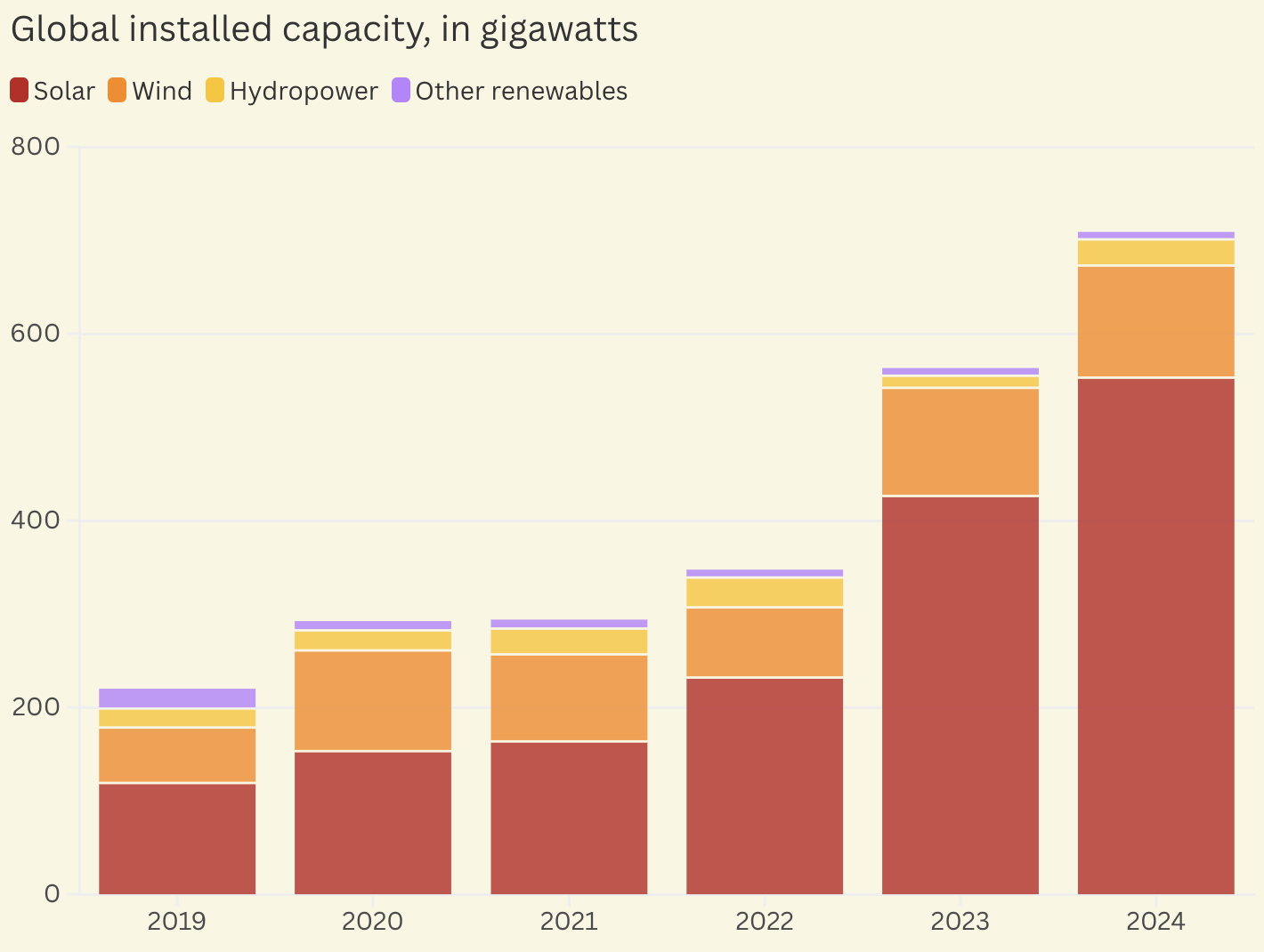

In 2024, the world installed more than 700 gigawatts of renewable energy. That was more than double the amount installed just two years earlier. Renewable (non-nuclear) sources produced 32% of the world’s electricity in 2024.

But, compared with 2023, power demand increased by 4.3% in 2024, power plants burned 1% more coal, gas and oil and global emissions from the power sector increased by 1.7%.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.