Aboriginal-Chinese roots of reconciliation: China’s first cultural envoys in Australia

June 22, 2025

As Australia marked Reconciliation Week (27 May – 3 June ), a landmark exhibition at the National Museum of Australia reminds us that Indigenous–Chinese bonds helped forge the links between the two peoples long before Canberra and Beijing formalised diplomacy in 1972.

_Our Story: Aboriginal–Chinese People in Australia_, a five-year research project led and curated by Chinese-Australian artist Zhou Xiaoping, uncovers a legacy of resilience and cultural fusion. Mixed-heritage communities — unwitting pioneers of people-to-people diplomacy — wove ties of survival and solidarity on 19th-century goldfields and in pearling camps. Drawing on historical records and oral histories, their stories — Our Story, the untold narratives of the nation — challenge monolithic accounts of Australian history and reveal a pre-modern form of “ soft power".

Through videos, installations, and embedded texts in family trees and photographs, the exhibition invites contemporary Aboriginal artists to interpret these “our stories". Together, they illuminate the accidental diplomacy of Chinese men and Aboriginal women who built communities against the odds.

One identity, two cultures

During the gold rushes and in industries such as pearling, railways, and agriculture (1850s–1900), Chinese labourers settled across northern Australia – from Darwin to Broome and Thursday Island. With few European women present, many young Chinese men formed unions with Aboriginal women despite the White Australia Policy and state protection acts.

These families blended Chinese traditions — language, cuisine, festivals — with Aboriginal kinship and cultural practices. Market gardens, modelled on China’s ancient farmers’ markets, supplied local communities, while Aboriginal art adopted Chinese motifs. “I’m Aboriginal, but I’m also proud of my Chinese heritage,” says Peter Yu, whose family photographs in the exhibition tell the story of how his Hakka father and Yawuru mother raised nine children under restrictive cohabitation laws.

Survival demanded ingenuity. In the 1930s, Wen Liqun registered her Larrakia stepson — her Chinese husband’s son with a Larrakia woman — as “Chinese” to shield him from the Stolen Generations. Family portraits reveal persistent “Chinese attributes” – features some descendants once masked with make-up to avoid discrimination. Photographs annotated with text and family trees strung across seed-packet bunting testify to the resilience of one identity under two cultures.

Materials as art

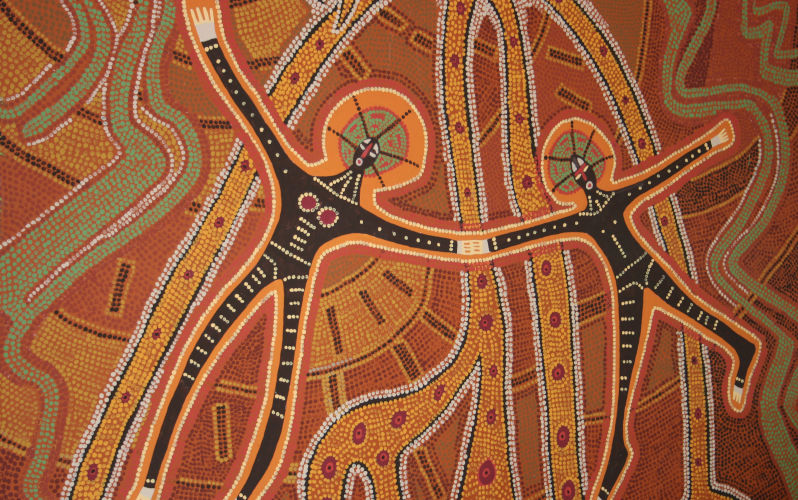

The exhibition’s artefacts reveal a pragmatic syncretism born of shared labour and creativity. Delicate glass sculptures of bok choy leaves recall market-garden exchanges, where Aboriginal land-care wisdom met Guangdong cultivation techniques. Pearl-shell artworks from Broome bear both Song-Dynasty motifs and Indigenous totems – a testament to the pearling boom that once tied remote Australia to global markets.

Jenna Lee, a descendant of mixed Asian heritage, weaves Chinese calligraphy paper into dilly bags that double as lanterns. “It’s about reclaiming the ordinary as extraordinary,” she explains at the opening of the exhibition. “Everyday objects become divine.”

“These pieces are quiet rebels,” Zhou observes. “They prove that culture is negotiated daily in kitchens, gardens and kinship networks.” As First Nations artist of Chinese descent Gordon Hookey notes of his “Dragon Serpent” painting at the opening of the exhibition, “Viewers are transported into that moment with those two ancestral spirits – a generous invitation indeed.”

Truth-Telling in an era of geopolitical tension

Fast-forward to today, and Canberra’s soft power looks very different. The dilly bags and pearl shells of 19th-century market gardens have given way to corridors exporting iron ore, lithium, and rare earths to China: Australian critical minerals now fuel Chinese infrastructure and the green-energy transition; Chinese battery-powered heavy mining machines and trucks used in extraction and transport, along with value-added technologies for mineral processing, create jobs and generate revenue for locals. Yet these economic ties co-exist with strategic anxieties over submarine-cable security, supply-chain chokepoints, national security concerns about the Port of Darwin, technology leakage, and foreign-interference risks. In an era when China’s rise — especially its challenge to American technological supremacy — has stirred deglobalisation and rising nationalism, such anxieties have only intensified.

Despite evolved mechanisms — trade agreements and tech-transfer pacts rather than dilly bags and pearl buttons — the underlying imperative remains: trust, built through sustained people-to-people connections. Nineteenth-century families negotiated survival and community cohesion on society’s margins; today’s executives negotiate multi-billion-dollar energy-transition deals under government scrutiny and media watch, balancing economic diversification with security hedges. In that sense, the market-garden plots of Broome and the boardrooms of Perth share a common DNA.

The exhibition’s four themes — Connection, Identity, Family and Prosperity — mirror modern diplomacy’s pillars. “This isn’t just about politics; it’s about people,” argues Professor Peter Yu. “Long before ambassadors, there were Aboriginal mothers teaching their children to cook bok choy and bush tomatoes.”

The question Australia must confront

What, then, can policymakers learn from these pioneer envoys? First, genuine engagement often thrives in informal spaces: academic exchanges, joint research projects and community festivals forge bonds more resilient than photo-op diplomacy. Second, reconciliation with First Nations people requires confronting the histories a nation once tried to erase. Publicly acknowledging mixed-heritage narratives signals to global Chinese diasporas and domestic audiences alike that Australia values its complex past. Third, soft power thrives on authenticity: the strength of Our Story lies in its unvarnished truths, not in state-sponsored gloss.

As the exhibition prepares to tour China in 2026, it forces a reckoning: how does a nation reconcile its suppressed histories with its multicultural present? By reconnecting with these hidden roots — embodied in everyday objects and intimate stories — Australia may yet forge its most resilient, relational partnership with China and its people.

“In an age of tariff wars and tech sanctions,” says Dr Jilda Andrews, curator of the museum, “Our Story isn’t just an exhibition. It’s a milestone in putting First Nations voices at the centre – creating a space for truth-telling, listening and honest conversation.”

The exhibition Our Story: Aboriginal–Chinese People in Australia runs at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra until 27 January 2026.

Republished from Australian Institute of International Affairs, 11 June 2025

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.