Ali Kazak and the transformation of the politics of Palestine in Australia

June 6, 2025

It was with great sadness that we learned of the passing on 17 May of Ali Kazak, at the age of 78. Over five decades, Ali dedicated his enormous energy to building understanding and support for Palestine, the land of his birth.

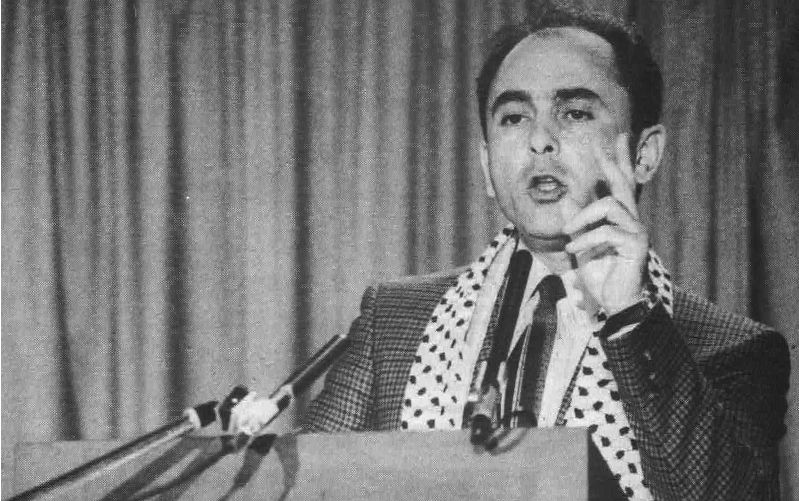

As a young activist, as the PLO representative and then Palestine ambassador, and as an educator and organiser Ali Kazak was, more than any other person, at the centre of the transformation of the politics of Palestine in Australia.

This was especially the case in the transition from the early-1970s — when Palestine was an unspeakable story in Australia — through to the 1990s, with successes including the recognition of Palestinian political rights, diplomatic status for Palestinian representation in Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific, and the enormous changes in public sentiment that made such progress possible.

Ali was born on 29 March 1947 to a Palestinian father and a Syrian mother in the city of Haifa in Palestine, then under the British Mandate. With the violent establishment of the state of Israel at the expense of the Palestinians and in their place, his mother fled to Syria seeking safety, amongst 900,000 Palestinians expelled from their homes as a result of terrorism and intimidation (the Nakba). His father stayed in Haifa. Ali explained:

“For 10 years my parents attempted many times to be reunited through the International Red Cross, but to no avail. In desperation, my mother crossed the border on foot at night, believing that once back in her own country she could not be legally deported, and that the authorities would allow me to rejoin them. However, two days later, my parents’ home was surrounded by Israeli troops, my mother was arrested and handed to the Red Cross for deportation.”

So he grew up in Damascus with his mother and his aunts, far from his homeland and his father, whom he would not see for 48 years. He studied at Damascus University and in 1968 joined the Palestinian National Liberation Movement, Fatah. Ali decided to travel, and in 1970 he arrived in Australia.

In the Australia of the early 1970s, the word “Palestine” was barely known, except as a place etched into war memorials commemorating Australian soldiers killed there in 1917-18 and in 1940-43. Zionism exercised ideological mastery: Israel was the “promised land” in the shadow of the Holocaust; it was “a land without a people for a people without a land”; Palestine was “a desert” and Israel “made the desert bloom”. Former Israel prime minister Golda Meir infamously claimed in 1967 that: “There was no such thing as Palestinians. They didn’t exist.” Israel with its “socialist” kibbutzim and Histradrut trade union federation was promoted as a left-labour ideal.

But it was not an empty land, any more than Australia was terra nullius in 1788. Former Israeli defence minister Moshe Dayan’s words in Yediot Aharonot on 10 May 1973 tell the story:

“It has to be said harshly: the state of Israel was established at the expense of the Arabs – and in their place. We did not come into a void. There was an Arab settlement here. We are settling Jews in places where there were Arabs. We are turning an Arab land into a Jewish land… They sit in their refugee camps in Gaza, and before their very eyes, we turn into our homestead the land and the villages in which they and their forefathers have lived… We are a generation of settlers, and without the steel helmet and the cannon we cannot plant a tree and build a house.”

This reality of Palestinian dispossession was understood by very few Australians 50 years ago. And Arabs were not in favour: by 1974, Australia and much of the world was in recession as a consequence of an oil crisis emanating from the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, when Arab OPEC members imposed an oil embargo against the United States in retaliation for the US resupplying the Israeli military and to gain leverage in the subsequent negotiations – a sharp contrast to the role played by those same states today in the face of Israel’s genocide in Gaza and continuing annexations in the West Bank.

At that time, Palestinian voices were rarely heard in Australia. Representatives of the PLO or affiliated organisations attempting to travel to Australia were often denied entry, a practice that continued until at least 1984, when the British writer Faris Glubb was denied entry for a planned speaking tour.

It was in this environment, of almost complete ignorance of the Palestine question, that Ali Kazak, as a young man, became an Australian citizen. Activist and solidarity groups existed in the big cities, comprising Arab and Palestinian Australians and supporters of the cause, but their voices were limited. Palestinian migrants were relatively new and few in numbers, the politics of the broader Arab-Australian community was heterogeneous, and Israel’s local political dominance meant there were few other supporters.

In 1974-5, leftist student activists pushed for campus affiliates of the Australian Union of Students to debate motions on Palestine as a means of raising awareness among a cohort of future political, community, trade union and business leaders. In fiery and sharply contested debates, the resolutions were in the main soundly defeated, but that was not the point. A flame of understanding about Palestine had been lit, especially with the 1975 appearance on the ABC TV’s premier current affairs program, Monday Conference, of Eddie Zananiri, an articulate representative of the General Union of Palestinian Students in Beirut. [Unfortunately, the tape of this historic event was “lost” by ABC archives.]

Kazak understood the significance of these events and built relationships across campuses and with activists. He saw that many of those engaged by the campus debates were moving into professional and politically-influential positions, and could form the basis of a more powerful advocacy network. His view was that the initial task — in that pre-digital era — was mass education, to overcome the pro-Irael hegemony by providing clear, evidence-based materials that spoke to the centre of Australian politics. In this, critical Jewish voices had an important role.

This education task became a mainstay of his activism over five decades. It found expression in the newspaper/magazine Free Palestine that he published – 56 issues between 1979 and 1990. Free Palestine became a core campaigning tool, a journal of record, an expression of a growing solidarity movement, a voice that was pitched to the many constituencies being built: students, labour activists, churches and community organisations. And within the political parties. Later there was Background Briefing (1987-93), two editions of the book The Jerusalem Question (1997 and 2018), a book on Australia and the Arabs (in Arabic, 2012), the backgrounding of media, and a constant flow of digital updates up to May 2025, daily at times of crisis.

Ali had a clear vision of a diverse network of constituencies that could be mobilised in a coherent advocacy effort. In 1982, the Palestine Human Rights Campaign was formed, linking groups around Australia and with New Zealand, with an advocacy focus on Palestinian rights already recognised in international law and by the United Nations, and the work of human rights organisations in Israel and internationally who were documenting and campaigning on issues ranging from torture in Israeli jails, to Israel’s foundation on race-based laws, and continuing Palestinian dispossession.

In the same year, Ali officially established the Palestine Information Office in Melbourne. A year earlier he had been appointed as the PLO representative to Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific region. These moves were the basis for a step-up in campaigning for the Australian Government to recognise both the PLO and Palestinian rights. During this period, speaking tours to Australia were organised for Ibrahim Abu-Lughod, characterised by Edward Said as “Palestine’s foremost academic and intellectual”, for the prominent human rights lawyer Jonathan Kuttab, Bishop Riah Hanna Abu El-Assal, the Palestine Red Crescent director Dr Fathi Arafat and PLO foreign affairs adviser Dr Nabil Shaath, amongst others.

By 1983, Yitzhak Shamir, formerly leader of the Zionist terror group Lehi, also known as the Stern Gang, had become prime minister of Israel, a post he held for seven years over two terms. Shamir’s politics became a model for Netanyahu, who was Israel’s UN ambassador at the time: terror has a great place to play in Zionism’s goals. In 1943 Shamir wrote:

“We are very far from having any moral qualms as far as our national war goes. We have before us the command of the Torah, whose morality surpasses that of any other body of laws in the world: ‘Ye shall blot them out to the last man.’ We are particularly far from having any qualms with regard to the enemy, whose moral degradation is universally admitted here. But first and foremost, terrorism is for us a part of the political battle being conducted under the present circumstances, and it has a great part to play.”

Eighty years later in Gaza, nothing has changed.

In Australia, Palestinians and Palestinian activists were under security agency surveillance, including phone taps and listening devices. ASIO perpetuated the myth of Palestinian “terror groups” in Australia, though, when pressed, was unable to provide a single example.

In May 1987, the PIO moved to Canberra, occupying a former diplomatic building close to Parliament House, and with a substantial flagpole from which Ali flew the Palestinian flag every day. This proximity to Parliament, from which the flag could be clearly seen, sent the Israel lobby into a frenzy of complaint, including letters to MPs demanding the office be closed “to ensure that Australia did not become a target for terrorism”. And not for the first or last time: by the time the second issue of Free Palestine was published in 1979, there had been threats to the printer and suggestions that they should not be dealing with “terrorists”. The printer declined this advice. That same year the Jewish Board of deputies tried unsuccessfully to have the licence of pro-Palestinian community radio station 3CR revoked.

In Canberra, the behaviour of the Israeli lobby did not endear them to the Department of Foreign Affairs, where Ali established good relations. At the same time, he established links and gained official recognition for Palestine from a number of Pacific states, the first being the Republic of Vanuatu in 1985. In early 1982, he met Foreign Minister Warren Cooper, which was the first official meeting with a PLO official by the NZ Government, triggering events leading to New Zealand’s recognition of the PLO in 1988.

In 1989, the PIO was officially recognised by the government as the Office of the Palestine Liberation Organisation, and in 1994 it became the General Palestinian Delegation. In 1990, Governor-General Bill Hayden officially met Ali Kazak as the PLO representative. As foreign minister, Hayden had met the PLO’s UN representative in 1985 in New York, and in 1980 as opposition leader had held talks with PLO chairman Yaser Arafat.

In May 2000, Prime Minister John Howard visited Palestine, including the Commonwealth Cemetery in Gaza where Australian soldiers are buried, and met president Arafat. During this time, until his term finished in 2006, Ali served as a representative of the PLO, the commissioner-general of the State of Palestine to Australia and New Zealand, and the ambassador of the State of Palestine to the Republic of Vanuatu, the State of Papua New Guinea, and the Republic of Timor-Leste.

Changes in Palestine policy in Australia were glacial, which tested Ali’s patience, especially at times of great destruction and in the face of Israel’s creeping annexations and ever-more-cruel practices. You could predict when Australia would make a policy move, Ali quipped; it would be a week after the Americans had.

On 18 February 1987, Ali Kazak became the first Palestinian invited to address the National Press Club in Canberra. He concluded his address:

“The international community supports the Palestinian claim to self-determination, but the moral and political challenges remain. How long can the attainment of Palestinian national rights be postponed? How many more Palestinians must be imprisoned, expelled from their land or massacred before Palestinian national rights are acknowledged, and consummated in an independent and sovereign state? Unless there is a positive response to these questions, the violence and the waste in the Middle East will continue.”

These political successes over two decades were built on a number of key understandings: the first, as already noted, was Ali’s commitment to education and outreach, and to engage and challenge the mainstream media, including an adjudication on 27 August 1986 by the Australian Press Council of untrue and stereotyped reporting of Palestinians by an Australian media outlet.

The second was the enormous effort to build a diverse and influential network of organisations and sectors and public officials in support of Palestinian rights. Ali and First Nations activist Gary Foley collaborated over many decades and projects, including more recently the Black–Palestinian Solidarity Conference at the University of Melbourne in 2019. He worked with many former DFAT officials and ambassadors, with church leaders, including Anglican Archbishop of Melbourne David Penman, with Muslim and Arab-Australian organisations, with union leaders and with many university educators.

Over many years, Ali’s networks and friendships were broad and sometimes surprising, covering all sides of politics. He had a warm relationship with National Party leader and Deputy Prime Minister Tim Fishcher, reflected in this tribute. And with former Liberal ministers, including Ian McPhee. After retiring as Prime Minister, Bob Hawke — who had substantially changed his views on the Middle East — welcomed Ali to his home in Sydney. Ali had helped set up parliamentary Friends of Palestine at federal and state levels, and enjoyed productive relationships with many current and former politicians, including Bob Carr, federal Speaker Leo Macleay and Senator Margaret Reynolds, to name but a few.

The third key to Ali’s work was a clear articulation of the task at hand. The framing of the issue was one of human rights and the right to self-determination, in language accessible and persuasive across the political spectrum. Goals and demands and messages were to be simple and clear, and pursued without distraction. It was a long game, demanding consistency and political discipline.

I am sure the many people who have known and worked with Ali felt his unique capacity and unrelenting determination, the fire in the belly, and his tireless work for Palestine and for truth, freedom, justice, and peace. That commitment was so deeply embedded that Ali rarely, if ever, took a day off.

On the other hand, I spent a considerable amount of time, along with the late Frans Timmerman, working with Ali on projects over two decades, and he was a gracious host, and a great cook of Palestinian food — a skill nurtured by his mother and aunts — and he appreciated a good Australian red. And he loved the music of Pink Floyd, among a broad taste in music.

As Pink Floyd’s David Gilmour and Roger Waters sadly wrote on an album of the same name, “Wish you were here”. Farewell Ali Kazak.

Note: The Ali Kazak Collection is at the Palestine Museum Digital Archive, and some of his archives are at the National Library.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.