Chalmers hints at more tax reform – What should we do first? Part 1

June 22, 2025

In the first of a two-part series Saul Eslake examines what the top tax reform priorities should be.

It’s refreshing to learn that Treasurer Jim Chalmers is willing to entertain more substantial tax reforms than the ones which Labor took to this year’s election (principally, the proposed increases in taxation of superannuation balances worth more than $3 million) in order to “ensure that the budget is put on a sustainable footing”.

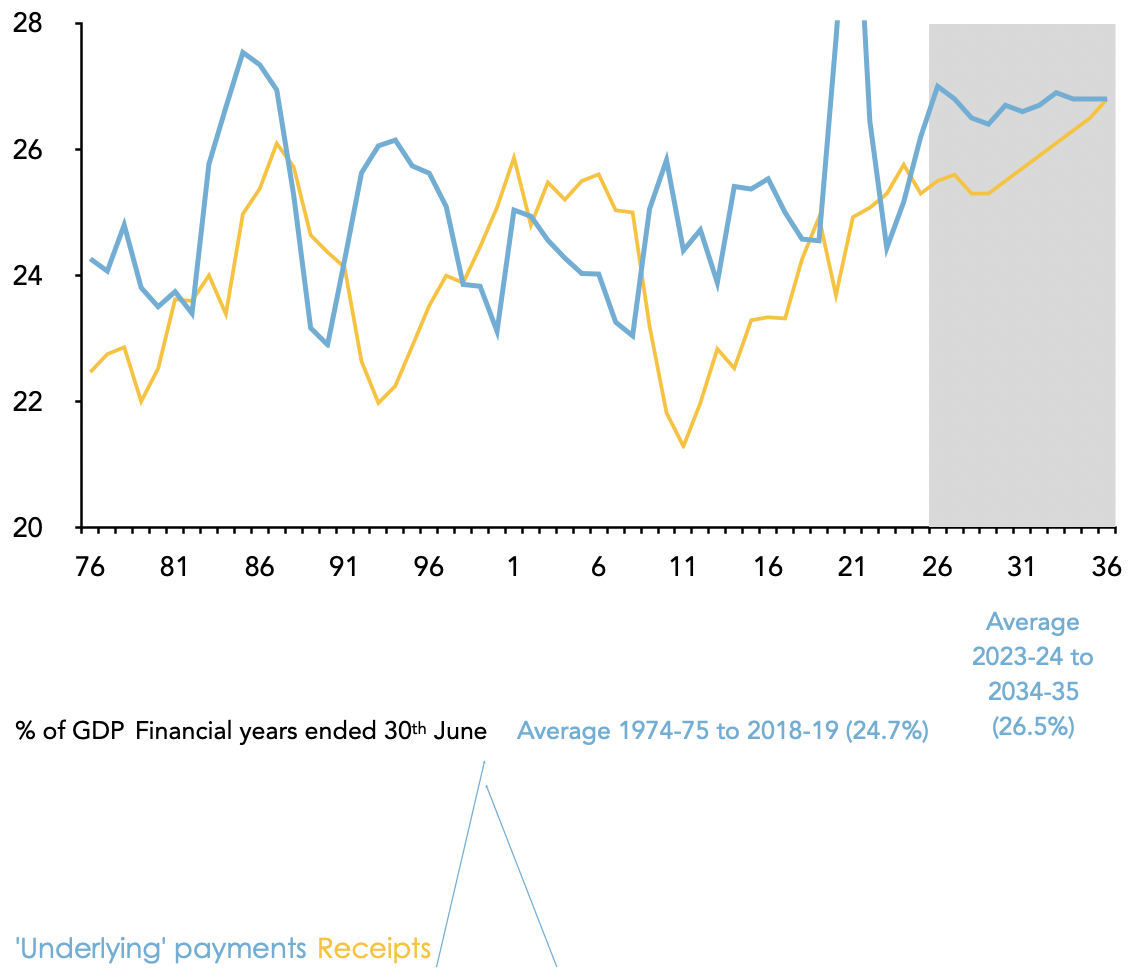

It has been evident since the last Budget of the former Coalition Government, presented by then treasurer Josh Frydenberg in March 2022, that federal government spending is likely to be permanently higher, by between 1½ and 2 percentage points of GDP, over the next decade than the average which prevailed between the end of the Whitlam years and the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Chart 1: Federal government cash receipts and ‘underlying’ payments

_Note: “_Underlying payments” excludes “investments in financial assets for policy purposes” (aka “off-budget spending” which are projected to average 0.7% of GDP over the five years to 2028-29, cf. 0.2% of GDP over the ten years to 2023-24. Source: Hon. Jim Chalmers and Hon. Katy Gallagher, 2025-26 Budget Paper No. 1, Statement 10: Historical Australian Government Data, 25th March 2025.

There are three reasons for that:

- first, the public clearly want more spending on health, aged, disability and childcare;

- second, there is a bipartisan consensus that, whether the public wants it or not, they are going to get more spending on defence; and

- third, because of the $600 billion increase in net debt since the onset of the global financial crisis, and the projected $391 billion further increase in net debt over the next decade, there is unavoidably going to be more spending on interest.

And it’s far from obvious that this additional spending can be offset by cuts to spending in other areas of the budget (although scrapping the obscene WA GST deal — which was most recently estimated to cost $60 billion over the 11 years to 2029-30 — would be a very good step in that direction).

So what could the treasurer contemplate, if he is serious about raising additional revenue, of between 1 and 2 percentage points of GDP, in order to pay for this additional spending and put the budget on a sustainable trajectory, in the fairest and least economically damaging way?

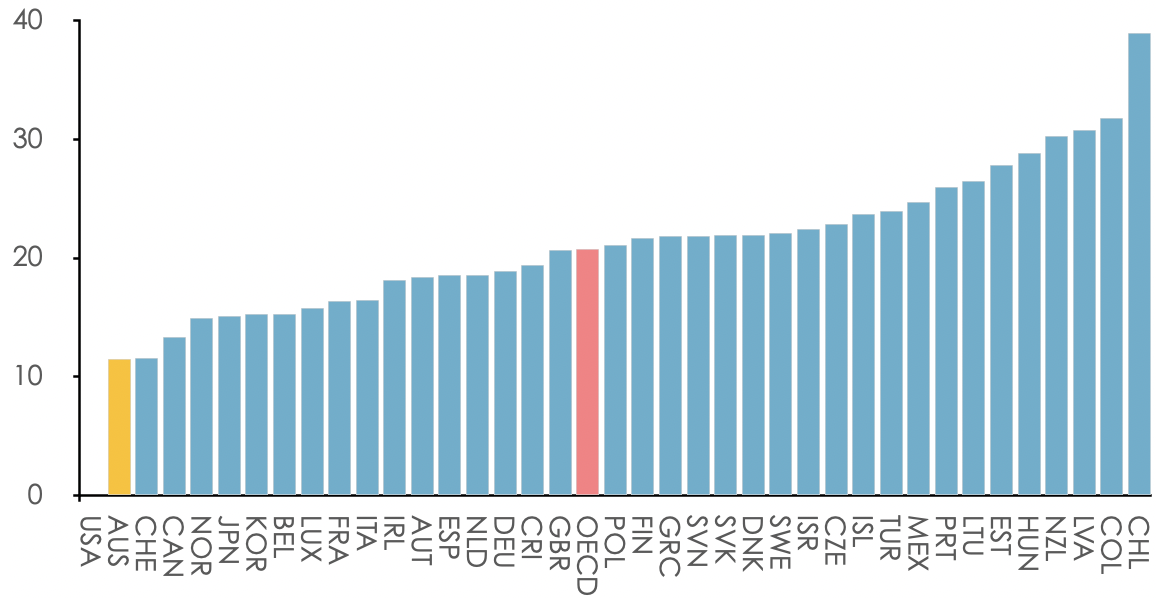

In principle, one of the first “cabs off the rank” should be an increase in the rate and a broadening of the base of the GST. Australia’s GST contributes only 12½% of total taxation revenue, less than every other OECD country (except the US, which doesn’t have a GST), and well below the OECD average of 20¾%.

Chart 2: GST (VAT) revenue as a percentage of total taxation revenue, OECD countries, 2022

Source: OECD, Consumption tax trends 2024.

Australia’s GST rate of 10% is (along with Japan’s) lower than all but two (Canada and Switzerland) of the OECD countries which have a GST-type tax, and well below the OECD average rate of 19.2%: 23 out the 37 OECD countries have standard GST rates of 20% or higher (although many of those countries apply lower rates to “essential” items like food and, more recently, energy). Australia’s GST only applies to 50% of total final consumption expenditure, less than in 26 of the 37 OECD countries with a GST, below the OECD average of 58%, and well below New Zealand’s 96%.

However, as a practical matter, no federal government is ever going to wear the political odium of raising the rate or broadening the base of the GST, and bear the financial burden of compensating up to one-third of all households for the impact of doing so on them, while state and territory governments get to spend the resulting additional revenue, as would occur under our present system which allocates all the revenue from the GST to them.

So the “nexus” between GST revenues and federal “untied” grants to the states and territories would need to be broken before this, otherwise highly desirable, reform, could be implemented.

There is one major objection to collecting more revenue from the GST – namely, that it’s potentially regressive, because lower-income households spend a larger proportion of their income, and hence would be proportionately more affected by an increase in the rate of GST than higher-income households.

That’s a legitimate concern. One way of addressing it, which is quite common in European countries where the standard rate of VAT is much higher than Australia’s GST, is to have lower rates on “essential” items. It’s also worth noting that many of the items currently exempt from GST in Australia, such as private health insurance premiums and private school fees, constitute a larger proportion of the spending of higher-income households than of lower-income ones – so broadening the base of the GST would not necessarily be “regressive”.

But in order to “sell” an increase in the rate and/or broadening of the base of the GST, it would seem sensible — as well as being justified on other grounds — to include some “progressive” tax reforms in any comprehensive reform package: that is, measures which have a larger impact on higher-income households than on lower-income ones.

In this context, it’s worth noting that, according to the latest available (2021-22) Taxation Statistics from the ATO, 47% of the income reported by taxpayers in the top tax bracket was in forms other than wages and salaries or interest, compared with 14% of the taxable income reported by taxpayers who weren’t in the top tax bracket. Equally notable is that income in forms other than wages and salaries made up just over 72% of the income reported by people aged 65 or over, as against less than 21% of the income reported by people aged between 18 and 65.

That’s significant, because income in forms other than wages and salaries — capital gains, dividends, rent, distributions from trusts and partnerships — is taxed at lower rates than identical amounts of income from wages and salaries or interest; and income paid out of superannuation funds in the “retirement phase” isn’t taxed at all.

So the concessional treatment of income in forms other than wages and salaries or interest disproportionately benefits higher-income and older households, at the expense of lower- and middle-income, and younger households.

And that, in turn, suggests that a “progressive” reform of the income tax system, justifiable in its own right, but especially as a counter-balance to an arguably “regressive” increase in the GST, would be to reduce the generosity of the tax treatment of these other forms of income, compared with that of wages and salaries or interest. That could be done, for example, by reducing the 50% tax discount on capital gains, curbing negative gearing, taxing trusts as companies, or taxing payouts from superannuation funds.

Alternatively, it could be achieved by adopting the schedular system used in Nordic countries under which income from “capital” is taxed at a flat rate with no tax-free threshold.

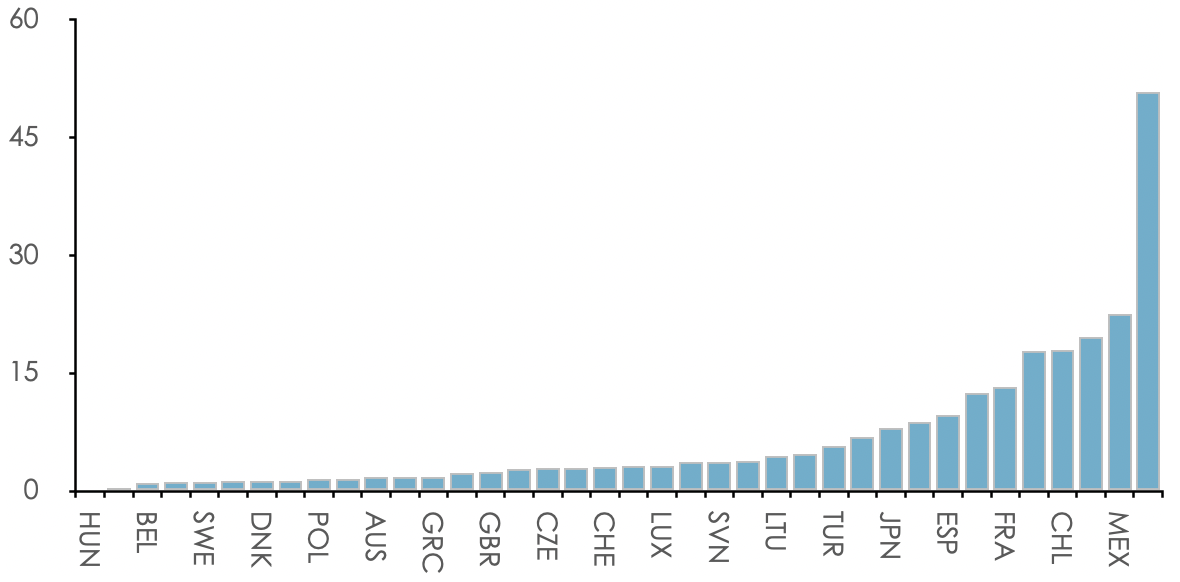

In order to make those changes more politically “saleable”, an appropriate quid pro quo could be a significant increase in the threshold at which the top rate of income tax becomes payable. Australia’s top personal income tax rate (of 47%, including the Medicare levy), is in the middle of the range for OECD countries. But the threshold at which it becomes payable — just 1.7 times average annual earnings — is very low by OECD standards, as shown in Chart 3.

Chart 3: Top personal income tax rate threshold as a multiple of average earnings, OECD countries, 2024

Source: OECD, Data explorer.

Depending on how much additional revenue was produced by reducing the concessional tax treatment of non-labour income and by raising the rate or broadening the base of the GST, it could be possible to reduce the marginal income tax rates paid by lower- and middle-income earners.

And the tax scales should be indexed for inflation, as they are automatically in 17 OECD countries. A particularly sensible suggestion is Westpac chief economist Luci Ellis' proposal that income tax thresholds should be increased by 2.5% (the mid-point of the Reserve Bank’s inflation target range) annually, so that when inflation is above (below) the target band, fiscal policy is automatically tightened (loosened), which would take some of the burden of responding to fluctuations in inflation off monetary policy and dampen swings in interest rates.

In addition to making a meaningful contribution to “budget repair”, and to improving the equity of Australia’s tax system, reforms along these lines could also assist the objective of improving Australia’s productivity performance, by increasing incentives to work (through reductions in tax on labour income) and to invest in income-generating assets rather than assets whose primary purpose is to produce capital gains (that is, speculation).

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.

Can you help Pearls and Irritations raise funds this month?

For the month of June Pearls and Irritations is running a fundraising campaign through the Australian Cultural Fund. Your donation will support the development of content for topics of particular of interest to Australia - Palestine, China, Climate Change and Immigration Policy and the development of a Young Writer’s Handbook to encourage new young writers.

Please make your tax deductible one-off donation here.