Inequality and inheritance taxes

June 5, 2025

With a few exceptions (such as Andrew Leigh, Nicki Hutley and Angela Jackson), “mainstream” Australian economists — including me — haven’t thought, spoken or written as much about the causes and consequences of increasing inequality as perhaps we should have done in recent decades.

International institutions such as the IMF and the OECD — traditionally bastions of “pro-market” economic policies — have in recent years come to recognise that increasing inequality has adverse economic and political consequences. Increasing inequality has undoubtedly been a contributor to some of the uglier political developments witnessed over the past decade in the US and Europe. And it has also been a factor in the increasing difficulty of building public support for (or even acceptance of) the sort of policies that “mainstream” economists typically advocate for in order to reverse the slide in Australian productivity growth – policies which are often widely seen as having contributed to increasing inequality.

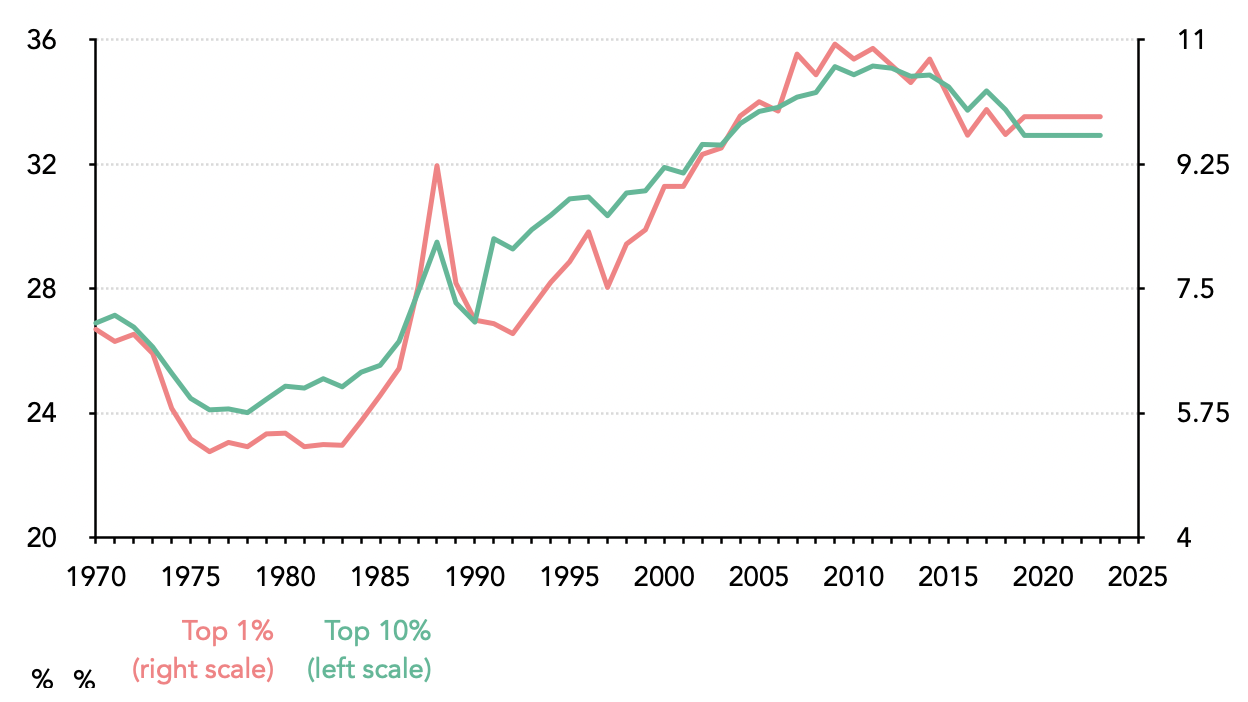

By comparison with most other “advanced” economies, Australia has done a reasonably good job in preventing the distribution of income from becoming more unequal. Indeed, the share of total household income accruing to the top 1%, or the top 10%, of households has actually declined over the past 15 or so years, after rising steadily from the early 1980s until the mid-2000s (Chart 1).

Chart 1: Share of Australian household income accruing to the top 10% and top 1%

Source: _World Inequality Database__._

That’s in no small part because, as the ANU’s Peter Whiteford has long argued, Australia’s comparatively progressive (at least with regard to income) taxation system, means-tested social security system and relatively high minimum wages have done a good job, by international standards, in moderating the impact of global and domestic market forces tending to make the distribution of income more unequal.

The share of household income accruing to the top 1% and top 10% of the Australian income distribution is less than that in any other “Anglo” country (New Zealand, Canada, the UK or the US), and less than in Spain, France, Germany or Japan. Indeed, the top 1%’s share of Australian household income is less than in ostensibly more egalitarian Sweden, according to the World Inequality Database.

However, the distribution of wealth is not only much more unequal than that of income — in Australia as in every other country — but has become more so in Australia over the past three decades (apart from some temporary dips in the late 2010s and early 2020s), as shown in Chart 2.

Chart 2: Share of Australian household wealth owned by the top 10% and top 1%

Source: _World Inequality Database__._

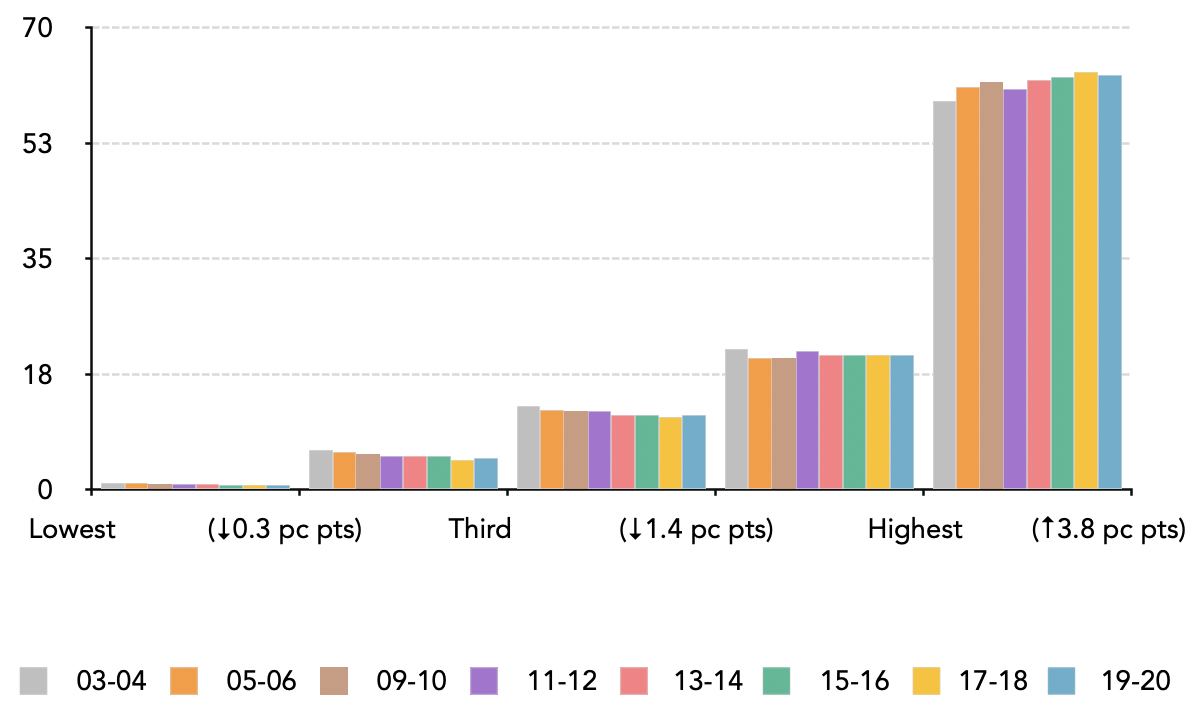

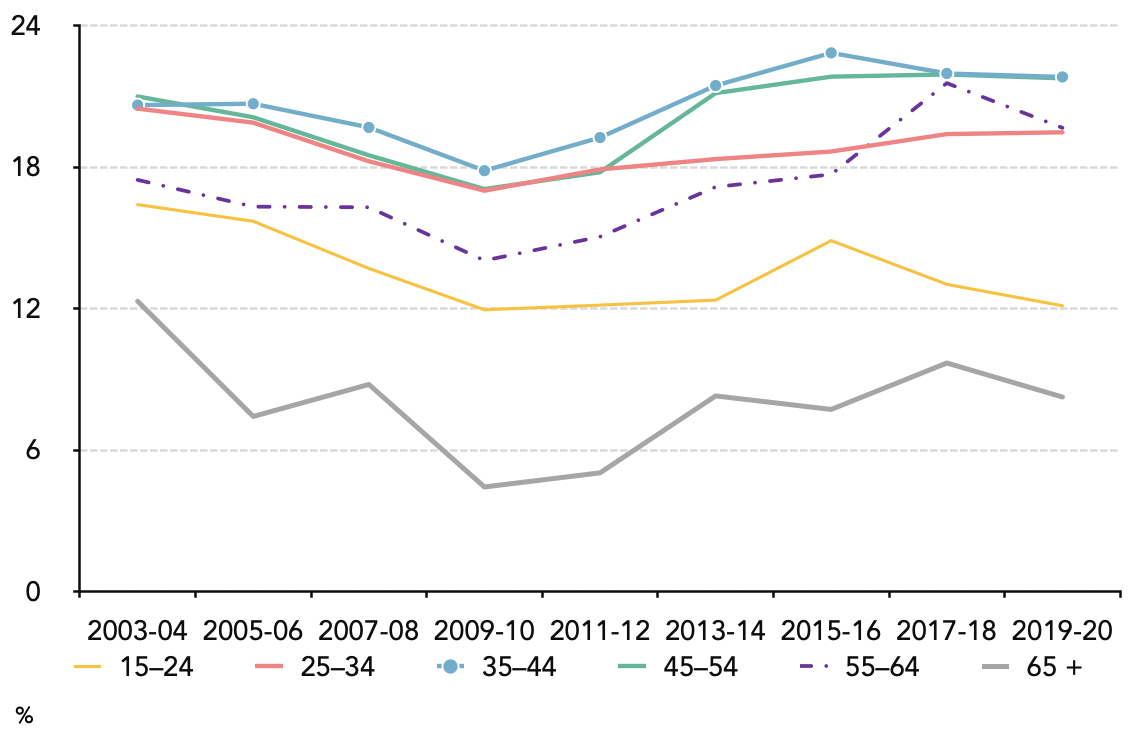

Data from the ABS’ periodical Surveys of Income and Housing, which are normally conducted every two years — but the most recent was in 2019-20 — shows that the share of total household net worth owned by the top “quintile” (20%) of households ranked by net worth rose from 59.0% in 2003-04 to 62.8% in 2019-20, ie by 3.8 percentage points, while the shares owned by the other four quintiles all declined (see Chart 3).

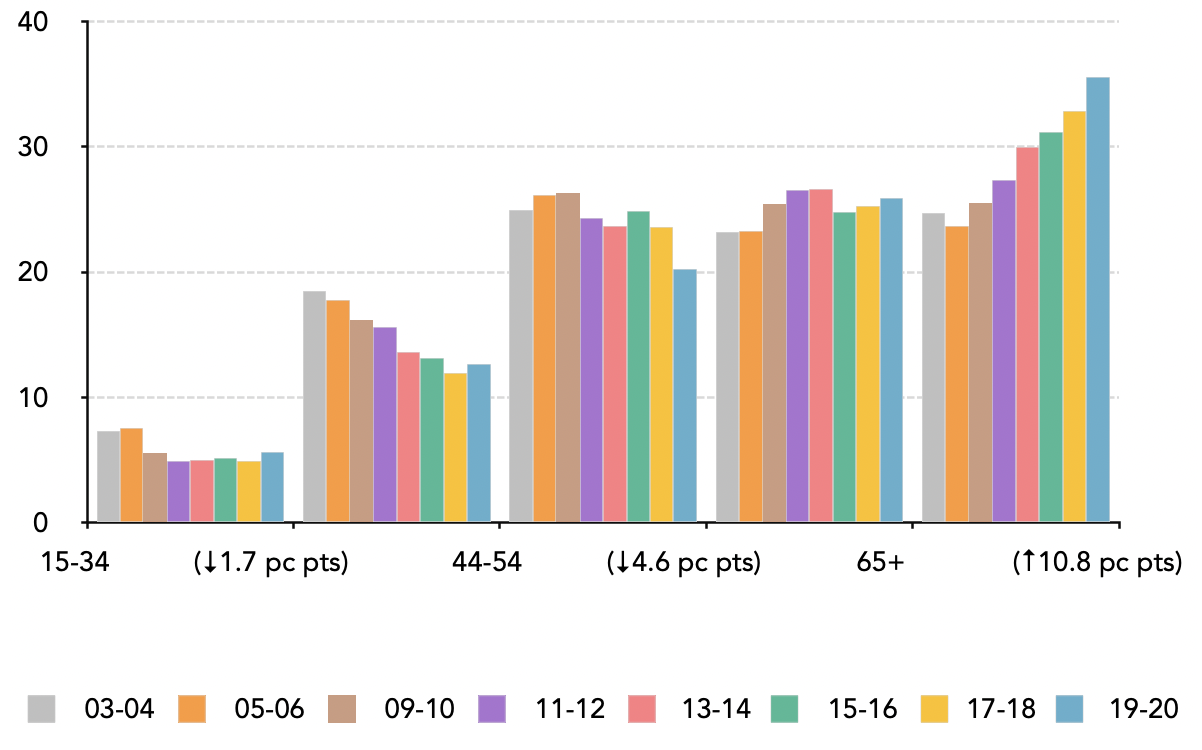

That may seem to be a rather small shift over 16 years. But the shift in the distribution of wealth is much more dramatic if viewed through an intergenerational lens – that is, by age group rather than by the more traditional net worth quintiles.

As shown in Chart 4, the share of household wealth owned by households, where the “reference person” (as the ABS now says, instead of the out-moded “head”) is aged 65 or over, rose from 24.8% in 2003-04 to 35.6% in 2019-20 — an increase of 10.8% percentage points — while the share of wealth owned by households aged 54-64 rose by 2.7 percentage points over the same period. These gains were at the expense of younger households: the shares of total household wealth owned by households aged 15-34, 35-44 and 45-54 fell by 1.7, 5.9 and 4.6 percentage points, respectively, between 2003-04 and 2019-20.

Chart 3: Shares of Australian household wealth owned by net worth quintile

% of total Net worth quintile 2019-20 and previous issues. Source: ABS, _Household Income and Wealth, Australia_,

Chart 4: Shares of Australian household wealth owned by age groups

% of total Age of ‘reference person’ Source: ABS, _Household Income and Wealth, Australia_, 2019-20 and previous issues.

It is, of course, to be expected that older households will, on average, be richer than younger ones, since they have had longer to accumulate income and generate wealth. And it would be surprising if the share of household wealth owned by older households hadn’t risen to at least some extent over the past two decades, given that older households account for a greater share of the population.

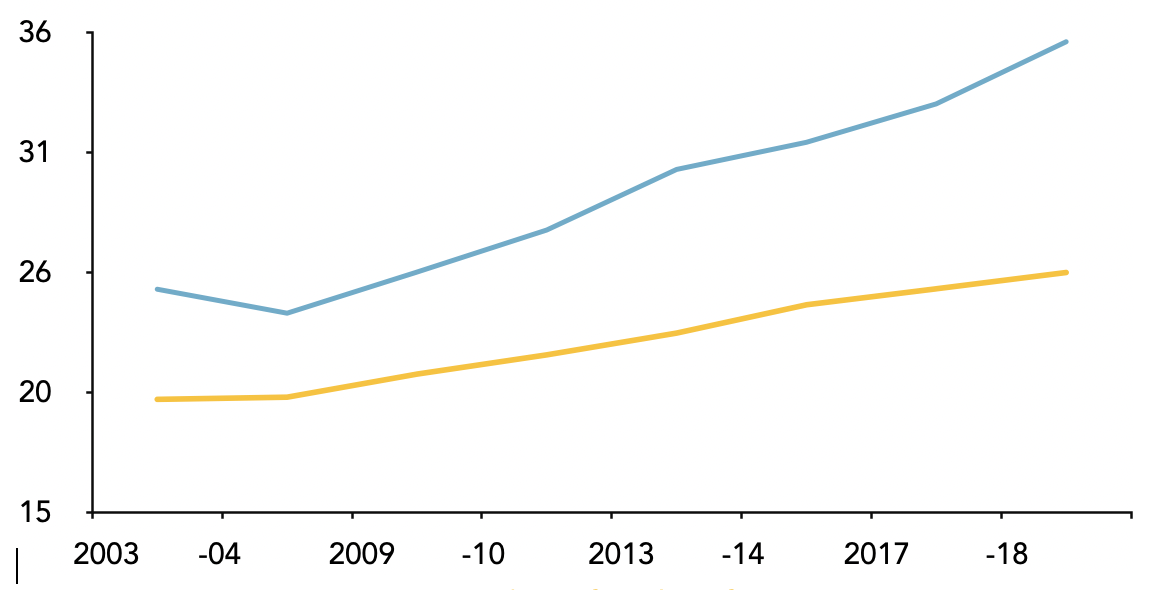

But the ageing of Australia’s population doesn’t go anywhere near fully accounting for the extraordinary increase in the share of household wealth owned by older households over the past two decades. As shown in Chart 5, the proportion of Australian households where the “reference person” is aged 65 or over rose by 5.6 percentage points between 2003-04 and 2019-20 – barely more than half the increase in the share of household wealth owned by those households.

Chart 5: Proportion of Australian households aged 65 or over vs share of Australian household wealth owned by households aged 65 and over

% of total (Blue) share of household wealth % 24.835.6. / (yellow) share of number of households % 19.925.5

Financial year ending 30th June. Source: ABS, _Household Income and Wealth, Australia_, 2019-20 and previous issues.

Rather, the main reasons for the striking increase in the inequality of the distribution of wealth across age groups have been that older households own a rising share of the two assets which account for most of household wealth — namely, property (56% of total household assets) and superannuation (33%) — which have been growing in value, while younger households owe most of the liabilities which are offsets to wealth, namely mortgages (90% of total household liabilities) and student debt (3%), and which have grown at a faster rate than assets over the past two decades.

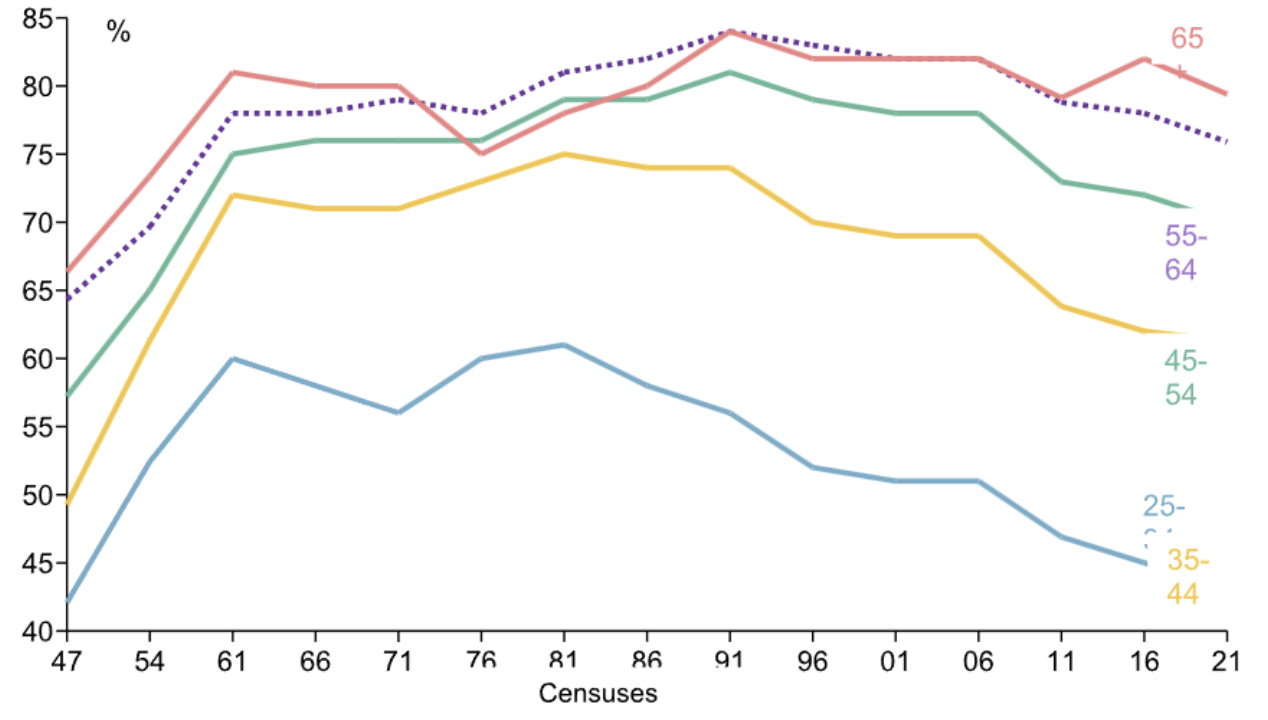

A particularly important contributor to increasing inequality in the distribution of wealth across age groups has been the decline in home ownership rates among younger households. Australia’s home ownership rate declined by 6.6 percentage points from its peak at the Census of 1966 to 65.9% at the most recent Census in August 2021.

But that conceals very different trajectories across different age groups. As shown in Chart 6, the home ownership rate among people aged between 25 and 34 fell from a peak of 61% at the 1981 Census to 43% in 2021, only one percentage point above where it had been at the first post-War Census in 1947. The home ownership rate among 35-44 year-olds fell from 75% in 1981 to 61% in 2021, 11 percentage points lower than it had been at the Census of 1954. Even among 45-54 year-olds, the home ownership rate of 70% at the 2021 Census was down by 11 percentage points from its peak 30 years earlier, and 5 percentage points lower than it had been 60 years previously.

Chart 6: Home ownership rates by age group at Censuses, 1947-2021

Sources: ABS, _Housing: Census_, 2021 and previous issues; Judy Yates, _Submission to the Senate Economic References Committee on Affordable Housing_, 2015; Rachel Clun,

‘Mortgages in retirement triple, outright ownership halves for most age groups’ _The Age_, 17th July 2022.

To some degree, the decline in home ownership rates among people in their 20s and 30s today, compared with people at a similar stage of their lives in the immediate post-war decades, reflects differences in lifestyle and career choices between Generations Y and Z and their Baby Boomer parents or grandparents. Not too many of the former are getting married and having children, as the overwhelming majority of their parents and grandparents did at similar ages; and most of them have spent longer in the education system, and thus started working, earning, and saving, later in life than their parents and grandparents.

But a far more important factor has been the decline in housing affordability, as encapsulated by the dramatic increase in dwelling prices as a multiple of whatever measure of income you choose to use, or that it now takes someone on the median household income almost 11 years to accumulate a 20% deposit on a median-priced dwelling, almost three times as long as in 1984.

Another important factor has been the series of conscious decisions by successive Australian Governments to allow older people to pay less tax on any given amount of income than younger people, either explicitly on the basis of age (as with the Senior Australians’ and Mature Age Workers’ Tax Offsets introduced by the Howard Government in 2001 and 2005, respectively), or as a result of taxing particular forms of income (such as capital gains, dividends and payments out of superannuation funds) which account for a much larger share of older people’s income than of younger people’s, at lower rates than equivalent amounts of income from wages and salaries, which make up the bulk of younger people’s incomes.

Thus, in 2019-20, households where the “reference person” was aged 65 or over made up 25.5% of the number of households, earned 16.7% of total household income, and owned 43.4% of total household wealth – but paid just 7.4% of total personal income tax (Chart 7).

Chart 7: Average tax rates by age group

Source: ABS, _Household Income and Wealth, Australia_, 2019-20 and previous issues.

What could be done to reverse this trend of increasing inequality in the distribution of wealth across age groups, if governments wanted to do so?

The most important thing would be to reverse the slide in home ownership among younger age groups, given the important role which home ownership has traditionally played in allowing a broad spectrum of the population to participate in accumulating wealth and, in particular, offering some form of security in retirement.

In recent years, governments of both major political persuasions have adopted the view that the best way of reversing the deterioration in housing affordability for would-be home-buyers is by boosting the supply of housing.

By contrast, both major political parties have been extraordinarily reluctant to back away from policies which inflate the demand for housing (over and above that intrinsically associated with growth in and changes in the structure of the population).

On the contrary, the number and value of programs such as cash grants and stamp duty concessions to first-home buyers, shared equity schemes, and deposit guarantee schemes has continued to increase – notwithstanding over 60 years of evidence which overwhelmingly demonstrates that such programs serve only further to inflate house prices. Indeed, that was explicitly acknowledged by the leaders of both major political parties during the recent federal election campaign, in which both of them proposed policies which would boost the demand for housing, and in which both of them stated that they wanted housing prices to “keep going up” (at least they were both being honest about that!).

It would also be helpful, from the standpoint of curbing the increasing inequality in the distribution of wealth across different age groups, if governments were to reduce the concessionality of the tax treatment afforded to the types of income which disproportionately accrue to older and wealthier taxpayers, in particular capital gains and dividends, and earnings in and payments out of superannuation funds.

Finally, governments could consider the re-introduction of some form of taxation of inheritances or bequests – especially given the scale of wealth which is likely to be transferred between generations as the Baby Boomers pass away, which some estimates put at almost $5½ trillion.

Although that would inevitably be almost immediately depicted as “socialism” (or worse) by politicians and commentators across the spectrum, Australia is actually something of an outlier among OECD countries in not having any form of inheritance taxation.

In particular, both the United States and the United Kingdom — whose tax systems are commonly used as points of comparison for Australia’s — do both levy taxes on large estates; and neither Ronald Reagan nor Margaret Thatcher, both of whom undertook significant tax reforms during their periods in office, saw fit to abolish them. Nor, for that matter, did Sir Robert Menzies during his 19 years as prime minister of Australia.

Ironically, the abolition of Australia’s federal death duties was precipitated by Labor icon Gough Whitlam, who promised to do so in his doomed 1975 election campaign (echoing a similar move begun at the state level by Queensland’s Joh Bjelke-Petersen) – which prompted Malcolm Fraser to make a similar promise ahead of the 1977 election, that he then implemented after winning it by a similar landslide to his victory in 1975.

The US Federal Government collected US$32 billion in revenue in fiscal year 2024 from estate taxes levied on estates valued at over US$13.6 million (the threshold is indexed annually for inflation), or about 0.2% of all estates; while the British Government collected £7.5 billion from inheritance taxes levied on estates valued at over £325,000 in 2023-24 (the Office for Budget Responsibility expects this revenue to double by 2029-30).

Given that some 64% of inheritances in Australia go to people aged 55 or over, most of whom are already in the upper half of the wealth distribution, a tax on inheritances of over (say) $3 million — with an exemption for surviving spouses or partners, and perhaps with some incentives for bequests to registered charities — would likely make a useful contribution to curbing the otherwise seemingly inexorable upward trend in the concentration of wealth in older and wealthier hands.

Increasing inequality in the distribution of income and wealth has adverse economic and political consequences. Economists should be doing more to bring those to the attention of the Australian public, and to propose politically workable solutions.

(Note: this article is based on a talk given by Saul Eslake to a Business Breakfast in Hobart on 16 May 2025, hosted by the Tasmanian Division of the Salvation Army for the launch of their annual Red Shield Appeal. A podcast of that talk, and a copy of the slides accompanying it, can be viewed here).

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.