Nuclear subs taking on water

June 17, 2025

There is every reason for Australia to jump on board the idea of having a review of its AUKUS defence policy.

The America First initiative is an opportunity to get out of a deal that was bad from the start, but it is getting seriously worse.

It was, as any number of ex-prime ministers and foreign ministers, Labor and Liberal, tell us, a very bad deal, in which all the risk fell on Australia, and the goodies on offer would come too late, if indeed they came at all. The risk that they would never arrive has been increasing, although a failure to deliver on the part of either the US, or later, Britain, would not, in the very unequal deal, amount to a breach of contract. The US is bound to deliver only if some future US president decides the US has enough nuclear submarines of its own.

Anthony Albanese and particularly his deputy, Richard Marles, were fools to adopt the Morrison plan.

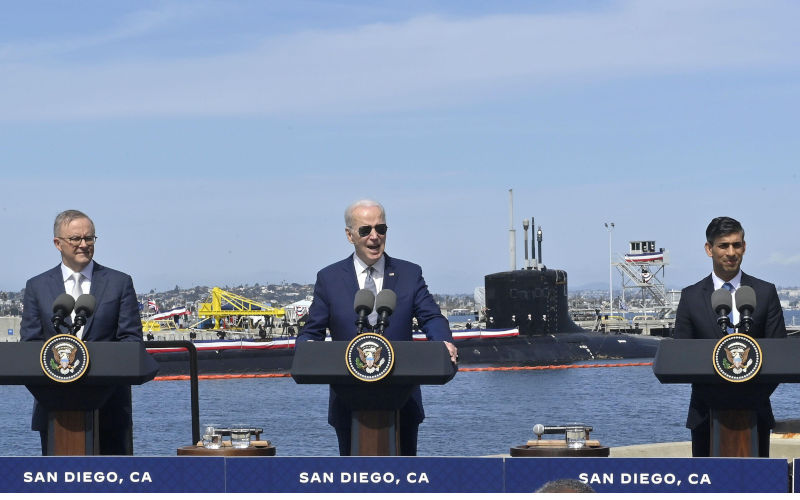

The arrival of President Trump has added new layers of uncertainty to a deal that was already very iffy. Joe Biden, who signed the deal on behalf of the US, was at least committed to attempting to maintain American dominance in the western Pacific, even if outsiders considered that the rise of China made that impossible. Biden’s manoeuvrings attempted to lock Australia in on the deal by extending AUKUS ties with Australia, including weapons storage and troop training. Now there is not only the problem of guessing what Trump thinks of US commitments, but how long those commitments will continue, because Trump frequently changes his mind and lets allies down. Consider, for example, his relationships with Ukraine, with Europe and in the Middle East. And with Canada, or Denmark.

Trump has also produced a new hostility to Australia’s economic interests which undermines America’s capacity to claim to be an alliance partner or friend. Australians no longer share the values that Trump, and Trumpism, represents. Increasingly, Trump acts as if all his old allies, except Israel, are now both his economic and his military enemies. Australian officials think we maintain a core of personal relationships with American diplomats and military personnel that transcend the eccentricities and abrupt shifts by the president and his cronies. But such relationships do not seem to have worked, except in oozing charm on a very susceptible Marles. (Nor have other countries, such as Britain, Germany, France or Canada found that similar deeply embedded relationships have tempered the problems of Trump.)

A new circumstance is that it is becoming clear that the US is using AUKUS, and its suddenly announced “review” of its AUKUS commitments, as a lever with which to press Australia to increase its defence expenditure. Indeed, that may be the whole purpose of having the review. There is nothing new as such in US pressure, particularly from Trump, to increase defence spending, preferably up to 4% of gross national product. But the linkage of the two, together with the implications that Australia has been freeloading on the US on defence matters, is a galling inversion of the truth.

Over the years, indeed, Australia has been too much an ally of the US, joining it in all sorts of absurd adventures (and failures), not in our national interest, believing we should do them to maintain credit with the US. Such partnerships have cost us much more than blood and treasure, substantial as that has been. It has also diminished our reputation in the world and in our neighbourhood, with many nations regarding us as no more than America’s poodle, unable to act independently even when its interests are manifestly different from those of America. Our slavering loyalty has not been rewarded – as witnessed when America stole our markets after Scott Morrison provoked China to the point that it punished Australia, not America, by banning imports of Australian goods.

Moreover, our AUKUS commitments are neither in financial nor strategic terms much, if at all, to Australia’s benefit. From the US point of view, the deal locks Australia in as a very special ally with no, or next to no, right of independence of action. It is America, not Australia, which decides whether and when submarines come, and the US, for that matter, seems unable to honour its promises, even if it wanted to. Australia is paying through the nose, with no guarantees, and has almost no contractual rights or independence of action.

The freeloading argument must be evaluated against the fact that the US-Australian alliance has involved massive Australian purchases of US military goods, in part for the explicit purpose of having virtually interchangeable equipment and military doctrine. Most equivalent countries, particularly in Europe, are nowhere as dependent on US military technology (and the flow of dollars to the US that represents).

Nor does evaluation of the costs and benefits of the relationship pay any regard to the usefulness of American bases and intelligence capacity based in Australia.

Many Australians do not recognise what an unequal relationship the partnership involves. One reason for this is that much of Australia’s defence and intelligence establishment, including within academia and the bureaucracy, has been captured by the US view of the world. Many of our politicians, generals, admiral and air-vice marshals, and many of our intelligence boffins have effectively transferred their loyalties to the US, and America’s view of how the alliance works. It is not a selfless conversion.

The Pacific Ocean is choked with the traffic of consultancies, cross-postings, post-retirement jobs, and a revolving door of appointments, including handsome jobs in defence industry to people involved in approving tenders of billions of dollars. It is a market full of potential for corruption and conflict of interest, a risk from the lack of integrity controls, the lack of service, bureaucratic and political will to enforce the pathetic ethical obstacles that exist and the poor example of senior staff. Put bluntly, many of those involved in this game lack integrity, or obvious (patriotic) focus on Australia’s national interests and the public interest. For at least 50 years, I have argued the need for some serious rules on this, but to no effect.

There’s another new reason for an independent and open review. Our American friends have come to think that our AUKUS signature precommits us to fight alongside the US if the US goes to war with China over Taiwan. Otherwise, it would not dream of selling us its old subs. Australia has never publicly committed itself to any fight over Taiwan, and, 50 years ago it would have been unthinkable. Obviously, we would deplore a less-than-peaceful reunion, but that does not mean that we would go to war over it, any more than we would go to war to defend the human rights of the people of Gaza when they are being massacred by the Israeli state. At most we belatedly borrowed the “strategic ambiguity” line once used by the US, by indicating that we would not decide how we would react to an invasion until after it happened. Sort of like the US commitment to the defence of Australia under the ANZUS Treaty.

Willy nilly, the US, which now seems determined on war if there is an invasion, is pressing for a definite Australian commitment. Many in our military establishment now seem to take it for granted that we would be involved, and our intelligence establishment, many of them shills for Taiwan when moonlighting from their US duties, work long and hard to press it as if it were an alliance obligation, though whether to the US or Taiwan is never made clear. Our hardheads might have strong sympathies for Taiwan, but do not want to get involved because their research shows that the US cannot win a war over Taiwan. Nor can we, but it would deliver us a higher class of determined and vengeful enemy. The Chinese may have failed to notice Australians in Korea and were probably highly amused at how we got bogged down in losing struggles in Vietnam, the Middle East and Afghanistan. But the merest Australian assistance to the US would provoke serious retaliation we do not need and make Australia an equal partner with the US in any vengeance doled out. We should not throw our young men and women into a conflict we cannot win.

America, or Trump, or both can afford to experiment with threats of war, if only to mess with China’s head, or to give the impression that they are entrenched in Asia forever, with no intention ever of retreating. We live here, and we, on our own account, want to continue to be an active player on the scene, including as a major trading partner with neighbours including China, Japan, Korea, Indonesia, Vietnam and India. We can trade with each other, improve our social, cultural and educational relationships and tourism and have free exchanges of opinions and ideas, including criticism of their systems of government. China seems to do this with most of the world, and its record of invading other countries is markedly better than ours or (pretty much the same thing) the US. If war comes, it will be at the US instance, not China’s.

There is another argument for an independent and open Australian review. We have never had a proper debate on the AUKUS relationship, or even of the suitability of ANZUS arrangements for the present day. A debate is not a matter for a few inside experts, not a jamboree by a few retired insider politicians. It is one for the community, including the third of the nation which does not accept the consensus of insiders and directors of arms companies. Their credibility is low, and some of them, however involved in the defence gravy train, are not closely involved in Australia’s image in the world. I would rate the current knowledge, the political instincts, and the feel for the thinking of ordinary Australians found in Paul Keating, or Malcolm Turnbull, or Gareth Evans against any number of former politicians now in cosy diplomatic jobs in London and Washington. And that’s regardless of the number of “high level briefings”, site visits, golf games and to the fine mind and communications skills of a Richard Marles.

It reflects seriously on the prime minister that he never encouraged a widespread public debate, or for that matter, a population well educated on the issues at stake. Perhaps he felt insecure when he had a narrow majority, and a crossbench generally hostile to the comfy consensus of the Labor and Liberal parties. But he is not in that position now and must feel that he has nothing to apologise for.

Compulsive secrecy, efforts to control the extent of the debate and the information to which it is allowed access, will not be enough to unite the population around what he quaintly called “a progressive patriotism where we are proud to do things our own way”.

At the press club on Tuesday, Albanese even sketched out how it could be — should be — done. He talked about popular frustration, “drawn from people’s real experiences, the feeling that government isn’t really working for them".

“To counter this, we have to offer a practical and positive alternative… We want a focused dialogue and constructive debate that leads to concrete and tangible actions… Change that is imposed unilaterally rarely endures. The key to lasting change is reform that Australians own and understand. Reform that serves a national purpose and the national interest. Change that empowers and engages people, with a sense of choice and urgency. Change that generates its own momentum and builds its own staying power.”

This is not how Albanese has hitherto managed the defence debate, or the argument about Australia’s place in the world. But he is right about the need to bring the public along. He must bring a new personality, a new attitude and a new confidence in the common sense of Australians. Otherwise he won’t be promoting a society Australians will clamour to defend.

Republished from The Canberra Times, 13 June 2025

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.