Scrubbing away the bloodstains, tipping out the truth

June 30, 2025

Lit lovers argue who first said “History is written by the victors”. It’s sharp enough to belong to Churchill, though earlier and longer versions come from politicians in the US and Germany – including fascist Hermann Göring.

The dictum is favoured by Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto. The disgraced former general has hired 113 wordsmiths and 20 editors to keyboard his Rp 9 billion ($850,000) version of the past, all within two months.

August 17 is always a big day for Indonesia’s 285 million citizens; this year, the show will be prodigious, marking the 80th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

The Brits do coronations – Indonesia goes brasher with fireworks, bunting, robot soldiers, clichéd speeches and enough flags to clothe the triumphs and mask the tragedies of a nation that calls itself a 25-year-old democracy, though foreign autonomies reckon it’s flawed.

The Republic is slipping back to the 55 preceding years of autocracy because democracy is “tiring, very costly and very messy”, according to Prabowo.

The heaviest splash on 17 August will come with the publication of Indonesia Dalam Arus Sejarah (Indonesia in the flow of history), a revision in 10 volumes – each of 500 pages.

There’s plenty to write about; the stories of the archipelago before the arrival of people are gripping enough for little is certain and much is contested. The first humans probably came from the Arabian Peninsula heading towards India:

“The descendants of this first wave arrived in what is now the Indonesian archipelago around 50,000 years ago. At the time, the Malay Peninsula, Borneo, and Java were still connected as one landmass called Sundaland. Descendants of this group continued to wander to Australia.” Other experts give earlier dates and different routes.

Molecular biologist Dr Herawati Sudoyo said modern Indonesians like to label people as pribumi (native) or pendatang (foreigners): “This dichotomy often creates racism and tension between groups in society.”

Indeed – and this is where the new versions collide with the survivors of the harrowing wrongs.

The books will adopt “a more positive tone towards each president, highlighting milestones such as Indonesia’s economic development under Soeharto and infrastructure expansion during the administration of Joko ‘Jokowi’ Widodo”.

In brief, a story stitched to squeeze a political agenda into the combat boots of those in power.

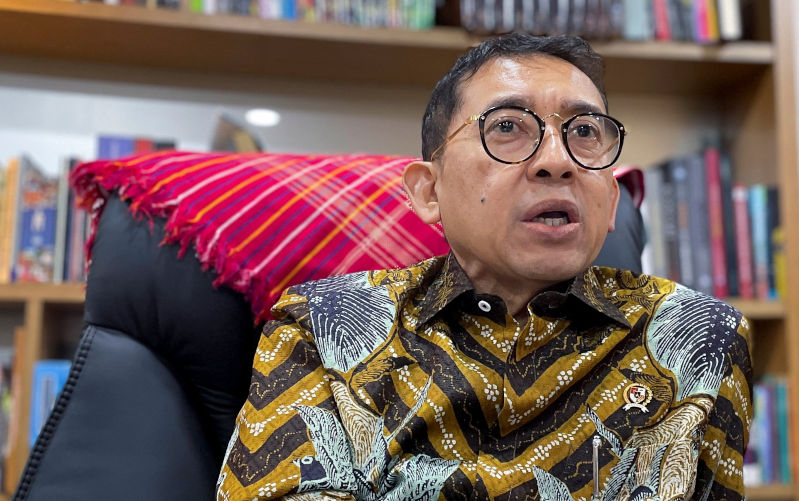

That’s the aim of Dr Fadli Zon, the Minister for Culture who is driving the project.

Unlike many other department heads, he’s not from the military – though he’s doing its bidding. He was educated in the US through an American Field Service Scholarship, and in Britain at the London School of Economics and Political Science, an institution famous for producing left-wing thinkers.

Fadli is not one.

A former activist-journalist turned politician and one-time critic of Jokowi, he swapped horses when he foresaw a changing political landscape. In 2015, he met Donald Trump, and in 2018 he allegedly tweeted:

“If you want us to rise and be victorious, Indonesia needs a leader like Vladimir Putin: brave, visionary, intelligent, wise, not too many debts, not clueless.”

Climbing the ladder also meant trampling those below – in this case the 11 million ethnic Chinese minority, always an easy mark for populists; few are Muslim in a nation where 87% follow Islam. The Chinese are smart in business; they stick together and work hard, so they’re often tagged as cheats and exploiters.

Indonesia’s long history of racism boiled over in May 1998 when its second president, Soeharto, quit after 32 years of autocracy; there was chaos in Jakarta and elsewhere with Chinese shops trashed, people killed and women sexually assaulted and mass raped.

In a TV interview, Fadli denied the events happened because no-one was brought to trial. Like Trump, he uses outrageous statements to grab attention.

The Jakarta Post opined “that the mass rapes that … ultimately led to the fall of then-authoritarian president Soeharto, are thoroughly documented and must not be removed from history for whatever reason".

“At that time, amid a series of demonstrations demanding reform, violence and civil unrest escalated … This period tragically resulted in over 1200 deaths, and at least 52 people, predominantly Chinese Indonesians, were victims of rape.”

Later Fadli tangled reason trying to explain that his comment “specifically highlighted the need for precision and an academic framework of caution in the use of the term ‘mass rape’, which can have serious implications for the collective character of the nation and requires strong fact-based verification”.

Requests to interview Fadli for this story have been ignored.

Queensland Uni doctoral candidate Muhammad Ammar Hidayahtulloh said denial of the mass rapes added to “ways in which Prabowo’s government continues to erode the democratic political system… rewriting history without a transparent and participatory mechanism, for example through public consultation, especially with victims.”

If the mass rapes can be deleted from Fadli’s revisions, what else can be trashed?

The 1965-66 killing of maybe half a million or more real or imagined communists in a Soeharto-orchestrated genocide was exposed by Australian academic Dr Jess Melvin as (according to the CIA) “one of the worst mass murders of the 20th century”.

There have been 67 other outrages since then — like the 1984 _petrus_ extrajudicial public executions of crims and dissidents, through the East Timor Referendum of 1999, religious conflict like the co-ordinated 2000 Christmas Eve bombings, the Bali bombings of 2002, the assault on the Australian Embassy in 2004 — and many more.

Are these bloodstains to be fully recorded in Fadli’s histories – or will they be footnoted as aberrations in the Republic’s growth? And where will Australia fit in – a supporter of decolonisation through the unions’ Black Armada campaign?

Unless there are leaks, we won’t know till the books are published; debate about content will be academic.

The national literacy rate is above 98% but Central Connecticut State University research ranked Indonesia 60th out of 61 countries for interest in reading. About 70% of students have low literacy skills.

During the 32 years of Soeharto, writers were regarded with suspicion. Their books, signed off by censors, were locked behind counters, like the way smokes are sold in Australia today.

Fadli’s legacy will be thousands of unopened copies of Indonesia Dalam Arus Sejarah moulding on the shelves of government offices to help talking heads look learned.

They’d get more viewings on TikTok.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.