The cultural and linguistic roots of protest in China

June 14, 2025

In 1760, the newly established Qing Dynasty was looking to expand Chinese territory by claiming the region of Xinjiang. Many Chinese intellectuals and scholars opposed this.

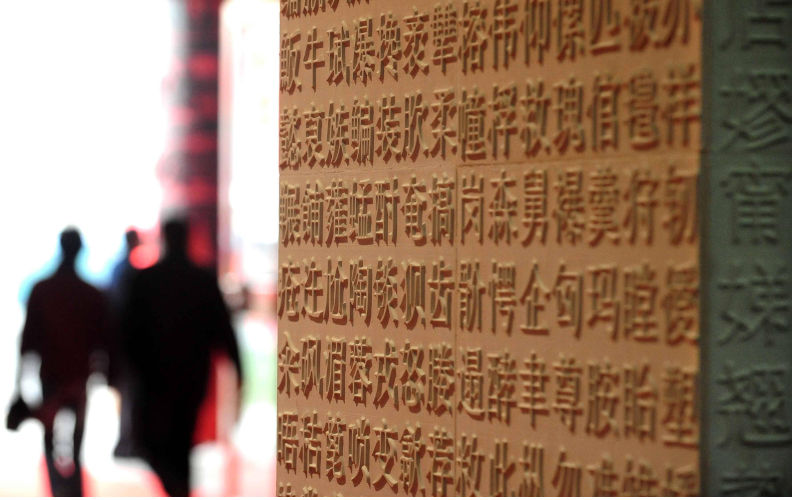

One manifestation of this opposition was expressed through the Imperial Exams of that year. When the exam answers were collected to be graded, it was found that a large number of candidates had colluded to include anti-war rhetoric in their answers. An examination of Chinese social media shows that subtle forms of protest continue to this day. The form of protest and the targets of that protest reveal how little conventional Western views of China have to with the reality of its people, its governance and how they relate to each other.

Homophones are a common source of humour in Chinese. This is fuelled by their sheer number. There are 400 basic syllables in Chinese (ma, ni, la) expanded to the use of 1600 expanded syllables through the use of four tones (mā má, mǎ, mà). There are however many thousands of words and characters which in turn lead to occasional confusion and opportunities for bemusement.

Chinese protest draws on this for political satire. The homophone “he xie”, for example, could mean 和谐 (harmonious) or it could mean河蟹 (river crab). As Chinese censors will sometimes say that censured materials have been “harmonised”, Chinese netizens will refer to an article that has disappeared by saying it has been “river crabbed”. As the possible homophones (and opportunities to use them) are endless, this leads to a constant cat and mouse game between Chinese netizens and censors.

Protest also draws on Chinese historical allegories to express disquiet. There were many reasons why COVID Zero eventually ended in China but a major one was the age-old issue of corruption. Some government bodies and companies were running COVID tests where they were not required in order to profit from them. One Chinese netizen remarked that it was as if the Qing dynasty dragon that produced rain was also selling umbrellas. Most Chinese people would recognise this allusion and understand what was being said. The skill of drawing on Chinese history in making the allusion increases the potency of the criticism, rather than diminishing it.

While direct opposition to the government may lead to issues for the netizen involved, direct opposition in any form also represents a cultural faux pas in Chinese society. The Chinese, like many Asians, avoid direct conflict. In a culture like China, there is a danger that conflict will break down the means by which all matters are progressed — relationships — and if that happens, no further progress can be made.

Confucianism also lays out codes for interactions between different hierarchies in society, ones that emanate from the relationship between a parent and child. The child can gently remonstrate with the parent if they disagree with their decision, but if the parent is unwilling to change their idea the child should accept this as the stability and harmony within the family structure is more important than a passing disagreement.

This notion is also extended to relations between the people and the government. Subtle forms of disagreement can be permitted, and in the right circumstances are successful, but they should never amount to a threat to the stability and harmony of the country.

An understanding of China that takes into account its own history, language and culture as opposed to judging it by Western standards should lead to a better understanding one of the world’s two superpowers. Given China’s economic, political and military significance this is of crucial importance.

Perhaps, though, we should also consider coming to understand something of China as an opportunity to enrich our understanding of the ways human beings live and relate to each other. This understanding, we might consider, may lead to a better understanding of life on this fragile, wondrous planet.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.