Why the world needs renewable food

July 14, 2025

The future well-being and survival of civilisation rests upon a single, fragile assumption: that there will always be enough food.

If the assumption fails, even in part, catastrophe will sweep the globe in the form of regional famines, tsunamis of refugees, the collapse of nation states, civil and international wars. Any history book can tell you as much – only now we have eight times the population that endured these horrors in the past, multiplying the risk eightfold.

Food is the blind spot of almost every government on the planet. They just assume there will always be sufficient to keep society going, despite the fact that, in two world wars, millions starved in Europe and Asia. They are deeply ignorant of the tottering edifice that is modern industrial agriculture, or its frailty in the face of resource exhaustion, eco-collapse, global poisoning, global heating and geopolitical upheaval.

Climate: Taking just one of these factors, a new paper in _Nature_ estimates that climate-driven harvest losses will knock 18%-41% off the average person’s nutritional intake by 2100, with the worst effects among the poor and people living in the tropics. However, successful adaptation by farmers in key foodbowls could offset these losses by up to a third. (Harvest losses in 2100 are estimated at 14-28% for wheat, 12-28% for corn, 22-35% for soybeans and >6% for rice.)

Agriculture is vulnerable to the droughts, floods, storms, heatwaves, fires and other weather impacts of a heating planet. However, the modern food system also churns out 30% of the greenhouse gases which are heating the Earth and thus makes a major contribution to its own demise.

Soils: Every year farming dislodges 24 billion tonnes of topsoil, which is lost into rivers and blown away by wind, and ultimately winds up on the ocean floor, where it will never grow food again. This amounts to three tonnes of soil lost to feed every person on the planet, every year: for example, just feeding you today will cost the Earth 8.2 kilos of lost soil. Modern agriculture is an unsustainable machine that destroys the very resources on which it depends.

Farming doesn’t just lose its soil, however. It also degrades what’s left. Many people don’t realise that the modern high-yield cropping systems that fill our supermarkets are in reality a form of mining: the use of 180mt of fertilisers and 5mt a year of pesticides over time strips the soil of precious micronutrients and nutrient-cycling organisms. The result has been a serious decline in nutrition worldwide along with a rise in diet-related disorders like heart disease, cancer and diabetes – the big killers of our time.

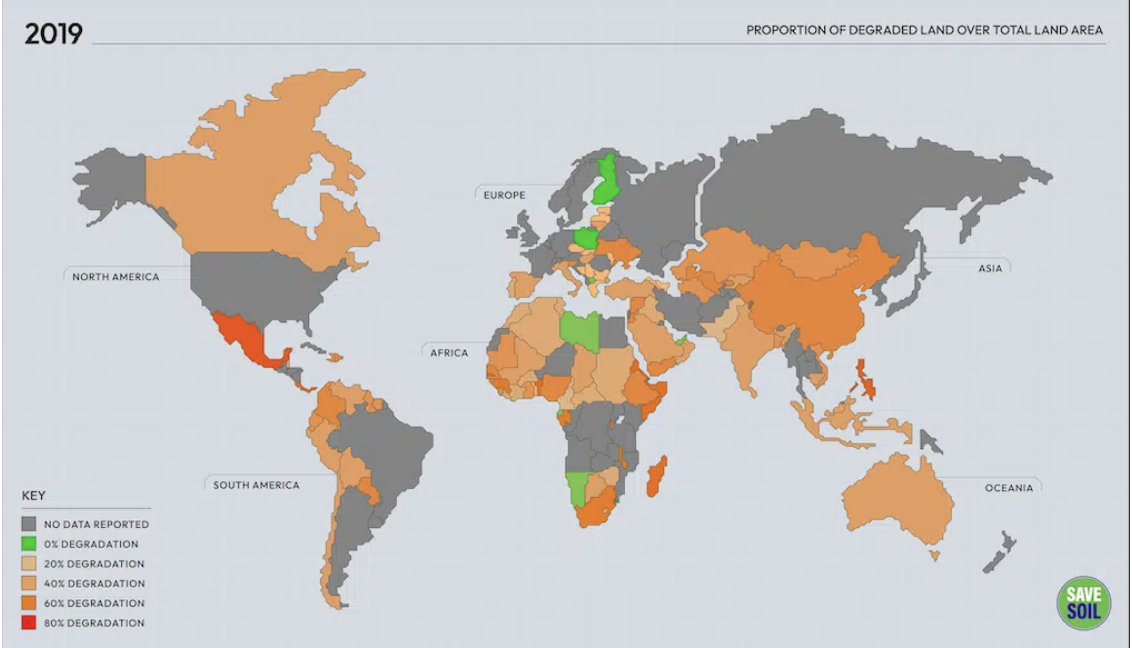

Currently, about 40% of the world’s farming soils are degraded. At present rates, the UN GEF forecasts, that by 2050 man-made degradation will affect 95%. (Fig 1). Magnifying the crisis, human numbers will reach 9.8 billion, demanding a third more food. Together these forces will place intolerable strains on industrial food production, driving it headlong to collapse in many regions.

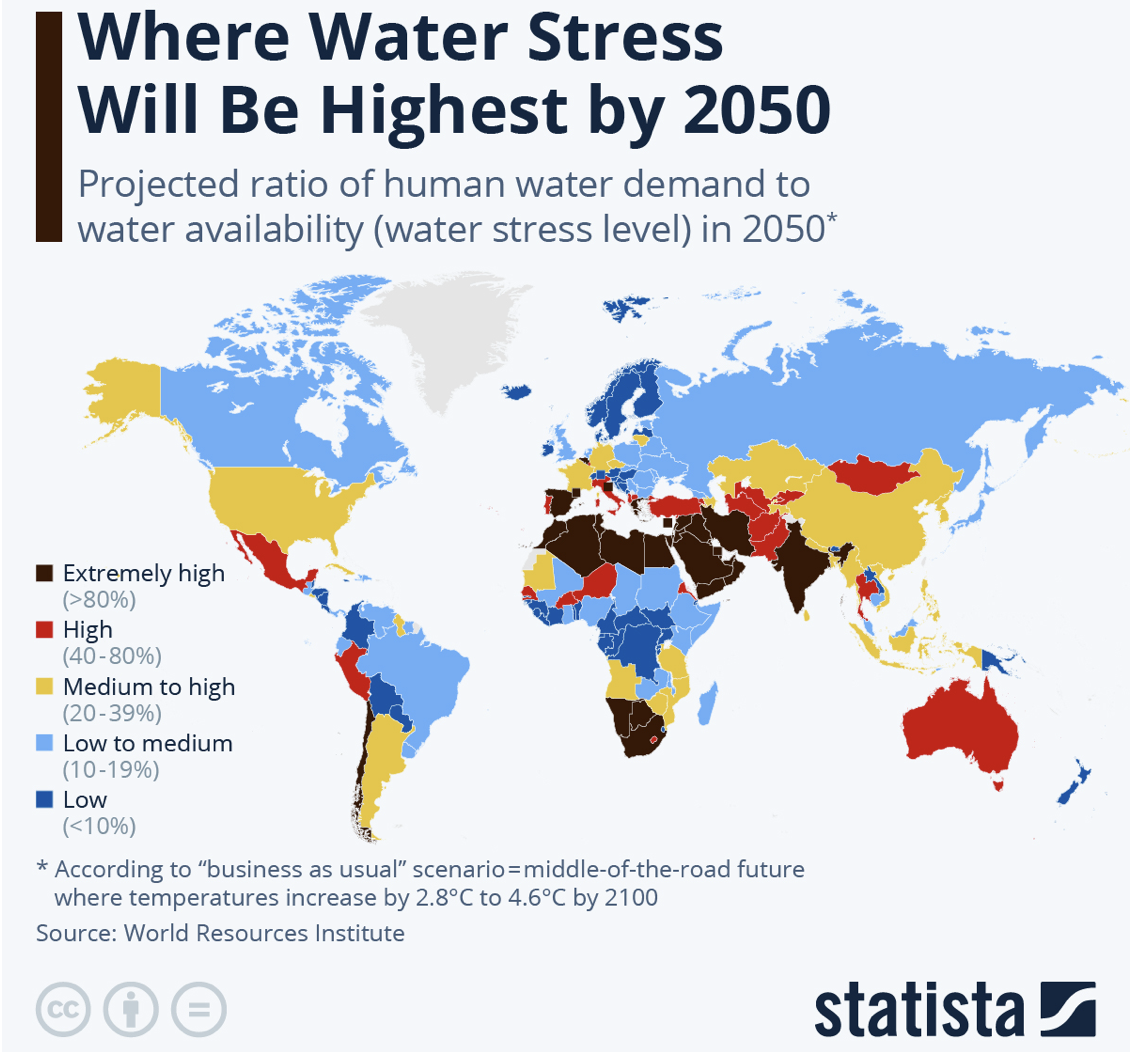

Water: The world is running out of fresh water to grow food and sustain our cities. Seventy percent of the world’s available water is now used to grow food. On average, irrigation produces about 40% of the world’s total food supply. However, with the dramatic growth in the megacities’ demand, fresh water supply has reached critical levels around the globe.

Acute water stress now affects half the planet’s population, growing more dire with the each passing year. Many major cities — such as New Delhi, Sao Paulo, Cape Town, Bangalore, Beijing, Cairo Tokyo, Mexico City and Jakarta — face grave water shortages. However, cities can afford to pay more for their water than farmers, so the market ensures water scarcity quickly becomes food scarcity.

Growing food is the most water-intensive thing we do: it takes 50-100 litres to supply the average person’s daily drinking, washing and cooking needs. And it takes 2000-5000 litres of water a day to grow our daily three meals. World water scarcity is thus likely to drive hunger, even more than in thirst.

Half of all the water used on farms comes from groundwater, which is declining in every country on Earth where it is used to grow food. This presages future shocks to both food and water supplies.

Farming ecology: The “cradle of life” that supports farming in every country is in serious trouble as a result of aggressive land-clearing, mechanisation, overuse of toxic chemicals and fertilisers, loss of pollinators and pest-eaters, soil structural decline and other factors. This is recognised by many farmers worldwide, who are desperately trying to develop a “ regenerative agriculture” that safeguards its own environment while producing clean, nutritious food. However the world’s main science effort has been enchained by giant chemical corporations, far more concerned with profit than food. Consequently, “regen farmers” and organic growers receive little support from academia or science in developing a sustainable food system – and the giant industrial food machine lumbers on the road to self-abolition.

Fragile food chains: All the world’s cities have one thing in common: not one of them can feed itself. All are supported by tenuous industrial food chains that typically extend for 2000-3000 km across nations, continents and oceans. These chains are easily shattered by floods, wars, pandemics, oil crises and politics, emptying supermarket shelves within 24-28 hours. Under the modern food supply system, a megacity can starve in under a week. Anyone who lived through COVID may recall times when supplies of various foods failed.

Combined threats: Food also provides a chilling instance of the synergy between the massive threats created by humans to our own future. Not only does climate change threaten food production directly but it also amplifies the loss of topsoil, scarcity of fresh water and collapse of agroecology, multiplying all these threats. And the conversion of farm land to desert that results, releases more carbon from the soil, accelerating climate change.

It can clearly be seen that these threats to world food security are interlinked, and cannot be separated or tackled one at a time. Together they threaten to bring down a system of food production that has sustained humanity for 10,000 years but can plainly no longer do so.

So what is the answer, you may ask?

Renewable food

The solution to the looming world food crisis is the same as for the energy crisis. Renewable food is the analog to renewable energy – with the salient different that it will create far more jobs, opportunities, new enterprises, new wealth and new industries.

In brief, renewable food will feed everyone on the planet, healthily and reliably, by recycling the water and nutrients now used to produce food by agricultural or aquacultural means. At present these are mostly thrown away in the most colossal act of waste in human history.

There are three main pillars to a renewable world food supply:

- Regenerative farming, now being pioneered by innovative farmers worldwide, which aims to prevent the damage caused to the food system by industrial agriculture and improve the health and freshness of food.

- Urban food, produced by recycling the water and nutrients currently discarded in urban waste, sewage and drainage systems, using technologies such as hydroponics, aquaponics (fish and vegetables), aeroponics, cell culture, food printers, entomoculture etc. These urban methods can reduce by up to 90% the amount of land and fresh water required to feed our cities, while providing them with a fresh, healthy and non-toxic food supply sufficient for all, in all countries.

- Deep ocean aquaculture of marine plants and animals, grazing and carnivorous fishes on large rafts located in the deep oceans where currents remove all waste and nutrients are pumped up from the deep ocean to irrigate seaweeds (algae) at the base of the food chain. Unlike coastal fish farms, deep ocean farms do not pollute or destroy wild ecosystems such as mangroves and seagrass beds. This is a relatively new technology and requires rapid development.

Each of these pillars is potentially capable of supplying a third of the world’s food needs on a renewable basis – unlike the present corporatised food chain, which devours itself. By locating them in or close to big cities and in all countries, they can enable every nation to grow adequate food for its own citizens without depending on imports from food-rich countries. This will end hunger and, to a large degree, help to end poverty.

Renewable food has two other major benefits that nobody talks about: it can prevent most wars and it can also end the 6th extinction of life on Earth.

Over the past century, two-thirds of all wars, civil and international, have been fought over food, land and water. It follows that eliminating food insecurity is the best way to reduce the tensions that fuel conflict, making food the most powerful “weapon of peace” on the planet.

Second, replacing industrial agriculture with renewable food, will free up almost half of the planet for rewilding and this, in turn, will help to end the 6th extinction. This can be achieved through a globally-funded Stewards of the Earth scheme, diverting part of the world’s present US$2.1 trillion military spending into restoring forests, grasslands and wetlands employing indigenous people and former farmers.

Renewable food thus offers practical solutions to a wide range of threats to the human future – including food insecurity, global heating, eco-collapse, global poisoning, conflict, hunger, refugeeism and poverty.

It is high time the world began to take it seriously.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.