Did the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945 end the war?

August 3, 2025

The widely accepted moral justification for the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was that they brought a quick end to the war which if continued would result in more widespread deaths and destruction.

An edited and updated repost from 27 May 2016

There is an argument that what the Japanese military feared most of all was not the bombing of civilians, but the threat of Soviet occupation and perhaps partition of Japan.

Murray Sayle, in The New Yorker in 1995, argued the importance of the Japanese military and its fear of the Soviet military that was decisive in ending the war.

Sayle was a widely admired Australian journalist. When the London Times refused to publish his report on the Bloody Sunday shootings in Northern Ireland in 1972, he left the paper and moved to Japan. His Bloody Sunday article proved to be accurate

From Japan in 1995, he wrote the following ‘Did the bomb end the war?”

Which was the crisis that Hirohito and his divided Cabinet believed now made the Emperor’s personal decision necessary – the atomic bombs, Soviet intervention, or the worsening situation as a whole? Certainly, the new bombs added to Japan’s woes – along with the ongoing sea blockade, “conventional” firebombing, burned-out cities, total enemy control of sea and air, the shelling of ports by battleships close in-shore, mass hunger, and the promise of a meagre rice harvest. A small provincial city had been largely destroyed, by fire, and another partly destroyed. But then so had Japan’s capital, Tokyo, and the B-29s, still eliminating such “productive enterprises” as Japan “had above ground,” were doing so at least as effectively as atomic bombs could. The war had continued despite the fire raids; the new atomic weapon did not interfere with the Army chiefs’ military plans or change their indifference to civilian casualties. The Soviet intervention, however, demanded a new consensus, because it made the existing consensus inoperative. And — a point implicit in much of the leadership’s discussion — the bombs promised only to kill more Japanese, whereas the Soviets, possibly allied with local Communists, threatened to destroy the monarchy, which almost all Japanese, and certainly those in the government, viewed as the soul of the nation. A surrender with some guarantee for the Emperor thus became the best of a gloomy range of options, and the quicker the better, because every day that passed meant more gains on the ground for the Soviets, and thus a likely bigger share of the inevitable occupation. Recognition that a surrender today will be more favourable than one tomorrow is the classic reason that wars end.

In the World Post on 24 May 2016, Gar Alperovitz wrote about this same issue. In this article, Alperovitz said ‘The vast destruction wreaked by the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the loss of 135,000 people made little impact on the Japanese military."

Some extracts from Alperovitz follow:

A good place to start is with an unusual and little-noticed display at The National Museum of the United States Navy in Washington. A plaque explaining an exhibit devoted to the atomic bombings declares: “The vast destruction wreaked by the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the loss of 135,000 people made little impact on the Japanese military. However, the Soviet invasion of Manchuria on 9 August – fulfilling a promise made at the Yalta Conference in February – changed their minds.”

Though the surprising statement runs contrary to the accepted claim that the atomic bombs ended World War II, it is faithful to the historical record of how and why Japan surrendered. The Japanese cabinet — and especially the Japanese army leaders — were not, in fact, jolted into surrender by the bombings. Japan had been willing to sacrifice city after city to American conventional bombing in the months leading up to Hiroshima – most dramatically in the 9 March firebombing of Tokyo, an attack that cost an estimated 100,000 lives.

What Japan’s military leaders were focused on was the Red Army, which was poised to take on the best of Japan’s remaining army in Manchuria. The historical record also makes clear that American leaders fully understood this. Indeed, before the atomic bomb was successfully tested, US leaders desperately sought assurances that the Red Army would attack Japan after Germany was defeated. The president was strongly advised that when this happened, Japan was likely to surrender with the sole proviso that Japan be allowed to keep its emperor in some figurehead role.

The unusual pattern of events — with the combined U.S. military leadership strongly urging a course of action deemed likely to save lives, and the president resisting — has, of course, raised questions in the minds of many as to whether other issues were involved.

The most obvious alternative explanation was put forward by early post-war critics who pointed out that there is considerable evidence that diplomatic reasons concerning the Soviet Union — not military reasons concerning Japan — may have been important. For instance, after a group of nuclear scientists met Truman’s chief adviser on the atomic bomb, US Secretary of State James Byrnes, one reported that, “Mr Byrnes did not argue that it was necessary to use the bomb against the cities of Japan in order to win the war … Mr Byrnes’ … view [was] that our possessing and demonstrating the bomb would make Russia more manageable”.

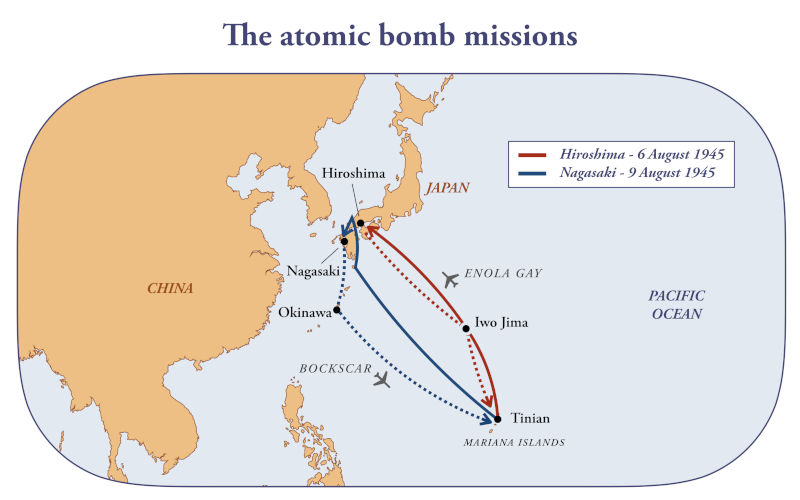

Close attention to some key dates is also instructive. The Soviet Union was expected to enter the Japanese war three months after Germany surrendered on 8 May – which would have put the Red Army attack on or around 8 August. Hiroshima was destroyed on 6 August and Nagasaki on 9 August.

The Navy Museum plaque is not the only evidence that some of the nation’s most important military leaders had grave misgivings about using the atomic bombs against the largely civilian targets of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. For instance, the president’s chief of staff — William Leahy, a five-star admiral who presided over meetings of the Joint Chiefs of Staff — declared in his 1950 memoir:

It is my opinion that the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender … My own feeling was that in being the first to use it, we had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages. I was not taught to make war in that fashion, and wars cannot be won by destroying women and children.

Similarly, the five-star general who oversaw America’s military victory in World War II and later became president, Dwight Eisenhower, declared publicly in 1963 that, “it wasn’t necessary to hit them with that awful thing”. In his memoirs Eisenhower recalled that when he was informed by Stimson that the atomic bomb was about to be used:

I voiced to him my grave misgivings, first on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and second because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives.

A few weeks after the bombing, US Major General Curtis LeMay, the famous “hawk” who led the 21st Bomber Command, an air force unit that was involved in many bombing operations against Japan, stated publicly:

“The war would have been over in two weeks without the Russians entering and without the atomic bomb … [T]he atomic bomb had nothing to do with the end of the war at all.”

And a 29 May 1945 memorandum written by US Assistant Secretary of War John McCloy shows that America’s top military leader, US General George Marshall,

thought these weapons might first be used against straight military objectives such as a large naval installation and then if no complete result was derived from the effect of that, he thought we ought to designate a number of large manufacturing areas from which the people would be warned to leave – telling the Japanese that we intend to destroy such centres.

What really happened in the days leading up to the decision to destroy Hiroshima and Nagasaki may never be known. Enough is known, however, to underscore a critical lesson for the future: Human beings in general, and political leaders in particular, are all too commonly prone to making decisions that put near-term political concerns above truly fundamental humanitarian concerns.

Alperovitz is the author of two major studies of the atomic bombings: “ _Atomic Diplomacy: Hiroshima and Potsdam_” and “ The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb,” where references to the key documentary sources in this piece can also be found.