Environment: 18th century vicar describes controlled burning in English countryside

August 17, 2025

English farmers used controlled burns of gorse 300 years ago. Too hot and dry even for cacti. Urbanisation induces genetic evolution in birds. China powering ahead with the roll out of wind and solar.

Controlled burning in 18th century England

Being slow on the uptake, non-Indigenous Australians have only recently recognised the importance of the traditional, deliberate use of fire by Aboriginal groups (cultural, controlled or cool burning) to improve environmental health, promote biodiversity and reduce the risk of late season, very hot, destructive fires triggered by lightning.

Even less well known is that controlled burning was also practised in England in the 18th century, as illustrated by this quotation from a letter written by the Reverend Gilbert White to the naturalist Thomas Pennant around 1770:

“ … in this forest, about March or April, according to the dryness of the season, such vast heath-fires are lighted up, that they often get to a masterless head, and, catching the hedges, have sometimes been communicated to the underwoods, woods and coppices, where great damage has ensued. The plea for these burnings is, that, when the old coat of heath, etc. is consumed, young will sprout up, and afford much tender brouze [shoots] for cattle; but, where there is large old furze [gorse], the fire, following the roots, consumes the very ground; so that for hundreds of acres nothing is to be seen but smother and desolation, the whole circuit round looking like the cinders of a volcano; and, the soil being quite exhausted, no traces of vegetation are to be found for years.”

White was an avid, keen-eyed, knowledgeable and meticulous observer and recorder of the geology, soils, flora, fauna and farming practices of his parish in southern England. He maintained a regular correspondence with fellow naturalists in which he described his observations in considerable detail. Well ahead of his time, he was a painstaking observer of behaviours (for instance of small animals such as harvest mice, swallows and his pet tortoise), of change (for instance of times of flowering) and of the relationships between, and interdependence of, species. His writings are considered a foundation of the Arcadian school of ecology that advocates a harmonious relationship between humans and nature. White met Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander and his observations influenced Charles Darwin.

Thirty-five of White’s letters to Pennant and nine to Daines Barrington were collected into a book, The Natural History of Selbourne, that was first published in 1789 and has been continuously in print ever since. One can’t help suspecting that the pastoral care associated with White’s parish was not overly taxing.

If you ever find yourselves near the Hampshire-Sussex border, I can recommend a visit to Gilbert White’s House and Garden in Selbourne, about 25km east of Winchester.

Cacti suffering in the heat

In Australia we have become very aware in the last decade of the risks of climate change to our coral reefs, especially of the causal chain from global warming to warmer oceans to marine heatwaves to coral bleaching to coral death. The Great Barrier Reef has suffered five severe heat-induced coral bleaching events in the last 10 years compared with only two previously (in 1998 and 2002) and this year the relatively unscathed reefs off Western Australia are suffering from high water temperatures.

But cacti are used to living in high temperatures; surely they are secure from the risks of global warming? Apparently not.

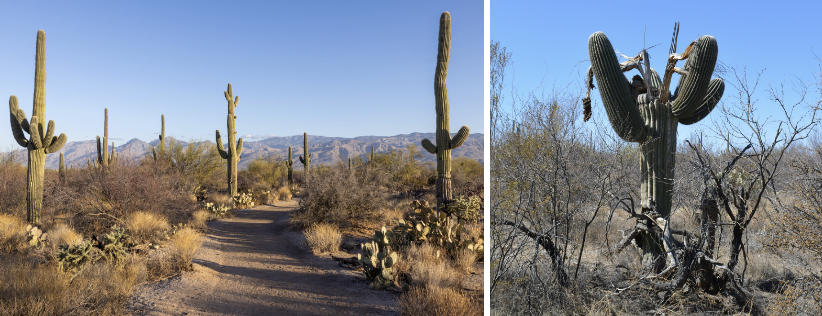

In the Sonoran Desert, around the junction of Mexico, California and Arizona, the tall columnar cacti that are so iconic of the area (and Westerns) are suffering from “cactus scorching”. This has been caused by exposure of the cacti to the increasingly common, extremely high temperatures and severe droughts in the area.

During periods of extreme heat or drought the tissues responsible for photosynthesis in the outer cells of the cactus become rapidly discoloured and the “skin” of the cactus turns brown. The cells’ capacity to photosynthesise is lost, the cells’ whole metabolism fails, the cells die and, if the damage is severe enough, the cactus dies. Tissue scorching is associated with a three-fold increase in the mortality of giant cacti and even among those that survive there is long-term decline in health.

Healthy and dying saguaro cacti in southwestern US

Cactus scorching caused by climate change is not the only problem cacti face at present. Invasive grasses, fires, severe winds, habitat loss and opportunistic insect attacks threaten whole populations of keystone species of columnar cacti and the ecological communities that depend on them. The climate change-related threats to cacti are global, not simply in southwestern US.

How well do you know your …

Of which group of fundamentally important living organisms is “arbuscular”, the oldest and commonest of four main types? “Ericoid” and “orchid-specific” are two of the other types.

The arbuscular type is so common that it is associated with 70% of global plant biomass and yet its members do not exhibit the characteristic that we most commonly associate with this form of life. In fact, the word “arbuscular” may, possibly inadvertently, give you a clue to the answer.

Hint : a member of the fourth type has featured prominently in the news recently.

Human-induced evolution in birds

If you think that “character displacement” refers to Donald Trump pretending to be or, if you believe in miracles, actually becoming a nice guy, sorry, you’re wrong.

_“_ _Character displacement_ is an evolutionary process in which natural selection acts to alter some aspect of an animal’s behaviour or physical structure to reduce costly competition from other, usually similar, species. An often-cited example of character displacement occurs in Darwin’s finches, a group of closely related songbirds in the Galapagos Islands that evolved bills of differing shapes and sizes to specialise on different food sources. An example of character displacement involving vocalisation comes from the amphibian world: female New Mexican spadefoot toads usually prefer males with faster calls, but in areas where the New Mexican species shares space with the Plains spadefoot toad (which has a similar call), those females have evolved a preference for slower calls by males to avoid mating with the wrong species.”

In Boulder, Colorado, the expansion of the urban area, planting of deciduous fruit trees and maples and the increasing presence of bird feeders in gardens is creating an area of habitat overlap of two closely related species of chickadee. The two species look similar and have similar songs, although the Mountain Chickadees’ song contains more notes. Up to now the two species of chickadees have been geographically separated by vegetation type and altitude.

Where the two species are now cohabiting, the Mountain Chickadees are singing songs with even more notes and smaller pitch changes between the notes than the Mountains that don’t live near the Black-capped Chickadees. (The linked article has recordings and graphs of the songs.)

The researchers postulate that the Mountains are changing their tune in the areas of overlap to avoid conflict (for instance, over mates, which leads to hybridisation or nesting sites or food) with the more dominant Black-cappeds. If, in the areas of overlap, the Mountains with the changed tune have a survival advantage over those that keep the old tune, the genome of the Mountains in the area will change and the species will evolve. Perhaps into a new species that can no longer breed with the Mountain Chickadees that still live apart from the Black-cappeds.

The influence of humans on the evolution of other species has similarities with the story last week about cod in the Atlantic Ocean and reinforces the message from the article on mammalian biomass a couple of weeks ago that humans are most certainly not ‘too small to matter’ in the grand sweep of nature.

Adani coal mine has paid no tax and may never pay any

After a decade of delays to negotiate objections, Adani’s massive, controversial Carmichael mine in central Queensland started exporting coal three years ago.

During Adani’s long battle to get approval to open the mine, the company, vigorously supported by the Mining Council of Australia, loudly and frequently promised that it would pay $22 billion in taxes and royalties.

Despite generating good income from the mine’s exported coal, Adani has so far paid no tax – zilch, zero. In 2025, for example, the mine earned $1.27 billion in revenue but reported a financial loss and Adani paid no tax. It’s possible that the mine will not generate a cent of tax during its planned 60 years of operation.

The fact is that the government has received more income from me personally in fines for civil disobedience ($1100 trespass, causing an obstruction and contravening a direction) at the mine construction workers’ camp in 2019 than Adani has paid in tax.

The tragedy, of course, is that Adani has probably not broken any company or tax laws. The real fault lies with Australian Governments, not Adani.

China’s utility-scale wind and solar energy explosion

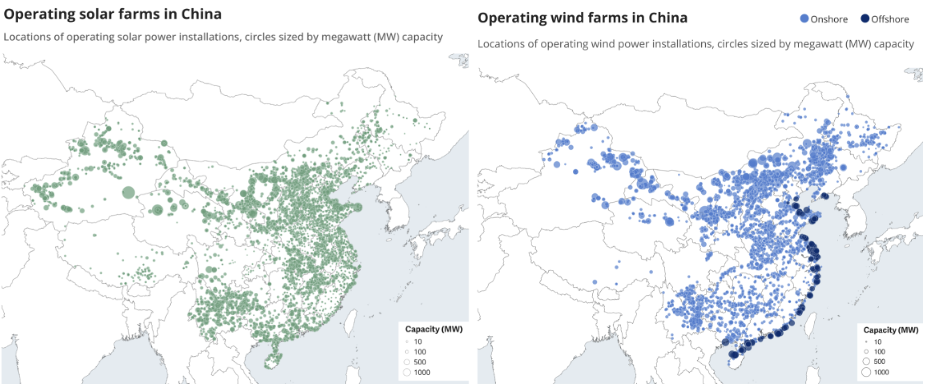

China has 1.4 terawatts (TW) of utility-scale solar and wind capacity already operating. 10% of this (140 gigawatts – GW) was added in 2014.

A further 510 GW is already under construction and 530 GW is in pre-construction phases. China accounts for three-quarters of all wind and solar projects under construction.

China’s offshore wind capacity has increased eight-fold in seven years and China now has 50% of the world’s capacity. (The US has 6% and falling.)

The maps below show China’s operating solar farms with a capacity of a least 1 MW and operating wind farms with a capacity of at least 10 MW.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.