Environment: Humanity’s big success: turning forests from saviours to spoilers

August 24, 2025

We’re destroying the ability of forests to mitigate global warming. Extreme weather events cause food price hikes and social unrest. Airlines are ignoring sustainable aviation fuel, but does it matter?

Forests are going from carbon sinks to carbon sources

By absorbing CO2 from the atmosphere for photosynthesis during the day and releasing excess CO2 into the air at night, vegetation (in forests, grasslands, mangroves, peatlands, swamps, etc.) has played a crucial role in keeping the atmospheric CO2 level just right for humans since the last Ice Age.

CO2 makes up only 0.04% of the air around us, but even at such a low concentration it has, for the last 12,000 years, kept the global temperature at an average of about 15oC, which has allowed humans to thrive over most of the world’s land surface. To use the now well-worn metaphor, atmospheric CO2 acts like a blanket around the Earth to stop us freezing to death. Without it, most of the incoming sun’s energy would be radiated back in to space and the average global temperature would be about -21oC – much too cold for humans. But the amount needs to be just right. Too little CO2 in the atmosphere and it gets too cold for humans, too much and it gets too hot for human comfort, health and, eventually, survival. Just for comparison, the global difference between an ice age and a period between ice ages has averaged about 5oC.

Over the last 200 or so years, humans have been pumping more and more CO2 into the atmosphere, principally as a result of burning fossil fuels and releasing the carbon in them that has been buried deep underground for the last 300 million years. Thankfully, vegetation has been doing humans a great service by removing about 30% of that additional fossil fuel-generated CO2. Forests, in particular, have played a highly significant part in this removal process and are often referred to as “net carbon sinks” because they absorb more CO2 from the air during the day than they release into it at night.

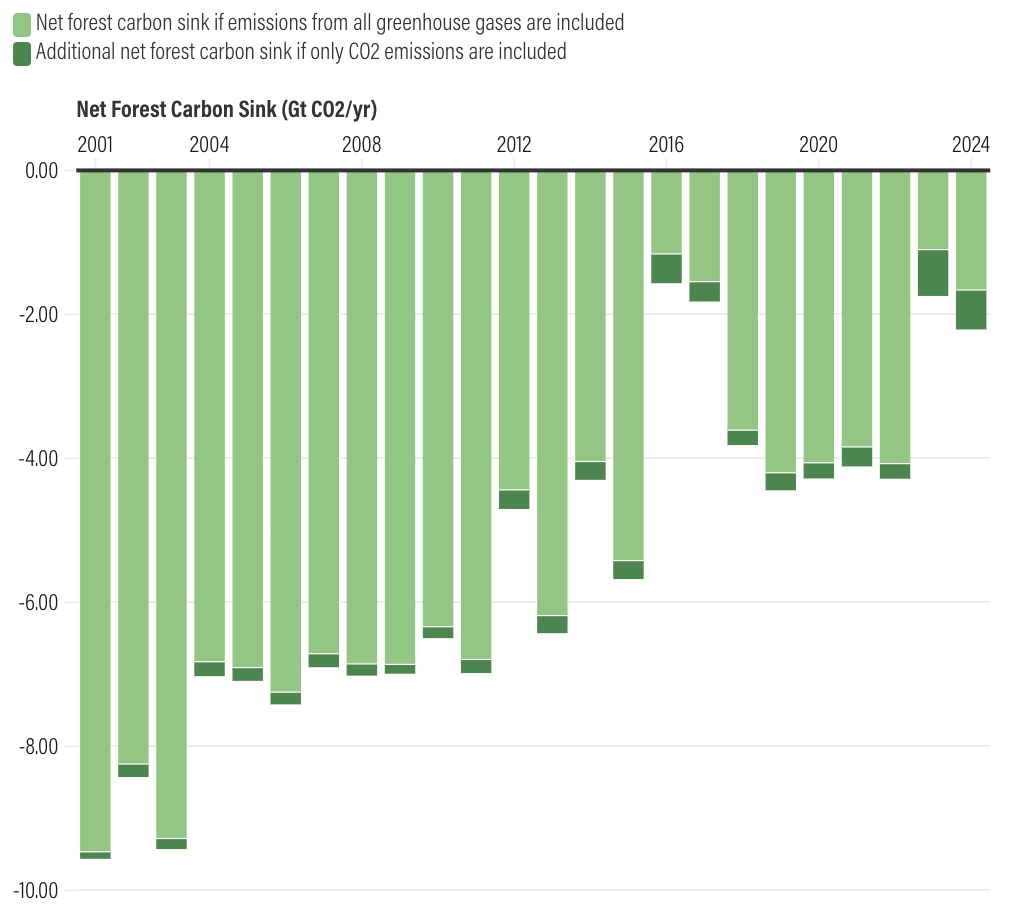

Over recent decades, however, the ability of the world’s forests to absorb CO2 has declined and CO2 emissions from them have increased. The inevitable outcome has been a reduction of the net carbon sink created by forests. The histogram below shows that 20 years ago forests had a net effect of removing around 8 Gt CO2/year, but that it has been steadily decreasing since then and in 2023 and 2024 it was about only 2 Gt CO2/year. The result has been an increase in the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere, increased and accelerated global warming, more extreme weather events, some of which are also more extreme, and increased harm to humans and damage to food and water security, infrastructure and the environment itself.

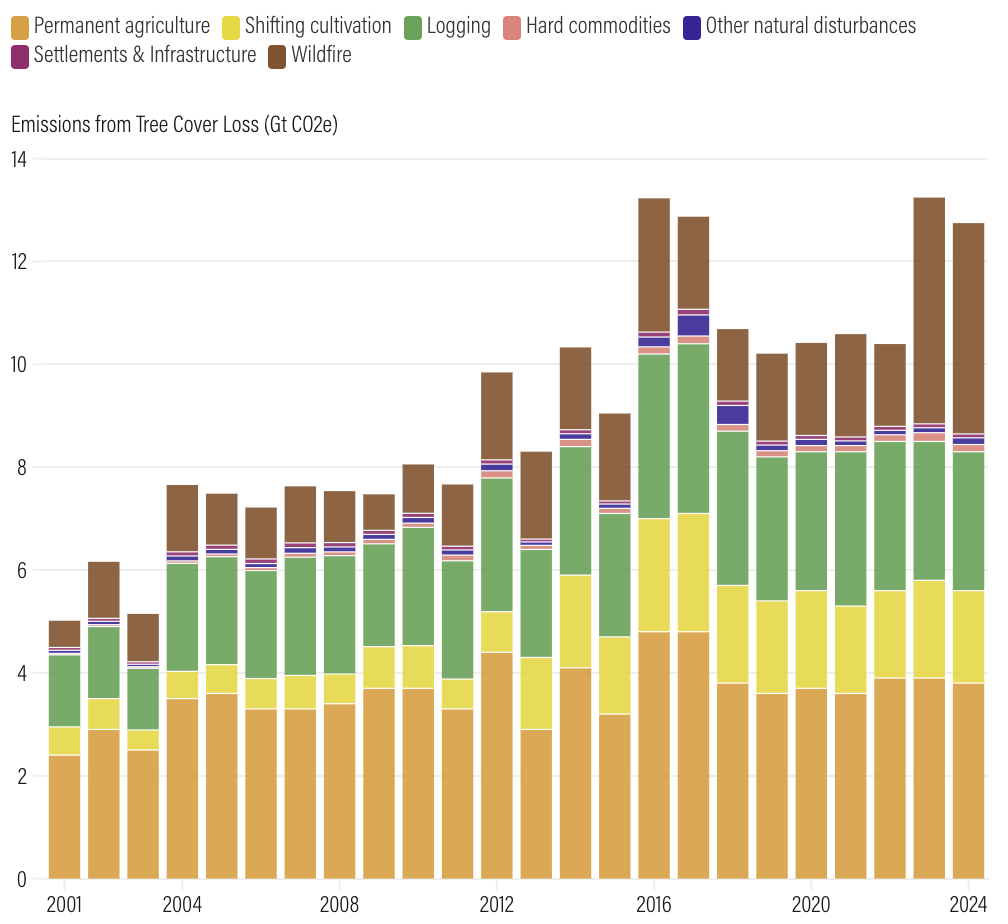

The principal cause of forests’ declining sink effect during the 21st century has been humans (see histogram below). Half the decline in the size of the sink has been due to the clearing of forests for agriculture, but logging has also been a significant problem. The area of forest cleared for mining, human settlements and infrastructure has overall been very small, but it has had devastating effects on many local ecosystems and communities, particularly Indigenous populations.

The situation changed in 2023 and 2024 when extreme fires all around the world and across many latitudes caused a 75% reduction in forests’ ability to absorb CO2 and a 2-3 fold increase in the CO2 produced by trees.

The good news is that globally forests still act as a net carbon sink, but the bad news is that the effect is weakening and some forests, such as the Bolivian Amazon and the Canadian boreal forests, are now net sources of carbon.

What do we need to do to protect the ability of forests to continue to function as a net carbon sink and protect Earth’s Goldilocks temperature? Same old, same old:

- Stop logging native forests and let naturally regenerating secondary forests stand longer. Middle-aged secondary forests and tropical and sub-tropical primary forests are particularly good at absorbing CO2;

- Reduce fire risk through prescribed burns, thinning, fire-resilient reforestation, etc.;

- Sustainably manage working forests;

- Support the Indigenous people who have over time proven themselves good at protecting forests;

- Reduce the overconsumption of food, timber, minerals etc. and align supply chains with forest protection; and one other thing … what can it be?

- … oh yes, reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

(For completeness, I’ll also mention that when the Earth warms due to more CO2 in the atmosphere, the area covered by ice diminishes and the land and water surface area grows. Ice, being highly reflective, reflects much of the sun’s energy that hits it back into space, but land and sea absorb much more of that incoming energy than ice. So, as the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere rises, not only does Earth get a thicker blanket, it also replaces a mirror with a red brick pavement.)

Extreme weather events, food prices and social upheavals

Since 2022, there have been multiple examples of extreme weather events (higher temperatures, floods, droughts, hail and cyclones, sometimes followed by opportunist pests) affecting an agricultural area and causing a rapid rise in the price of food. Sometimes several crops have been damaged and sometimes one in particular; sometimes the damage has been mainly local, sometimes global, sometimes temporary and sometimes long-term. For instance:

- Heat waves in East Asia in 2024 caused increases in the price of Korean cabbage by 70% and Japanese rice by 50%;

- Droughts in California and Arizona in 2022 contributed to an 80% rise in US vegetable prices, and in Southern Europe in 2022/23 droughts caused a 50% rise in the price of Spanish olive oil, which constitutes 40% of world supply;

- Following a drought in 2023, heat waves in February 2024 in Ghana and the Ivory Coast, which together supply nearly 60% of the world’s cocoa, caused cocoa prices to increase globally by 300% by April;

- And who could forget that floods in Queensland in 2022 caused the price of lettuce to rise by 300%?

Climate-driven food price spikes can have serious social consequences such as increased food insecurity, particularly in low-income families; less healthy food choices exacerbating health problems such as heart disease, diabetes and cancer, with flow-on consequences for people’s mental health and the health system; and increased inflation leading to higher interest rates that put further pressure on already stressed household budgets. All of these can have electoral consequences and there is evidence of food price inflation contributing to social upheaval and revolutions, for instance in France in 1789, Russia in 1917 and North Africa in 2011 (the ‘Arab Spring’).

The obvious sensible response to these climate-driven food price surges is to rapidly reduce greenhouse gas emissions to lower the risk of global warming and extreme weather events. As there is little hope of that happening in the foreseeable future, action is needed to better prepare societies to respond to the increasingly likely failures of essential crop. For instance:

- Timely information about the next year’s weather and the possible effects on crops and prices allows producers to change crops and/or planting schedules;

- Better understanding of climate change, combined with government incentives, could help farmers make long-term changes to crop selections and agricultural methods;

- Depending on local circumstances, implementation or abandonment of irrigation schemes;

- Social security programs that strengthen the capacity of vulnerable groups to prepare for, and respond to, climate-driven food price shocks; and

- Multidisciplinary research and planning to identify the complex local and global interactions of the environment, farming, food and transport systems, trade, socio-economic factors, prices and political systems.

Sustainable aviation fuel fails to take off

Sustainable Aviation Fuel is a kerosene-like fuel that is not produced from fossil fuels. SAF might be produced from vegetable oils, animal fats, used cooking oil, household waste, alcohol or biomass, for example. Although SAF does not come from fossil fuels, when it’s burnt in the plane’s engines it still produces about the same CO2 emissions as standard aviation fuel. SAF can currently constitute up to 50% of a plane’s fuel.

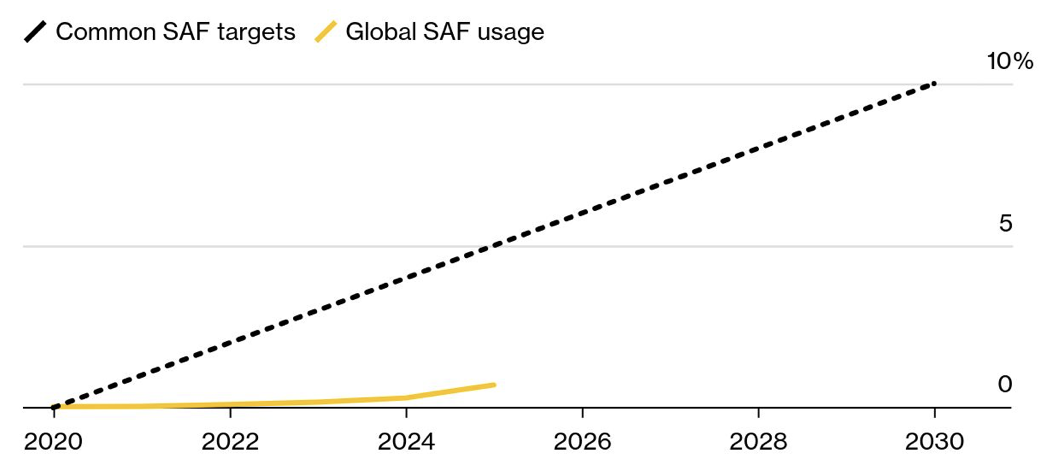

On 21 July, Bloomberg Green Daily published the graph below that compares the International Air Transport Association’s target for the use of Sustainable Aviation Fuel (as a percentage of all aviation fuels) in 2030 with the actual usage since 2020. The disparity between aspiration and achievement is disappointingly similar to that seen in many other industries.

International Airlines Group, a large European company that owns various airlines including British Airways, Aer Lingus and Iberia, led the way in 2024 with 1.9% of its fuel use provided by SAF, but even then its emissions from fuel combustion rose by 5% during the year. Generally speaking, European airlines are performing better than those from the US, although that isn’t saying much. SAF made up 0.22% of the fuel used by Qantas.

Globally, the use of SAF is expected to increase from 0.3% to 0.7% this year, but air travel is expected to increase by 6%, so emissions are going to increase again.

That all said, SAF is highly unlikely to be a either a significant or a long-term contributor to solving the aviation industry’s (admittedly hard-to-abate) emissions problem. A new generation of planes that use different sources of energy (e.g., batteries, hydrogen and hybrid) is urgently needed, but that’s a story for another day.

Overall, though, the industry does not seem to be trying very hard to make the transition.

Bye-bye coal

I imagine that this received good coverage in the mainstream media but I missed it, so just in case you did too, here’s your chance to catch up with the fun video of the simultaneous detonation of eight cooling towers in England recently.

Oh, to be in England

With no coal power there,

And whoever wakes in England

Sees, each morning, much cleaner air.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.