Environment: Humans are the wisest mammals, but which have the most biomass?

August 3, 2025

The biomass of marine mammals is almost double that of land mammals. Clean energy investments are increasing but not quickly enough. Illegal gold mining wreaks havoc on the Amazon’s Indigenous communities and environment.

Wild mammals quiz

A little quiz to start this week. Do have a punt at the answers just to see how your general impressions match the facts.

Which of the following categories of wild mammals contains the most species:

a Rabbits and hares

b Carnivores

c Rodents

Which of the following categories of wild mammals contains the most individual animals:

a Rodents

b Bats

c Hoofed mammals

Which of the following categories of wild mammals has the largest total biomass:

a Carnivores

b Hoofed mammals

c Elephants

Compared with the total biomass of all the world’s wild land and marine mammals, what is the biomass of all the world’s human beings:

a one-tenth

b one-sixth

c about the same

d 6 times more

e 10 times more

Clean energy investments are rising, but not quickly enough

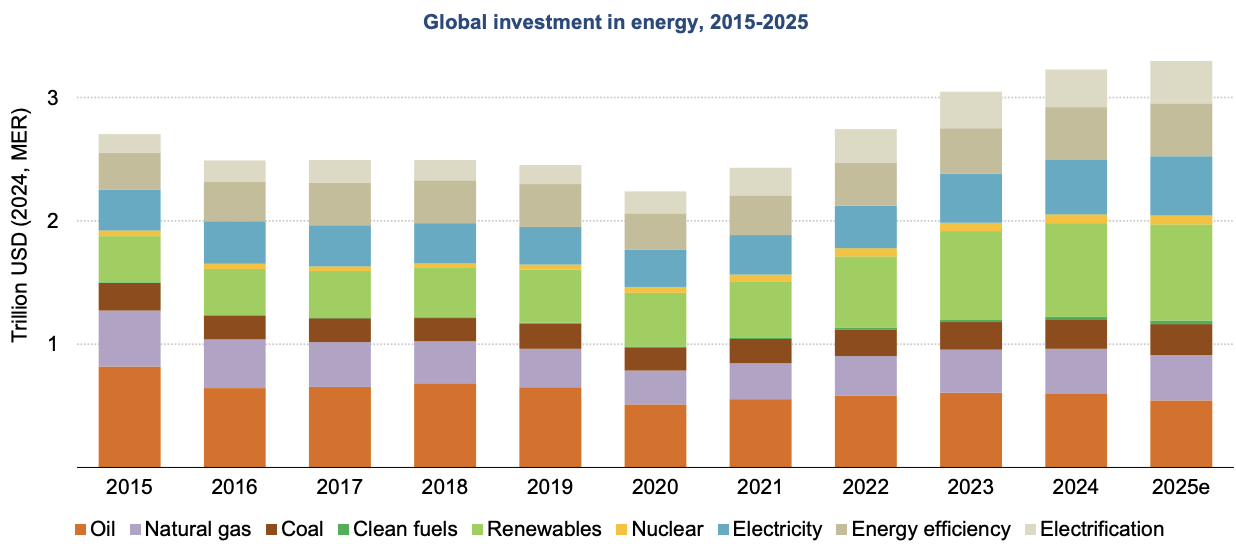

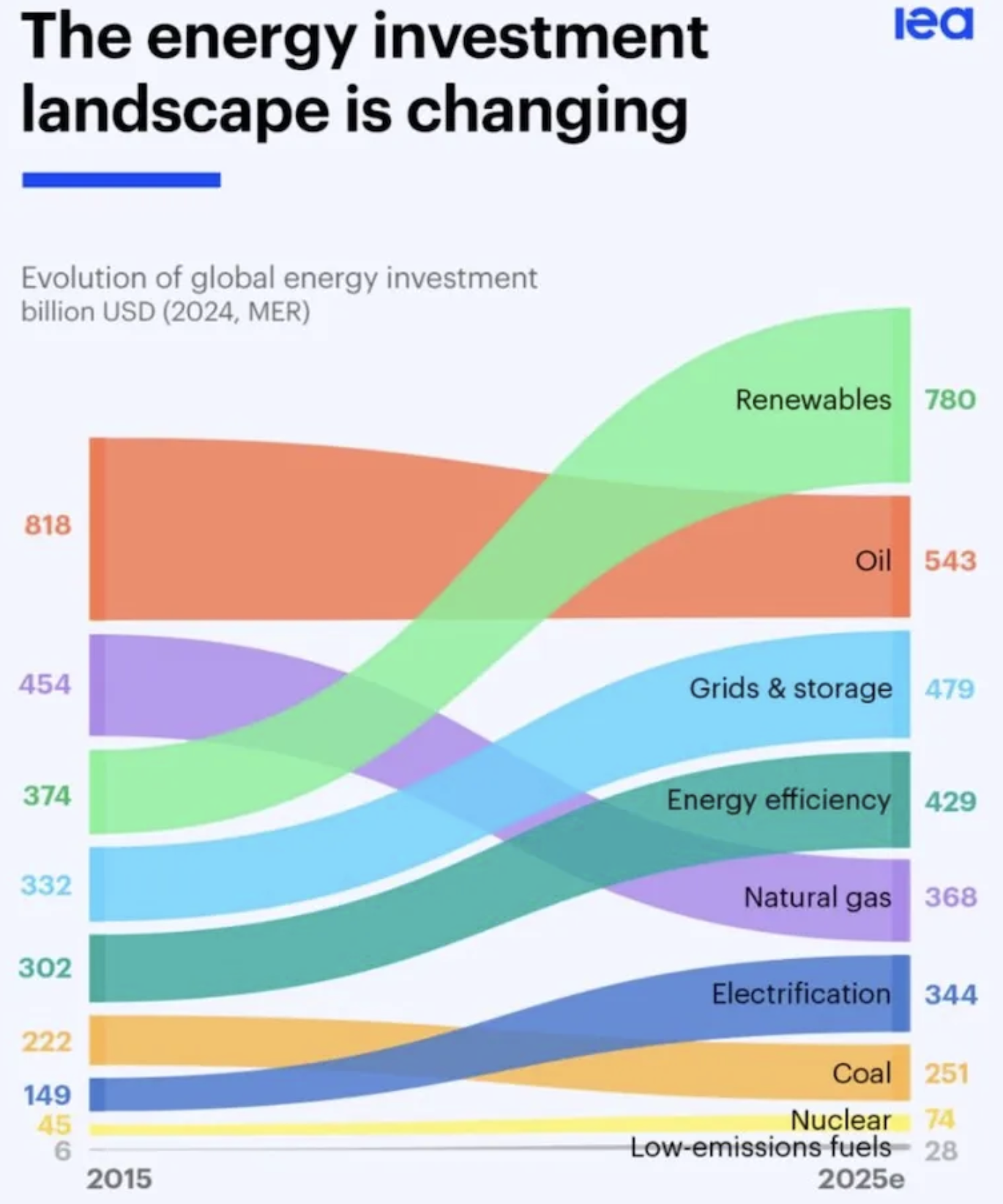

Having fallen between 2015 and 2020, global investments in the energy sector have been rising steadily since 2020 and are estimated to reach US$3.3 trillion this year, an increase of about 50% since 2020. The broad category of clean energy (which here includes nuclear) has shown the largest increase, reaching US$2.2 trillion dollars in 2025, with solar (in particular), wind, EVs and batteries experiencing rapid growth. Unfortunately, investment in distribution grids is struggling to keep pace with the rapid roll out of renewables and increasing consumer demand.

In further bad news, investments in fossil fuels have also increased over the 2020-2025 period. Liquified natural gas facilities are particularly popular at present in the US, Canada, Qatar and, as we know, Australia. More fossil fuel investment means more fossil fuels produced, more burnt and more greenhouse gases, no matter what is happening with renewable energy.

It goes without saying that the largest investments in energy are in China (almost US$900 billion in 2025), followed by the US (almost US$600 billion) and the European Union (just over US$400 billion). Investment in renewable energy in China (more than US$300 billion) exceeds by a considerable margin the total investment in any other region of the world, never mind individual countries. As ever, Africa lags behind. Despite having 20% of the world’s population, Africa accounts for only 2% of the world’s clean energy investment. In fact, energy investments in Africa have fallen by a third since 2015.

Although the annual investment in renewable energy and energy efficiency is increasing, it still needs to double to achieve a tripling of installed renewable capacity by 2030, as agreed at the COP meeting in 2023.

The changing profile of energy investments over the last decade is nicely displayed in the graphic below.

During the 10 years, investments in renewables, grids and storage, energy efficiency and electrification have increased by 75% from US$1157 billion to US$2032 billion, while investments in oil, natural gas, coal, nuclear and low-emissions fuels have decreased by 18% from US$1545 billion to US$1264 billion.

How much do the world’s wild mammals weigh?

For most of us, the answer is probably little more than an interesting fact that we might store away for a trivia quiz. For zoologists, however, it permits comparisons of species with very different body sizes and can provide an indication of the environmental impacts of wild mammals, including possible sources of new zoonotic diseases. Remarkably, there has until recently been no rigorous estimate of the biomass of all wild mammals or of particular species.

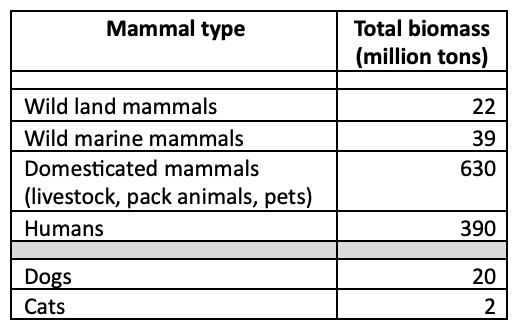

The table below provides a summary of the total biomass of major categories of wild and not-so-wild mammals:

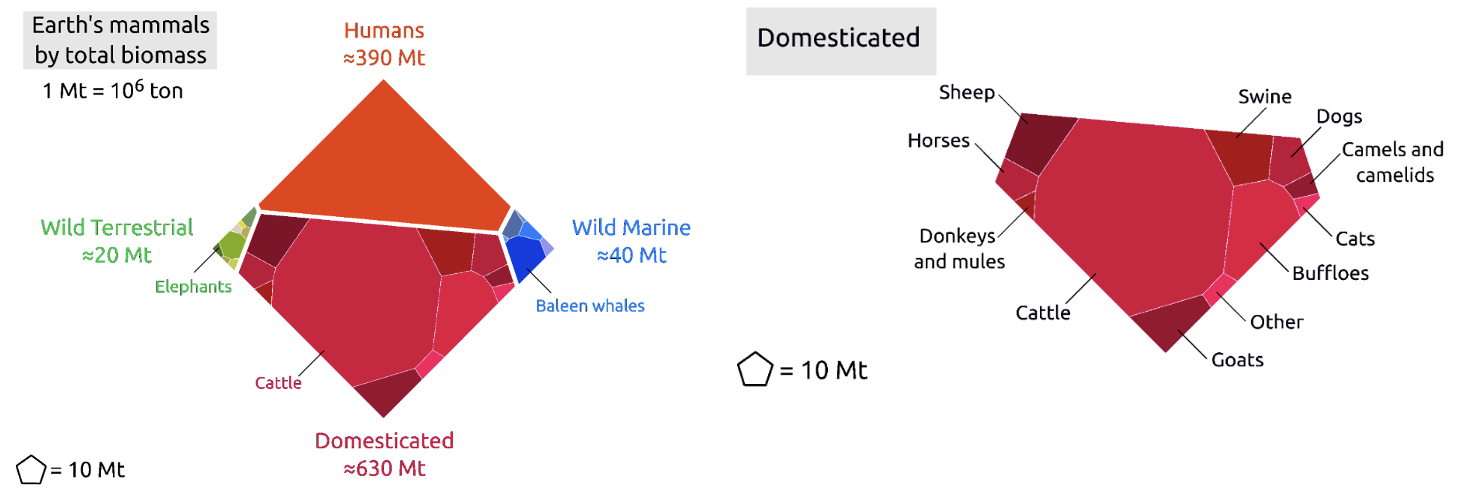

The most staggering feature of the numbers above is the enormous weight of humans and their animals, roughly a thousand million tons (Mt), compared with all the world’s wild mammals, roughly 60 Mt. Cattle alone weigh 416 Mt. Our pet dogs collectively weigh almost as much as all the wild land mammals.

The two figures below provide more details. The left one relates to all mammals and the right one to our domesticated mammals.

Focusing on the wild land mammals, just 10 species make up 40% of the total biomass; the 45 million white-tailed deer in North America alone provide more than 10% of the total. Australia’s Eastern grey and Red kangaroos come fourth and ninth in the list of species-specific biomass, together making up just under 5% of the total.

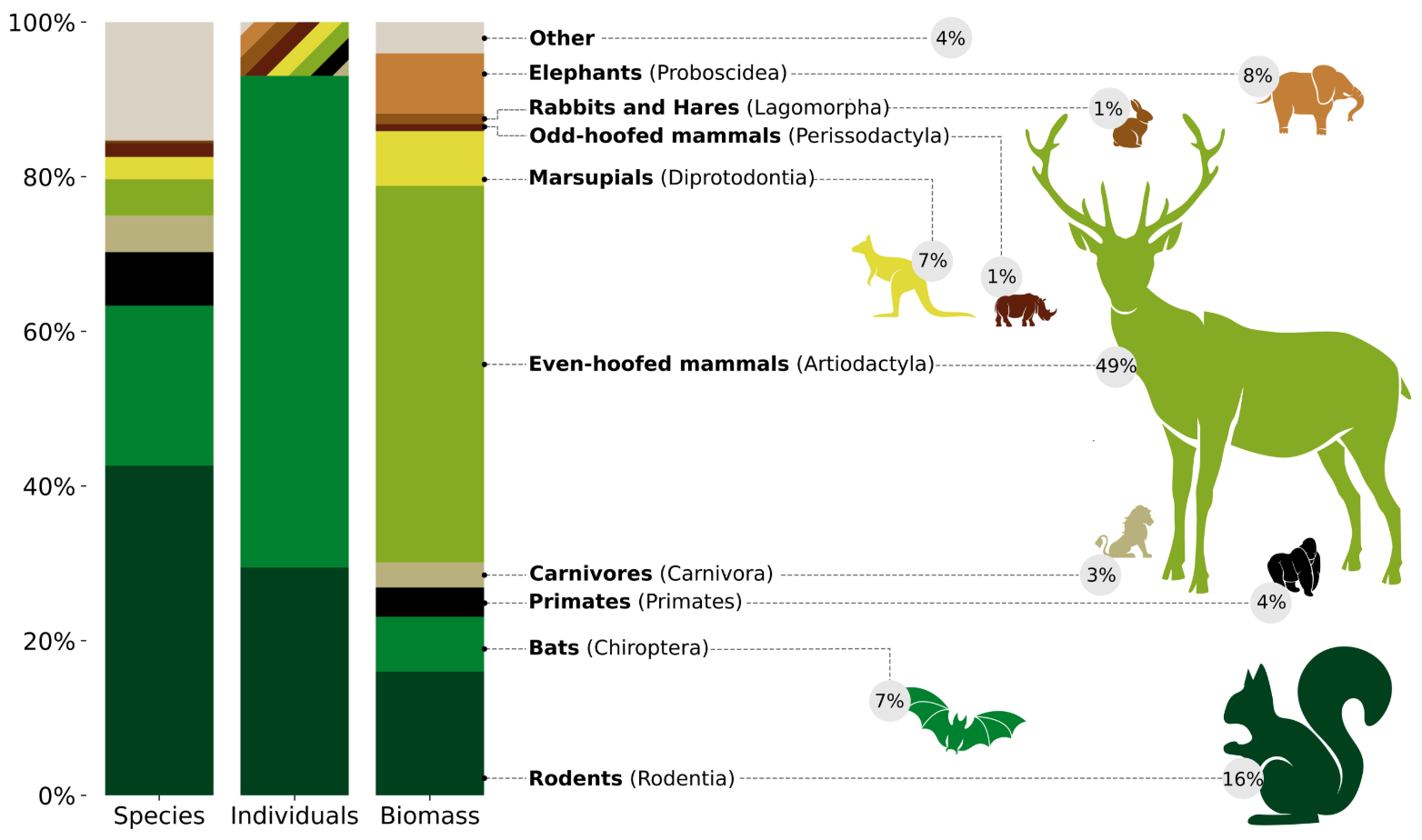

The figure below provides more details about the relative numbers of individual species and individual animals and the biomass of groups of mammals and, importantly, the answers to three of the questions above.

Most of the wild land mammal biomass is among species with body weights over 10 kg per individual. Species with body weights of under 1 kg per individual comprise more than 95% of all individual mammals, but they contribute only one-fifth of the total biomass. Bats, for example, comprise one-fifth of the species, two-thirds of the individual animals, but less than one-tenth of the total biomass of wild land mammals. The total biomass of the three elephant species is similar to that of the 1200 bat species.

In terms of the number of individuals, some species of wild land mammals (synanthropic mammals) have higher numbers when living around humans than in the actual wild. Black and brown rats, house mice and raccoons are well-known examples.

There are far fewer species of marine mammals and of individuals, but their combined biomass is almost double that of wild land mammals. The 23 Mt biomass of baleen whales (e.g., fin and humpback whales) alone is more than that of all wild land mammals. Marine mammals don’t have to support themselves on legs, of course, so they are able to sustain far heavier bodies.

The academic mammal-weighers point out that humans often hold “qualitative notions about the world that we tend to internalise, that decrease the apparent need and urgency of nature conservation efforts. Notably that the world is enormous and by corollary that natural things, shown in their explosive diversity in movies, books and museums, are seemingly endless and intuitively much more abundant than anything humanity creates”. Studies such as this provide one estimate of human impact and help to counter the unhelpful “we’re too small to matter” tendencies.

Just out of interest, my back of the envelope calculation suggests that as little as 10,000 years ago, when the human population was about five million and the domestication of animals was just starting, the human-related biomass would have been a trivial 0.25 Mt. Even 1000 years ago when the human population was, say, 400 million and animal husbandry was present, but far less intensive than today, the combined biomass would still have been less than 30 Mt (compared, remember, with the current 1000 Mt).

The 1000 Mt biomass of humans and our domesticated animals is an order of magnitude higher than that of all the wild mammals. Presumably, then, we eat an order of magnitude more food, all of which originates in photosynthesis by hard-working plants. And then there’s the order of magnitude more faeces that we produce, all of which has to be broken down by fungi and microorganisms. I wonder if all these other species realise how hard we make them work for us. I don’t think that many humans adequately appreciate their work.

Illegal gold mining in the Amazon

The approximately 1.5 million indigenous people who live in the Amazon forest have been effective conservationists. However, the Amazon’s valuable timber, wildlife and minerals make it vulnerable to illegal exploitation and many indigenous territories are not protected by either the law or government authorities.

The price of gold has increased greatly in the last 20 years (to more than $4600 an ounce this year) and globally the annual illegal flow of gold totals more than US$30 billion. No surprise then that illegal extraction of gold is now common across the Amazon Basin. The gold can be dug up following land clearing or dredged from rivers with heavy equipment. Apart from the direct damage to the forest and waterways, the mercury used to separate the gold from the ore enters the environment and poisons humans, trees, birds and fish, continuing long after the miners move on.

The revenue raised from the illegal gold is used to bankroll non-state armed groups, launder drug money, fund warfare between rival gangs of “narco gold diggers”, purchase yet more mining equipment and intimidate local communities, some of who are used as forced labour.

While responsibility for stamping out the actual mining rests with the Amazon’s various national jurisdictions, nations beyond, where the illegal gold heads, also have responsibilities to help stamp out the illegal activities.

What would you call Alaska’s most northerly reserve?

In the very north of Alaska there’s a large tract of undisturbed public land covering 95,000 km2 (half as big again as Tasmania) – see the map below. The reserve, which was created in 1923, has several Inuit communities around its perimeter. Much of the reserve is wetland and it is ecologically very significant. It supports large populations of water birds and is an important nesting area for many migratory birds. Large numbers of caribou live in the reserve, as do grizzly bears, polar bears, wolverines and wolves.

What do you think would be an appropriate name for this remote reserve with its rich indigenous culture and history, its threatened wetlands and its iconic animals? (I mock but, in fairness, the history does provide a reasonable explanation for the name, even if it seems rather incongruous in 2025, or maybe not. It is Trump’s US, sigh.)

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.