Environment: Too much and too little water causing problems from the tropics to the poles

August 31, 2025

Three-quarters of World Heritage Sites are threatened by water issues. Habitat for orangutans or electricity for the people? Summer 2024 heatwave caused massive ice melt in the Arctic. Humans, dogs, foxes, SUVs, plastics, climate change – parenting is tough for beach nesting birds.

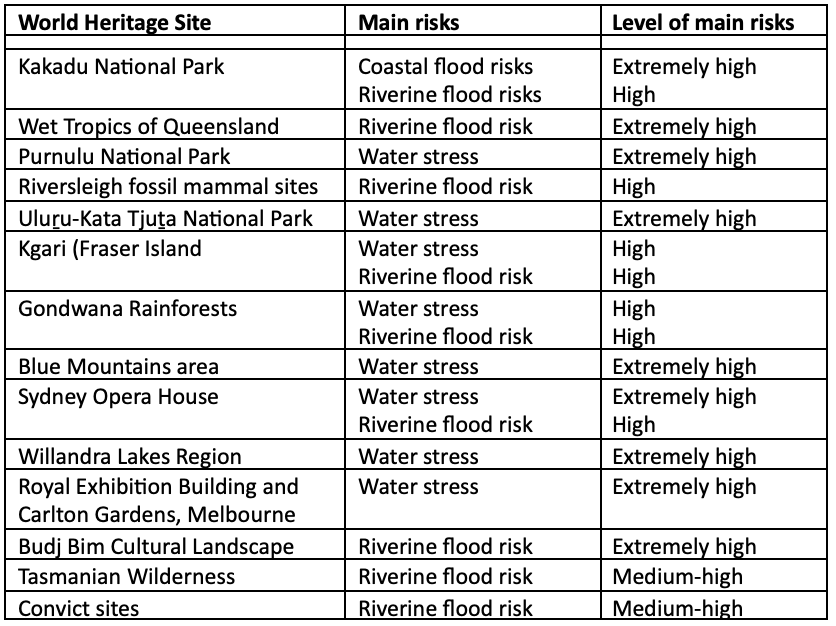

World Heritage Sites severely threatened by water problems

Globally, more than 1200 World Heritage Sites (73% of all sites) are threatened by water issues — droughts, floods, scarcity or pollution — and the number is increasing. Sites at risk include the Taj Mahal, Yellowstone and Serengeti National Parks, Petra, Machu Picchu, Mt Everest and Victoria Falls. Each red dot in the map below represents a World Heritage Site facing severe water risks. Europe is the hot spot but that’s also where the most World Heritage Sites are located.

Water stress (40% of all threatened sites) and drought (33%) are the commonest direct challenges; 21% of sites experience both drought and flooding. Climate change, with its changes to weather patterns and sea-level rise, and modern agriculture, that has raised the groundwater level in many areas and created problems with rapid water run-off during storms, are common underlying causes.

About three-quarters of the threatened sites have historical and cultural significance to humans. The other quarter are natural features where damage upsets both their structural integrity and beauty and their native flora and fauna. For instance, the drying of mud flats in the China’s Yellow Sea-Bohai Gulf region is disastrous for the 50 million migratory birds that use the area every year for rest, shelter, feeding and breeding. Too much water in the form of rising sea levels can also be problematic for wildlife in coastal areas.

Australia has its fair share of water-threatened World Heritage Sites:

Protecting the heritage of these sites for future generations depends on:

- Local actions to restore landscapes that support healthy, stable water levels, particularly nature-based solutions such as planting trees to restore headwater forests and revitalising wetlands to capture rainfall and recharge aquifers;

- National conservation policies that protect vital landscapes and prevent unsustainable developments (are you listening Minister Watt?); and

- International arrangements that value water as a common good and establish transboundary agreements on sharing water across frontiers.

Electricity for the people or a future for orangutans?

In 2017, a new great ape, a species of orangutan with fewer than 800 individuals, was officially described by a team of UK-based scientists. The orangutans live in a small, isolated patches of jungle in North Sumatra. At the time of discovery, as well as being hunted, the orangutans’ home area was already threatened by mines and palm oil plantations.

To make matters worse, the orangutans’ survival was soon made even more precarious by the construction of the Batang Toru hydroelectric dam in the middle of its range. The dam is owned by Chinese and Indonesian companies and is being financed and built by Chinese state-owned enterprises.

Scientists, environmental activists and local communities began to criticise the construction of the dam and, by 2019, were starting to have an impact, particularly after the orangutans’ discoverers published another paper that concluded that the dam might push the species to extinction. This did not please the Indonesian Government which considers the dam to be essential infrastructure (perhaps not unreasonably). The scientists were banned from working in Indonesian national parks and local opponents came under intense pressure to keep quiet (e.g., loss of jobs, threats and violence). As best I can determine, the dam is not yet operational but construction is well advanced.

What would you decide – renewable energy for people’s homes or survival of a species of orangutan, one of our closest relatives?

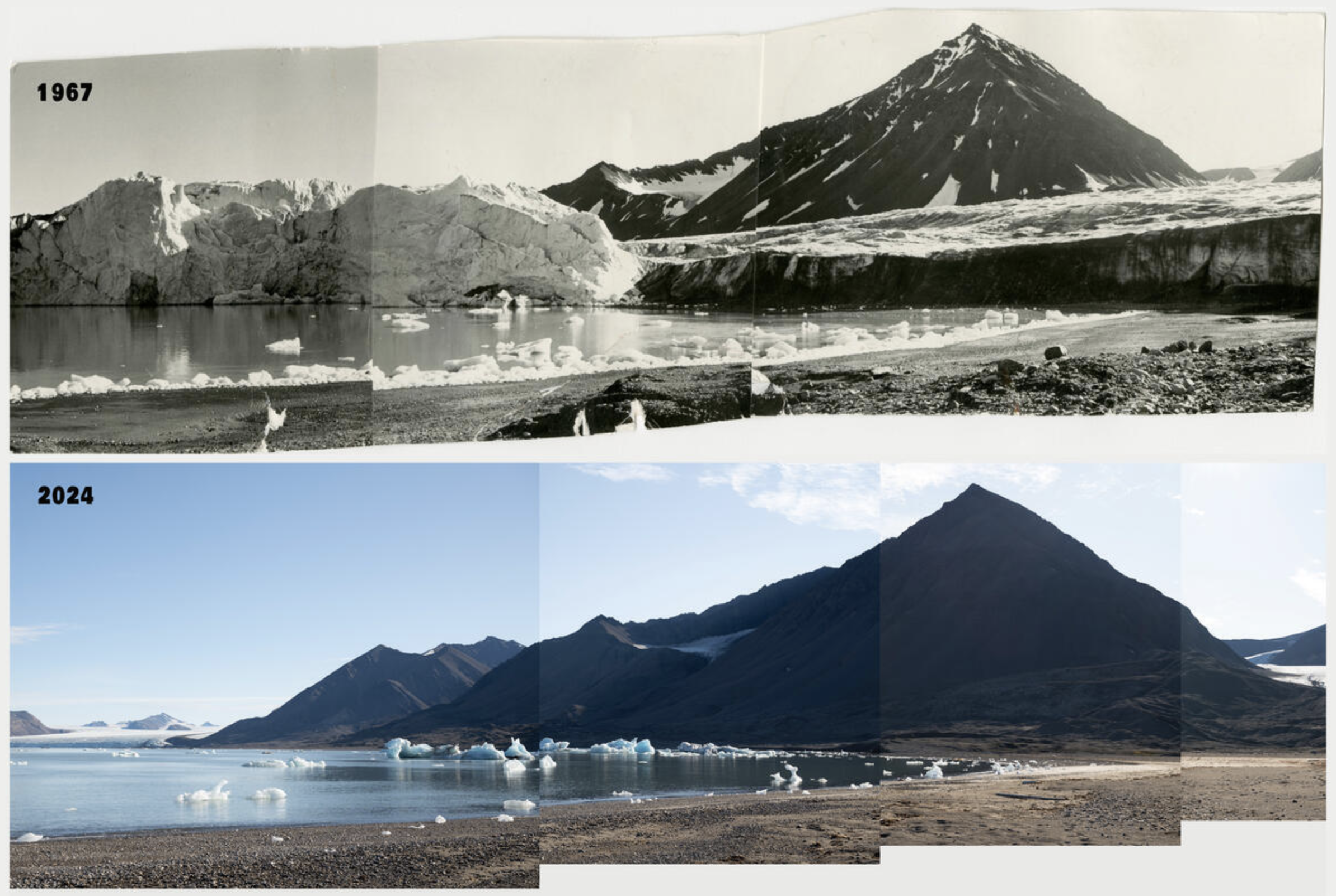

Record Arctic ice melt during 2024 summer

The Svalbard Islands are well inside the Arctic Circle, north of Norway and east of Greenland, so no surprise to learn that they are cold and icy. An Arctic heatwave during the northern summer of 2024 caused a record ice melt on the islands. About 1% of the total ice volume on and around Svalbard melted, roughly equivalent to the total ice volume of the Greenland ice sheet. So much ice melted in the adjacent Barents Sea region during just six weeks of record high temperatures that it contributed about 0.27mm to global sea leave rise, one of the most significant contributors that year.

When freshwater suddenly enters the sea, it has an impact throughout marine ecosystems from plankton, which are very sensitive to temperature and salinity, at the base of the food chain, all the way up to the fish, birds and mammals at the top. The rapid appearance of cold, fresh water in the northern North Atlantic Ocean can also cause extreme weather conditions in Europe and North America and weaken the important currents that keep water circulating around the North and South Atlantic Oceans.

According to the lead author of the study, what seems like a localised once-in-a-1000-year event will soon become normal during our lifetimes, not our grandchildren’s, and not just on Svalbard but across the whole Arctic.

The two images below show comparisons of ice sheets over longer time periods on Svalbard – Greenpeace top and Guardian bottom.

Humans and environmental change threaten beach nesting birds

At about 25cm from beak to tail (similar to a Rainbow lorikeet), Little terns are Australia’s smallest tern. They lay their eggs directly on the beach, scraping out a shallow hollow above the high-water line. The well-camouflaged speckled eggs and chicks provide good protection against predators but make them vulnerable to careless, clodhopping humans and their pets and off-road vehicles, particularly as the breeding season coincides with peak-tourism.

Little terns have recently been declared threatened in Australia as a result of:

- Disturbance and destruction of nest sites by humans, off-leash dogs, horses, boats and off-road vehicles;

- Predation by introduced and native animals including foxes, cats, dogs, goannas and birds;

- Inundation of nests by king tides, storms and rising sea levels, all exacerbated by climate change;

- Loss of habitat to coastal development and inappropriate sand management;

- Habitat degradation by invasive weeds and erosion; and

- Ingestion of plastics, entanglement in discarded fishing gear and over-fishing.

Little terns are not the only birds that nest on beaches and they all face similar dangers. Please take care when walking on beaches, you never know who might be living on the sand. If you see an area marked as an exclusion zone, it probably means that a pair of birds are actually nesting there, so please keep out.

If you have a dog, please don’t take it on beaches where dogs are not allowed. Even where dogs are permitted, please keep yours on a leash. “But there aren’t any birds around” is not a reason to let your dog run free. The sight of dogs and the smells they leave deter birds from visiting beaches – that’s why you can’t see any.

Guatemalan water hole

Do yourself a favour and watch this delightful 80-second video of animals visiting and enjoying artificial waterholes in two of Guatemala’s most important, but remote, jungle ecosystems.

Global warming in Central America is causing natural waterholes to dry up during the dry season, threatening the lives of tapirs, jaguars, deer and snakes, to name a few. Apart from capturing the visiting animals’ behaviour, the camera traps have demonstrated that animals continue to visit the waterholes during the rainy season, perhaps indicating that there are localised ongoing shortages of water or perhaps that visiting the waterholes has simply been accepted into the animals’ habits.

Some might consider this pretty low-tech initiative to be an inappropriate interference in nature, making wildlife dependent on human interventions. It seems fine to me, though, to give at least some animals a helping hand when humans are destroying their habitat and changing the climatic conditions in which they have evolved.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.