Managing a mature Australia-China relationship

August 28, 2025

The Australia–China bilateral relationship remains strong, despite Australian concerns about China’s commitment to a free and open rules-based trading system. Trump’s disruptive tariffs demonstrate that Australia must balance its relationship with the United States while ramping up cooperation on regional economic and trade issues with China.

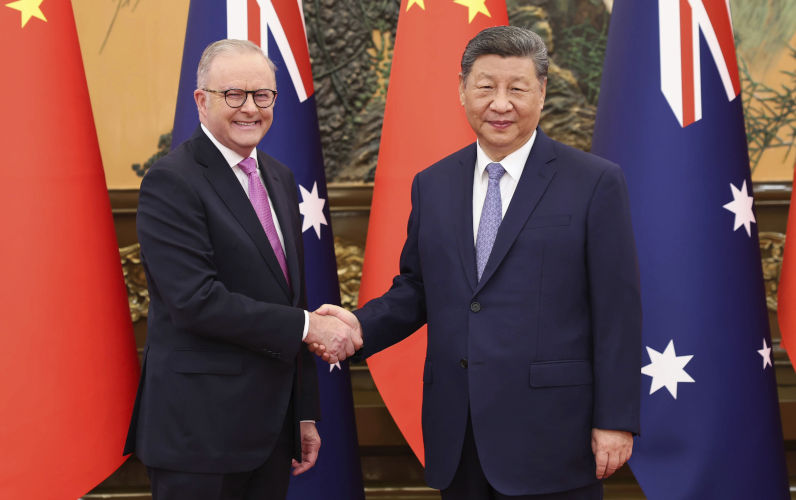

Australia–China bilateral relations, consolidated by Australian Prime Minister Albanese’s July 2025 visit to China, are as good as they have ever been. While that does not seem to bring much joy to those in the policy community and media who get their satisfaction from doom-saying and scare-mongering, it’s certainly good news, not least for the business community.

Of course there is still plenty that divides Australia and China and demands careful navigation. Australia should always listen respectfully to concerns expressed on the Chinese side, including for example whether Australia is overdoing its foreign investment restrictions, or drinking too much US Kool-Aid in defence and security policy. But Australia should never back away from making respectfully clear its own concerns on political and economic issues.

Geopolitically, Australia’s concerns include China’s territorial ambition in, and militarisation of, the South China Sea, its repeatedly stated determination to unify Taiwan with the mainland not just by persuasion but force if necessary and its dramatically increasing military capability, including nuclear arsenal. Politically, they extend to China’s intolerance of any form of real or perceived dissent, including in Xinjiang, Tibet and Hong Kong, with some of its activity extending to the attempted suppression of dissenting voices in the diaspora community in Australia.

And economically, as hugely fruitful as our relationship has been, Australia — like many other countries — still has concerns about the extent in practice of China’s commitment to a completely free and open rules-based trading system.

Concerns include the use of trade coercion for political purposes, the use of state subsidies and other support mechanisms in key industry sectors, insufficient respect for intellectual property and unjustified discrimination against foreign competitors. China was the subject of nearly half of all WTO trade complaints in 2024.

But it is important to keep all these differences in perspective. The line that is constantly repeated by Albanese and Australian Minister for Foreign Affairs Penny Wong, that we should ‘cooperate where we can, disagree where we must, and manage our differences wisely’, is not the empty cliche that some want to paint it, but a mature description of the course Australia should take.

Geopolitically, Australia must not succumb to ‘China threat’ hysteria. There is no reason to assume that, Taiwan apart, China would ever contemplate outright Putin-style military aggression against any of its regional neighbours. For Australia, physical invasion has always been wildly implausible logistically, and will remain so.

What does pose a risk is a major war erupting between the United States and China, certainly not inconceivable over Taiwan, and Australia joining under pressure from Washington. Outright invasion of Australia might not be an option, but grey-zone operations, blockade attempts and hit-and-run attacks on facilities — the increasing number of major US military installations on Australian soil being obvious targets — certainly would be. The crazy irony is that with AUKUS and its associated basing commitments Australia is spending an eye-watering amount to build a capability to meet military threats which are only likely to arise because Australia is building that capability and using it to assist the United States.

Economically, any past concern about China using trade coercion for political purposes fades by comparison with the tariff war the Trump administration is now waging against the entire world. The lunacy of this defies any rational explanation, not least because of the harm it is bound to do to the United States’ own economy, and its political standing in the world.

Where has been the beginning of an understanding of the basic principles of comparative advantage and gains that all countries have enjoyed from international trade? What has been the economic logic in calculating so-called ‘reciprocal’ tariffs? If deficits were the rationale, what was the reasoning behind the common tariff of 10 per cent being applied to Australia, with which the United States enjoys a huge trade surplus? And what was the economic logic in applying tariffs on China so high as to amount to a de facto trade embargo, with all that it implied for empty shelves, higher prices and massively disrupted US supply chains?

Even if there is eventually a massive retreat on all these fronts when the scale of its nonsense eventually sinks in, Trump’s ego-driven fecklessness means that even his closest advisers have no idea what will come next, and the costs of this uncertainty to global trade and incomes become more manifest.

There is simply no rational alternative to a cooperative rather than confrontational approach being taken to all our international relationships, and there is ample scope for Australia and China to work together on a multitude of fronts. When it comes to national security, while it makes perfect sense for every country to build a core defensive capability based on worst-case assumptions, by far the best way of achieving sustainable peace is finding security with others rather than against them.

One obvious way for Australia to build a more cooperative relationship with China is to work together on addressing a whole range of global and regional public goods issues — from climate change to nuclear arms control, terrorism to health pandemics, peacekeeping to responding to mass atrocity crimes and defending free trade.

There is particular scope for cooperation on economic and trade issues in the Asia Pacific. Restoring some real traction for leader-level policy dialogue mechanisms like APEC and the East Asia Summit will be important. But perhaps even more immediately useful in promoting closer regional economic integration, and avoiding disintegration of the wider trading system, will be those mechanisms in which the United States has either declined or not been offered a seat at the table — the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

Talk of a 2025 RCEP leaders meeting offers the prospect of a platform for finding common cause on the principles necessary to meet the challenges of Trump’s trade war. The CPTPP is a serious free trade agreement, which would be dramatically further strengthened by China joining, as Beijing applied to do in 2021. The CPTPP’s disciplines on support for state-owned enterprises and labour issues have so far been presented as a barrier to that happening.

But with China wanting to add some shine to its free trade leadership credentials at the time as its great strategic competitor is burning its own, a good place to start might be to address those internal reforms which would clear the way to its membership. Difficult yes, but potentially game changing.

For Australia, keeping its balance as it walks a tightrope between China and the United States is not an enterprise for the diplomatically or politically faint-hearted. The stakes could hardly be higher. But if policymakers can stay calm, there is every chance of success.

This article is a shortened version of an address to the Australia-China Economic Trade and Investment Expo (ACETIE) on 14 August 2025.

Republished from EastAsia Forum, 25 August 2025

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.