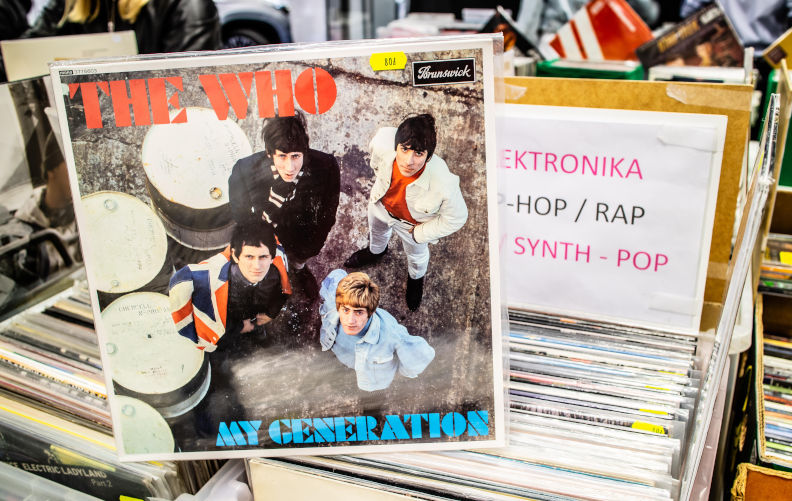

Still talkin’ ’bout My Generation

August 23, 2025

The first time I heard The Who’s My Generation_, I was a teenager and it sounded like a punch in the face._

Pete Townshend’s snarling guitar, Roger Daltrey’s stuttered defiance, and that immortal line ‘’hope I die before I get old”. It felt like the purest youth revolt. It was a declaration that the postwar baby boomers, then kids in their teens and twenties, weren’t going to march quietly into the world their parents had built.

Listening to it again now, decades later, is a jolt of a different kind. The song still crackles with energy, but the generational dynamics it once captured have flipped. Boomers are no longer the rebellious youth dismissed by their elders. They are the elders. And in public debate today, “boomer” is less a demographic label than an accusation: hoarders of property, drivers of inequality, blockers of reform.

That caricature holds some truth, but only some. Yes, a share of the boomer generation rode the property wave, banked the superannuation, and insulated themselves from the insecurities that younger generations now face. They have benefitted from policies that turned housing from a public good into a private asset class, dominated by developers, investors, and speculative capital.

But the longer, more realistic story of the boomers is far more complex. Many never owned a home. Many still rent into retirement. Many spent their lives in low-paid or precarious work, their modest superannuation accounts bearing no resemblance to the stereotype of gilded wealth. And many, perhaps more than we care to admit, never stopped fighting the battles of the 1960s and 70s. They can still be found on picket lines, at environmental blockades, and in the meetings of tenants’ unions and community housing campaigns.

To hear My Generation today is to be reminded of that continuity of struggle. The song’s rage at being misunderstood by the powerful does not belong only to youth; it belongs to anyone who refuses to accept being sidelined. In that sense, the older boomers who never sold out are as much the heirs of the song’s spirit as they were when it first roared from a transistor radio.

If the anthem were reworked now, it would not be a lament for lost youth. It would be a call for solidarity across generations. Instead of “hope I die before I get old”, it might insist “I hope I never give up the fight". It would be directed not against “the old” as such, but against the concentration of wealth, the private developers who have hijacked the housing system, and the politicians who protect them.

That’s the missing verse in the generational debate. The boomers were not a monolith then, and they are not a monolith now. They produced the billionaires and the activists, the landlords and the lifelong renters, the comfortable and the precarious. To lump them all together as privileged is to erase the very people who continue to resist the system that betrayed their youthful hopes as much as it betrays today’s young.

Listening again to The Who after all these years, I hear less a generational anthem than a human one: a refusal to be defined by the prejudices of others, a demand to live authentically, and a warning against complacency. Those themes remain urgent. And perhaps the most radical reworking of My Generation for today is to strip away the generational warfare altogether and point the critique where it belongs, not at those who grew old but never stopped fighting, but at those who profit from keeping us divided.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.