The great dying

August 26, 2025

The heedless march of man has now laid waste to 60% of the planet’s land surface area, putting humanity’s own future at risk, the latest science reports.

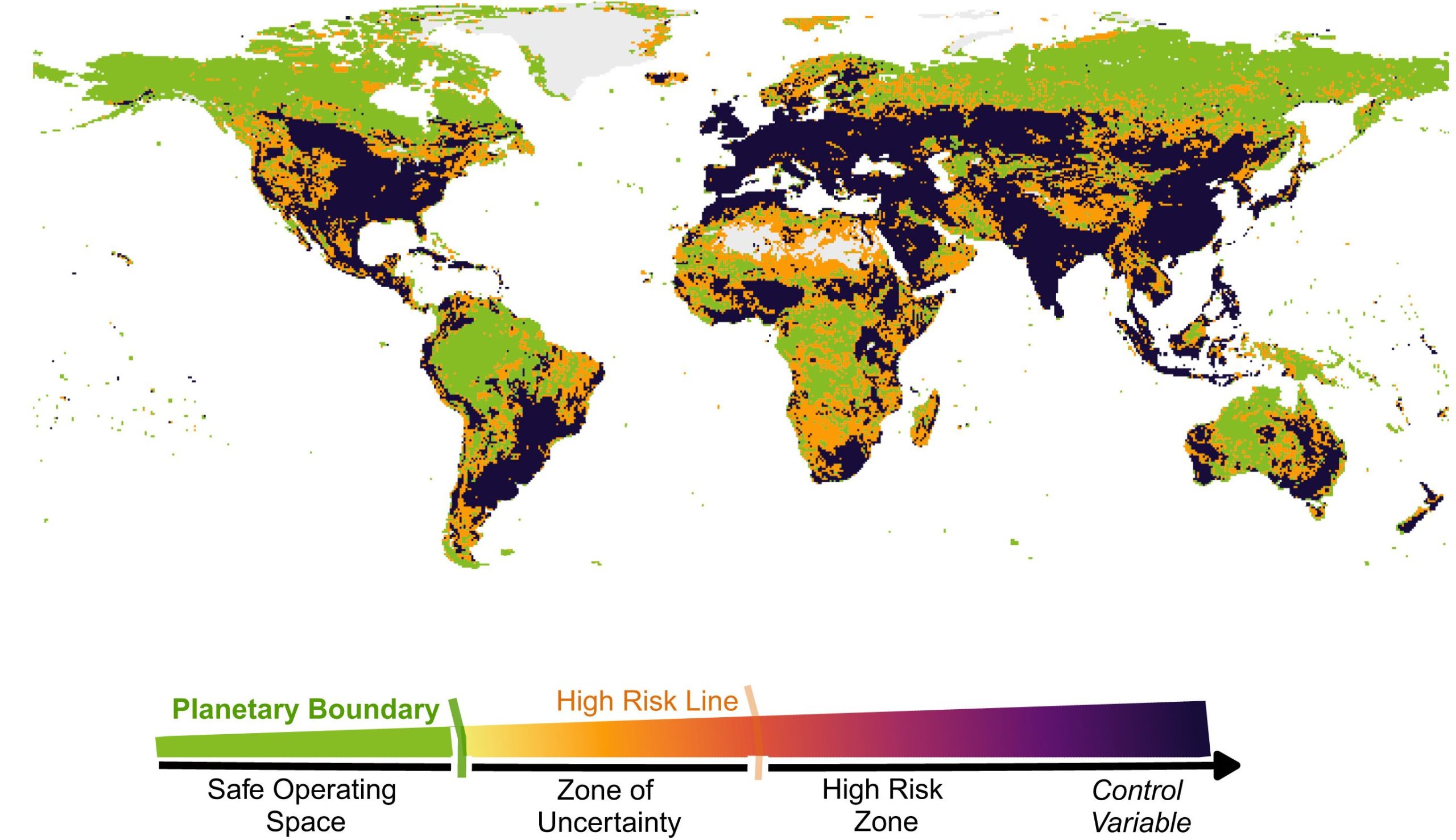

Figure 1 The map shows for the first time the zones of Earth classified as ‘safe’ (green), ‘uncertain’ (orange) and ‘high risk’ (red to dark blue) for life.

According to the Potsdam Institute, the integrity of ecosystems has already been critically compromised across large expanses of the planet. “We find that the local (safe) boundary is currently transgressed on 60% of the global land area, with 38% already at high risk of degradation,” the scientists say.

Put in plain language, those areas of the planet can no longer support the life they once did – and life includes human life.

The remaining, ecologically more intact regions are mainly in deserts, the Arctic and the two remaining major rainforests, the Congo and Amazon – both facing rapid decline.

The map is the first to delineate the regions of Earth where the ability to support both humans and wildlife is failing. It is designed to help classify the life-supporting condition of the landscape so it can be better managed in future – should humans so desire.

One of the primary impacts of the Earth’s collapsing biosphere is the appalling rate of extinction of plants and animals now being observed worldwide. These are extensively documented in an outstanding new book _Before They Vanish_ by biologists Paul Ehrlich, Gerardo Ceballos and Rodolfo Dirzo.

The researchers bring fresh insight to the crisis overwhelming the Earth’s plants and animals, arguing that by the time we notice a species is becoming extinct, it is already too late to do anything meaningful to save it. The clue lies in shrinking animal populations over time, which are the precursor of extinction.

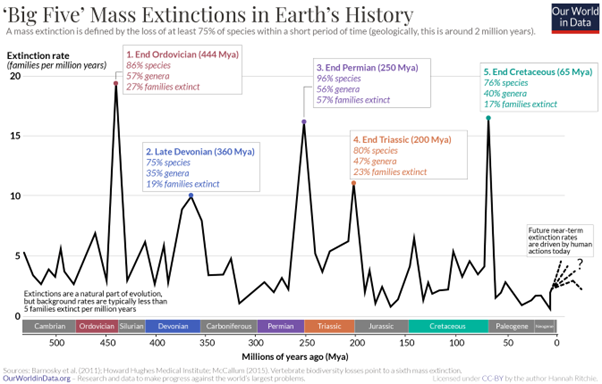

Contrasting events today with the previous five mass extinctions, they state “It is clear these… were a nasty business for the dominant life-forms of their times”, noting that each, in its way, cleared the way for the eventual emergence of H. sapiens by getting rid of big predators and allowing smaller animals to flourish_._ The sixth, however, is a different business.

“For humanity today the ongoing sixth mass extinction is one vast crisis – an existential threat to civilisations, many human populations, or even to our own species,” they say.

At the end of the last Ice Age, the total biomass of animals on Earth was estimated by Vaclav Smil at 300 million tonnes, of which humans (with a population of about four million individuals) constituted a tiny fraction (about 200,000 t, or less than 1%).

By the 2020s, the world’s total vertebrate animal biomass weighed in at a shocking 2040 million tonnes, of which humans and their livestock made up about 99%. Wildlife was reduced to just 1%, or 204mt. The planet is now dominated by two species, cows and humans.

However, that explosion in animal life has come at the price of massive degradation of plant life — in forests, woodlands, grasslands and wetlands — the very feature underlined in the Potsdam Institute’s latest report, quoted above. With current human population and demand growth, this is not reversible, meaning that humans are now destroying the main process that gives life to the planet — photosynthesis, the conversion of sunlight to energy by plants — which supports everything else.

Extinction is rarely sudden. It can take place over big spans of time. Most people think of the Cretaceous-Palaeogene event (66my BP), where an asteroid took out the dinosaurs, as sudden, but in fact only its local effects were catastrophic (firestorms, tsunamis) in the short run. Most of the planet then suffered a global die-off of plant life caused by the heavy dust cloud that darkened the Earth for years afterwards. Animals over 25kg in weight vanished. In places remote from the impact site, the die-off took place over approximately 5000-10,000 years, before plant life recovered and small mammals and birds began to re-occupy the empty landscapes.

Similarly for the Permian-Triassic extinction (251.9 my BP), the worst such event known from the fossil record prior to the current Anthropocene or 6th Extinction. This is thought to have been triggered by a vast volcanic outpouring in Siberia that not only darkened the planet, but also poisoned the oceans and released a massive episode of global warming. A series of pulses eradicated 81% of marine animal species and 70% of land animal species over a period of about 60,000 years.

Many scientists now fear that humans have, unwittingly, triggered a similar sequence of events by releasing tens of millions of years’ worth of stored carbon back into the atmosphere in a matter of a few short decades.

It is the progressive nature of extinction events that means that most people have not yet awoken to the peril we face.

“The size of the world’s population, the nature of our consumption and economies and our use of energy and water resources have combined to threaten our very existence,” explains water scientist Peter Gleick.

Merely feeding humanity now absorbs 40% of the world’s land area – and what’s left is unsuitable for farming. This, in itself, is the biggest driver of extinction of other plants and animals and, as we clear and plough up the habitats they support, we threaten our own futures.

The human assault on the world’s living animals is multi-faceted: land-clearing, over-exploitation, plastic pollution, toxic chemicals, introduced species, climate disruption and corporate greed are among the most lethal drivers, say Ehrlich, Ceballos and Dirzo. “None of these drivers operates in isolation from the others. Extinction events are the result of the(ir) combined effects. This is a dangerous and deadly mistake we cannot afford to keep making.”

The whole of nature is now in decline, they warn – and this has ominous consequences for humans, because of the life-giving services it will deprive us of. These include:

- Primary production, which underpins the entire planetary food chain;

- Production (by plants) of atmospheric oxygen;

- The formation and retention of topsoil;

- The production of the organic chemistry which constitutes life; and

- Recycling of nutrients.

These services, in turn, underpin our ability to obtain food, fresh water, fuel, fibre, medicines, timber and other building materials.

At the same time, they help to regulate the climate, keep the biosphere habitable, cleanse water, limit disease and pollinate plants. As humans, we also derive important cultural and spiritual sustenance from nature, which is now being lost.

Such a destruction of nature has never before been witnessed by humans – and the extinction of species is accelerating it, the scientists state. The Tree of Life, first described by Charles Darwin in 1859, is being mutilated and hewn down.

The root cause of the devastation is “growth mania” – the human lust for ever-increasing numbers and consumption. A lust that a single planet can no longer satisfy, as the breaching of six of the nine planetary boundaries now reveals. This places humanity itself well outside its own safe operating space.

Clearly, the answer is for humans to come to their senses and rein in both their population and material demands, but egged on by selfish corporations, billionaires and toxic capitalism, there seems little chance of this happening. The world could create more wildlife parks – but who will agree to bear the cost? We could educate our young to care for nature – but that will take too long.

Two of the few practical answers to the biodiversity crisis are renewable food – which would see half the Earth returned to nature, and a Stewards of the Earth program in which indigenous people and ex-farmers are funded (from defence budgets) to restore natural ecosystems.

But, as Ehrlich and colleagues remark, “there are no magic bullets”. In the end, humans will only survive if we understand the consequences of our actions – and change our behaviour.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.