Fifty years without coups or dictators: How PNG built a durable democracy based on dignity and fairness

September 17, 2025

On 20 April 1972, 100 newly elected parliamentarians gathered in Port Moresby for the opening of the Third House of Assembly, Papua New Guinea’s legislative body.

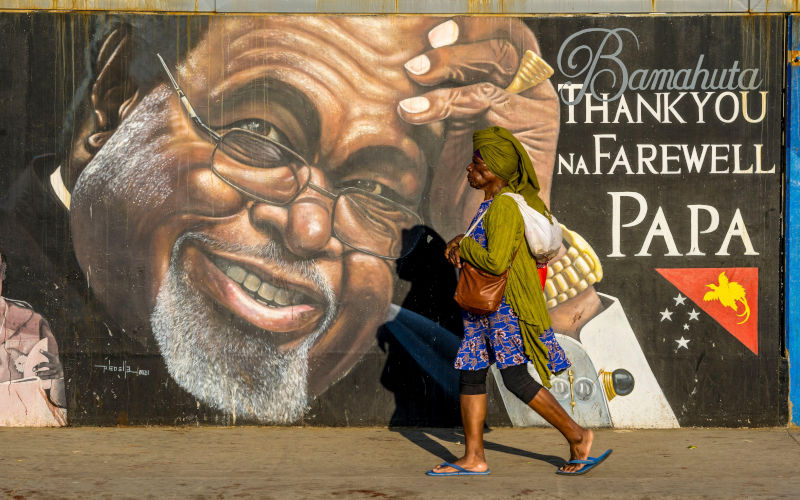

Many of these members were young and some were new to politics: chief minister (later Grand Chief) Michael Somare was 37, minister of finance Julius Chan was 33, and Josephine Abaijah, the only woman, was 32.

Within three years, these trailblazers would steer the country from a colonial territory of Australia to a newly independent nation, declared on 16 September 1975, 50 years ago this week.

As they moved from colony to self-government to independence, the members of the Third House of Assembly held sophisticated debates on decolonisation.

Leaders did not simply inherit Australian institutions. They reimagined them, arguing about land, law, unity, culture and what the concept of “development” should mean in a Melanesian society.

These speeches and debates are captured in Debating the Nation: Speeches from the House of Assembly, 1972–1975, the recently published book we co-edited along with Keimelo Gima, a historian at the University of Papua New Guinea.

The formation of the ‘mother law’

Papua New Guinea prepared for independence with a radical approach to the drafting of its constitution. The task fell to the Constitutional Planning Committee, led in practice by Bougainville priest-politician John Momis.

Over three years, the committee held meetings across the country, gathering the “raw materials” of people’s views on citizenship, governance and development. The result was a constitution known as the “mother law”. It was one of the most inclusive in the world and, in Momis’ words, a truly “home-grown” document.

At its heart was a redefinition of development in the context of PNG. Momis believed progress should not just be measured in gross domestic product and prestige projects, but also in the continuation of the traditional values of PNG – liberally sprinkled with the progressive ideals of the 1970s, which celebrated small-scale societies.

Momis declared that true development was “integral human development” – measured by people’s well-being, not wealth or power.

This was a radical stance in the 1970s. It defined development in terms of human dignity, fairness between regions, grassroots participation and the preservation of cultural and spiritual values. It foreshadowed the “ Melanesian Way”, the celebration of Melanesian communalism developed by another central figure in PNG independence, the esteemed jurist and philosopher Bernard Narokobi.

This concept remains strikingly relevant today. Allan Bird, the governor of East Sepik province, recently invoked the spirit of this philosophy in an address to students at the University of Papua New Guinea’s 60th anniversary symposium last month.

Putting policy into action

If the constitution set out the vision for the nation, the Eight-Point Plan put forth by Somare, who would become the country’s first prime minister, translated it into policy.

It called for Papua New Guinean control of the economy, decentralisation, support for village industries, equal participation for women and self-reliance. Somare warned against foreign dependency and of a “very rich black elite [emerging] here at the expense of village people".

Turning ideals into practice also required new institutions. That task fell in part to Chan, the finance minister, who in 1972 delivered the first budget by a Papua New Guinean — a symbolic moment in the transfer of power.

For Chan, controlling the purse strings was the foundation of self-government, and he insisted the country must “look to its own resources” if it was to pay its own way. Within three years, the Central Bank and the kina were also in place.

Citizenship proved explosive. Many Australians living in the territory feared they would be expelled from an independent PNG and were loud in their demands. Parliamentarians such as Ron Neville urged an open, multi-racial citizenship model to attract investment.

Momis argued, however, that three million Papua New Guineans “had nothing” and needed protection from Australian control. United Party leader Tei Abal rejected dual citizenship for Papua New Guineans and Australians and insisted the law should be “firm, but not racist”.

The eventual compromise — single citizenship, no automatic rights for expatriates, but scope for naturalisation — reflected the balancing act between inclusion and integrity. But if citizenship defined who belonged to the new nation, the harder question was whether the nation itself would hold together.

The trials of decolonisation

Unity was not guaranteed. Secessionist movements such as Abaijah’s Papua Besena, which advocated for an independent Papuan state separate from New Guinea, threatened the territorial integrity of the new nation, but it was not the only threat.

Leaders on the island of Bougainville pushed for their own secession, citing grievances over the Panguna copper mine, which began production in 1972 under a subsidiary run by Rio Tinto.

Somare declared, however, that unity was not up for negotiation. He staved off the disintegration of the nation by introducing provincial governments and a federalised system in the months before independence.

Holding the country together was only part of the challenge. Independence also demanded a deeper transformation – freeing PNG from the colonial institutions and mindsets that still shaped daily life.

As Momis argued in 1974, true freedom was a difficult task when education and the very institutions of nationhood were all created by the colonial regimes, first under the Germans and British, and then the Australians. Decolonisation meant more than simply raising a new flag – it entailed building a society grounded in justice, dignity and local values.

Those ideals still shape PNG today, but they also matter for Australia. PNG’s independence is part of Australia’s story.

When PNG became independent in 1975, many people on both sides of the Torres Strait feared fragmentation or chaos. But despite secessionist pressures and economic challenges, PNG has remained a parliamentary democracy for 50 years: no coups, no military takeovers, no descent into dictatorship.

That outcome was not inevitable. It was the product of hard debates and principled choices in the 1970s. Leaders such as Somare, Chan, Abel, Momis, Abaijah and John Guise fought over unity, land and development – but they fought in parliament, not through violence.

Half a century later, their words still resonate. At the University of Papua New Guinea symposium we attended in August, speaker after speaker referred to the ideals of the founders. They reminded us the constitution was never just a legal framework. It was a profound statement about what development actually means. This is not simply growth, but dignity, participation, fairness and cultural identity.

That is a legacy Australians should not forget.

Postscript from John Menadue

Whitlam in New Guinea before independence.

Whitlam and I visited Papua New Guinea several times. During each visit, he put independence on the public agenda. He was not impressed with the argument that independence would bring disorder and slow development. People are entitled to independence and, with anti-colonial winds blowing everywhere around the world, it was better to grant independence sooner rather than later.

The message was not well received, particularly among the white planters in the New Guinea Highlands. The undercurrent and sometimes the accusation was that by talking independence he was promoting violence and possible bloodshed.

We found Australian Government officials well meaning but paternalistic. We were often taken on inspections of private homes by district commissioners when the owners were away or at work. There was no sense of invasion of their privacy.

Whitlam described such government officials as “third-rate Australians doing a fourth-rate job”. Toilets were for “Marys” and “boys”: indigenous people were non-expatriates.

Disclosure statement Brad Underhill received funding for the “Debating the Nation” book from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

Helen Gardner received funding for Debating the Nation from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

Republished from The Conversation, 15 September 2025

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.