Can we save a 'livable Earth'?

September 13, 2025

In reshaping the world for prosperity, humanity has undermined the very foundations of progress.

So warns the latest study from the World Bank Group, entitled Reboot development: the economics of a liveable planet.

It is the latest in a growing series of global studies to acknowledge that humans have gone too far in exploiting the planet we live on, transgressed its safe boundaries – and must urgently reshape our lives, economy and civilisation if we hope to survive in the long run.

“The very forces that have fuelled economic growth — industrial expansion, energy consumption, and large-scale agriculture — now strain the planet’s ability to sustain this prosperity,” the World Bank cautions.

Air pollution kills and shortens millions of lives every year, with growing impacts on productivity and employment. Water resources, once abundant, are now strained and often tainted by toxic chemicals and industrial waste, also with economic and health impacts.

Forests are falling at frightening rates and the oceans, once thought inexhaustible, are hammered by overfishing, acidification, plastic pollution and spreading dead zones.

“In the pursuit of progress, humanity has destabilised the systems that make prosperity for all possible,” the World Bank warns.

The report is a “road to Damascus” for the World Bank, once a prime disciple of the now anachronistic old-school economics. Over the years, the Bank had a fair bit to do with all that progress, borrowing from wealthy countries to fund accelerated development and modernisation in poorer ones, often to the detriment of the environment. And while much of the real destruction was perpetrated by the rich world making itself richer, the unanticipated global population surge has become a major force in the current devastation of forests, freshwaters, oceans and atmosphere, as people everywhere seek to catch up – and fail to count the cost.

Whether the Earth remains “livable” by humans in the long run depends on the stability, productivity and resilience of its natural resources, the Bank now argues. Without these, the place might resemble Mars or Venus – barren, hostile and uninhabitable, a reality without the benefit of science fiction or Hollywood.

In one of its more shocking statistics, the report reveals that 90% of the human population now live in areas affected by degraded air, water and land. While this is especially true of low-income countries, it is increasingly the case in the affluent world too, as the tide of degradation rolls planet-wide.

By destroying the primary resources on which economic growth depends, humanity has built itself an engine for self-destruction, an economic system that, like the legendary serpent Ourobouros, devours its own tail.

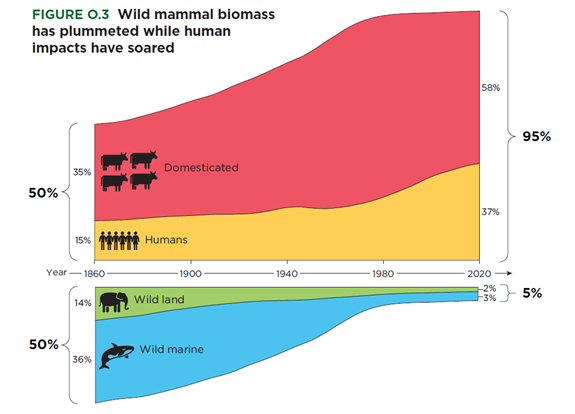

Since the Industrial Revolution, humans have moved from being passive beneficiaries of the Earth’s biosphere, to becoming its dominant exploiters, the Bank now realises. This is nowhere more plain than in the following table, where the wild world has shrunk from half the planet in 1850 to barely 5% today.

Figure 1. Human takeover of the Earth’s biosphere. Source: World Bank, after Greenspoon. 2025

Importantly, the Bank takes on board the warnings of the Stockholm and Potsdam Institutes, that humanity is now living well outside six of the nine safe planetary boundaries – “a situation where human activity is now encroaching on critical thresholds that define the stability of Earth’s systems”.

Increasingly, it is being recognised that the economy “is embedded in nature and cannot exist apart from it”, the Bank says. And, in a backhander to the unreconstructed economics fraternity, “economic models that assume human-made capital can readily replace natural capital fail to capture this reality".

Insightful individuals, from Kenneth Boulding to David Attenborough have observed, “Anyone who thinks that you can have infinite growth in a finite environment is either a madman or an economist.” Unfortunately, the madmen are still in the ascendant, chiefly in the business, industry and banking sectors, but also their handmaidens in university economics and commerce departments.

However, in this latest report, the World Bank has clearly decided to break ranks, to some degree. As to solutions, there exists huge scope for efficiency in a world where nearly a third of all food, a third of all water and two thirds of all energy are wasted, it points out.

But efficiency alone will not prevent disaster. The key lies not only in producing things better, but also in producing better things, the Bank argues. It cites how transitional minerals like lithium, cobalt, nickel and rare earths are paving the way for transformations such as renewable energy to build the electro-economies of the 21st century. But even these have to be extracted without deforestation, biodiversity loss, water, air and soil contamination.

The Bank argues that a shift to a “clean economy” will create more jobs as well as greater opportunity. But that must come on the back of better policies, designed to incentivise the switch to clean production. And good policy, in turn, rests on sound, science-based information, uncontaminated by the lies that entrench many of today’s destructive policies.

“Today, the convergence of unprecedented wealth, abundant data and the transformative power of the digital revolution offers a unique opportunity to chart a different path – one that enhances prosperity while simultaneously minimising environmental harm,” it says.

In summary, the report makes an important acknowledgement that today’s economics have become a formula for disaster. However, the solutions it proffers are only partial, make far too many concessions to the status quo and fail to recognise the larger catastrophe of human overshoot. They do not even mention concepts such as degrowth, rewilding, circular economics or depopulation.

Largely, too, they are market-based, seeming to embrace the idea that the poison can also be the cure.

In other words, they will not solve the crisis the Bank has now envisaged – though they may help feed the conversation we have to have. If is not already too late for that.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.