Devouring the earth may decide our future

September 24, 2025

Every day, the food you eat and resources you use cost the planet at least 12 kilos of lost topsoil.

Estimates of global soil loss vary according to the method used to measure them. They range between 36 billion tonnes (ESDC) and 75 billion tonnes a year (FAO). This article uses the lower estimate.

Twelve kilos of topsoil, 950 litres of water, 1.6 litres of fuel, 0.3g of increasingly toxic pesticides and 4.9 kilos of carbon emissions are what it now takes to feed an average human every day. And there are 8,250,000,000 people on the planet.

Soil loss and resulting food scarcity is fast becoming the biggest unseen threat to the human future. Soil degradation is driven chiefly by farming and grazing, land clearing and forestry, by urban expansion, construction and industrial pollution.

It is the factor most commonly ignored by billionaires, politicians and other shortsighted male leaders calling for population growth to serve their selfish interests. In their ignorance, these boosters are in fact calling for more famine, poverty, pandemics, climate impacts, mass migration, government failures and other consequences of overpopulation.

It is time to recognise that the human jawbone has become the most destructive implement on the planet. It’s devouring soil and water, clearing forests, destroying wildlife and emitting greenhouse gases as never before – but very few people realise it, because long industrial food-chains and supermarkets obscure the damage they inflict from the eyes of consumers. For example, despite the good work of conservation groups seeking to protect the orangutan, the global food industry continues to fell vast swathes of tropical rainforest to grow cheap, unhealthy palm oil.

The mechanics of soil loss mean that, after being disturbed or cleared by humans, most of the soil is then swept away by wind and water. The bad news is that, as the Earth heats and both rain and wind turn more violent, rates of soil erosion are increasing especially in the tropics and drier regions. Eventually, the soil ends up in the deep ocean and is forever lost. Climate is thus a threat multiplier to the existing degradation caused by human activity and the permanent loss of the primary resource that underpins our global food supply.

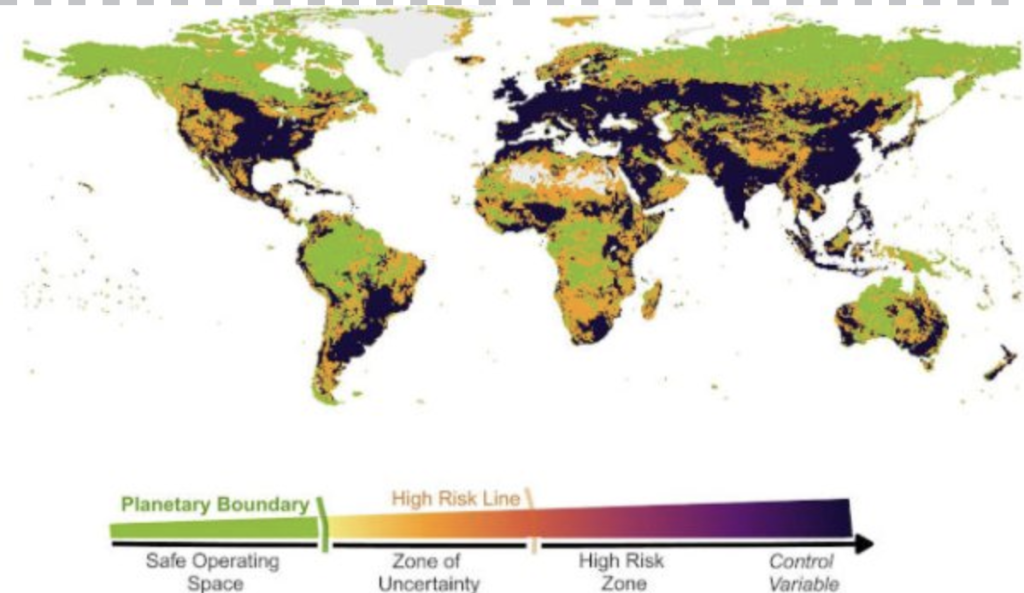

A recent study by the Potsdam Institute found that 60% of the Earth’s land area is now in a precarious state of degradation and, by 2050, this would have grown to 90%. The maps shows the areas of greatest risk.

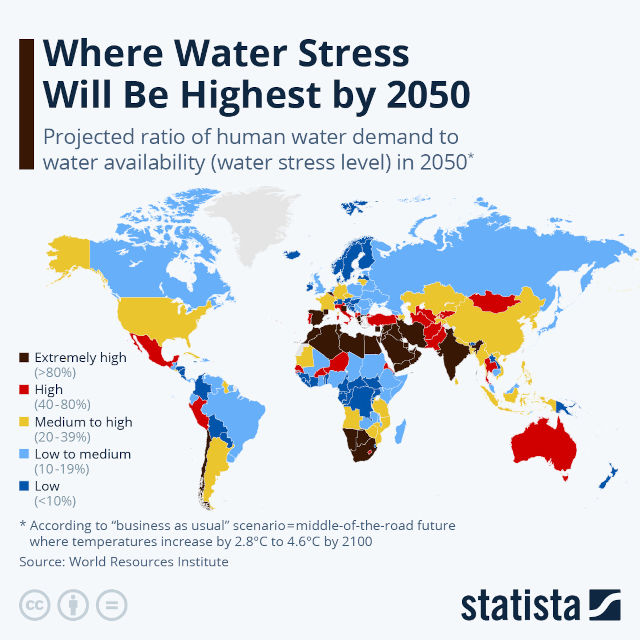

At the same time, world freshwater shortages also loom. The United Nations warns that more than four billion human beings now experience acute water scarcity at least part of the year. Amplified by climate shocks, water scarcity can have a major impact on the global food supply, 40% of which is produced by irrigated agriculture and horticulture, and 60% of which is rainfed and hence vulnerable to climate impacts. In all inhabited continents, the growth of megacities is robbing farmers of the water they need to grow food.

A heated debate has been running worldwide, in science and the media, on the question of whether the human diet should become “meat free”. However, this debate tends to focus on climate impact and to sideline other concerns. A vegetarian diet, for example, may yield fewer greenhouse emissions, but may also cause greater soil erosion, use more pesticides and is highly vulnerable to climate. The solution is to shift the world diet from one reliant on traditional farming methods and towards more "renewable food".

Constrained by the commercial demands of the food industry, the scope of the modern diet is extraordinarily narrow. Humans presently rely on 64 different plant species for food, out of the 30,500 plants rated as edible by science and 300,000+ plant species on the planet. And that does not include sea plants.

This means there is vast scope to diversify and enrich the human diet in ways that do not destroy either soil, water or climate. However, exploring such a profound global dietary change is still in its infancy and the food industry with its focus on money rather than food is indifferent to the possibility, or else ignorant of it.

In coming decades, there could be a boom in local food production, with thousands of novel plant and cell-based foods, in the recycling of water and nutrients in intensive food systems in cities, in the exploitation of soil microbial activity and carbon farming, in the spread of climate-proof production systems such as soilless aquaponics, biocultures, greenhouse cropping, algae farming, “agritecture”, deep ocean aquaculture of plants and fish and in the design of novel diets far healthier, more diverse and less toxic than our present industrial mash-up.

Most human food production will almost certainly have to move indoors or into the deep oceans to avoid catastrophic disruption from heatwaves, droughts, floods, fires, soil and water scarcity – and this entails a no-soil or low-soil system. If the world’s governments fail to hit their climate targets, global temperatures will rise by 3-4 degrees C, far above the levels that farming can tolerate, wiping out traditional food production in many regions.

By transferring the bulk of world food production to cities and the deep oceans, humanity can assure sufficient food for all. It can reverse the 6th Extinction by rewilding up to 24 million sq kms of the planet under the stewardship of farmers and indigenous peoples. Since disputes over food, land and water underlie two-thirds of all wars in the past two centuries, a reliable world food system could also help prevent most conflicts and spread peace.

Creating food is one of the most creative acts which humans perform. How well — or poorly — we do it will decide the fate of our civilisation – and our species.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.