Environment: Arctic and Europe warming at double the global average

September 28, 2025

The Arctic and Europe are melting in the heat. Rapid renewable energy transition for Africa will bring multiple benefits and save money. NSW Planning Commission decides all emissions are significant, no matter how small.

When the world averages +1.5, Europe will be 2.4oC hotter

A few weeks ago I described how the world is getting both hotter and hotter at an increasing rate, how the average global warming for 2023 and 2024 combined exceeded 1.5oC (compared with the average for 1850-1900), and how the world’s carbon budget for keeping the official measure of warming under 1.5oC will be completely spent by October 2027. The focus was on global averages but different parts of the world are experiencing different levels and different rates of warming. To illustrate, because land absorbs heat more quickly than water, the temperature over land is higher than over the oceans, and wind patterns and the proximity of extensive tree cover can lead to regional differences

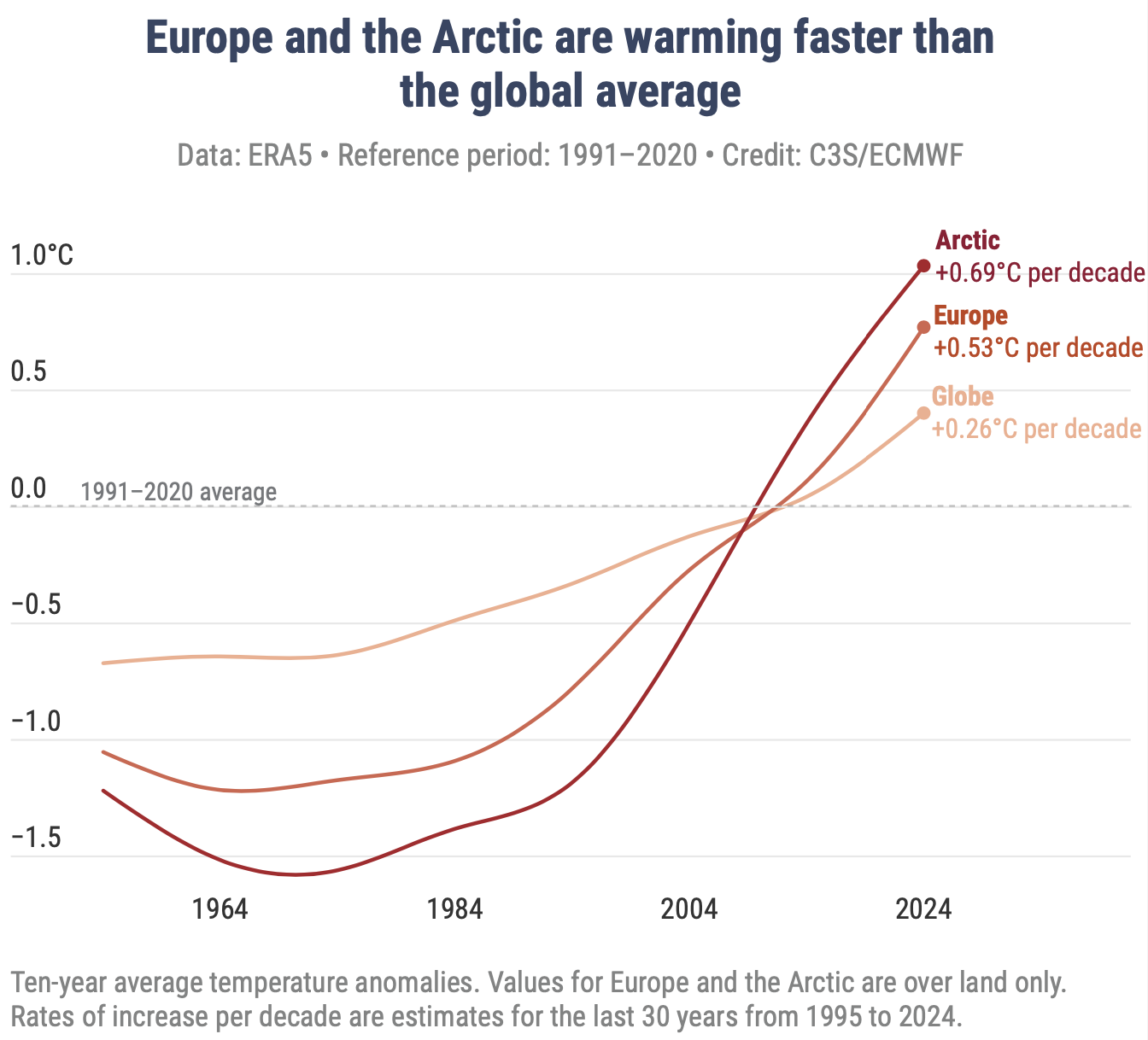

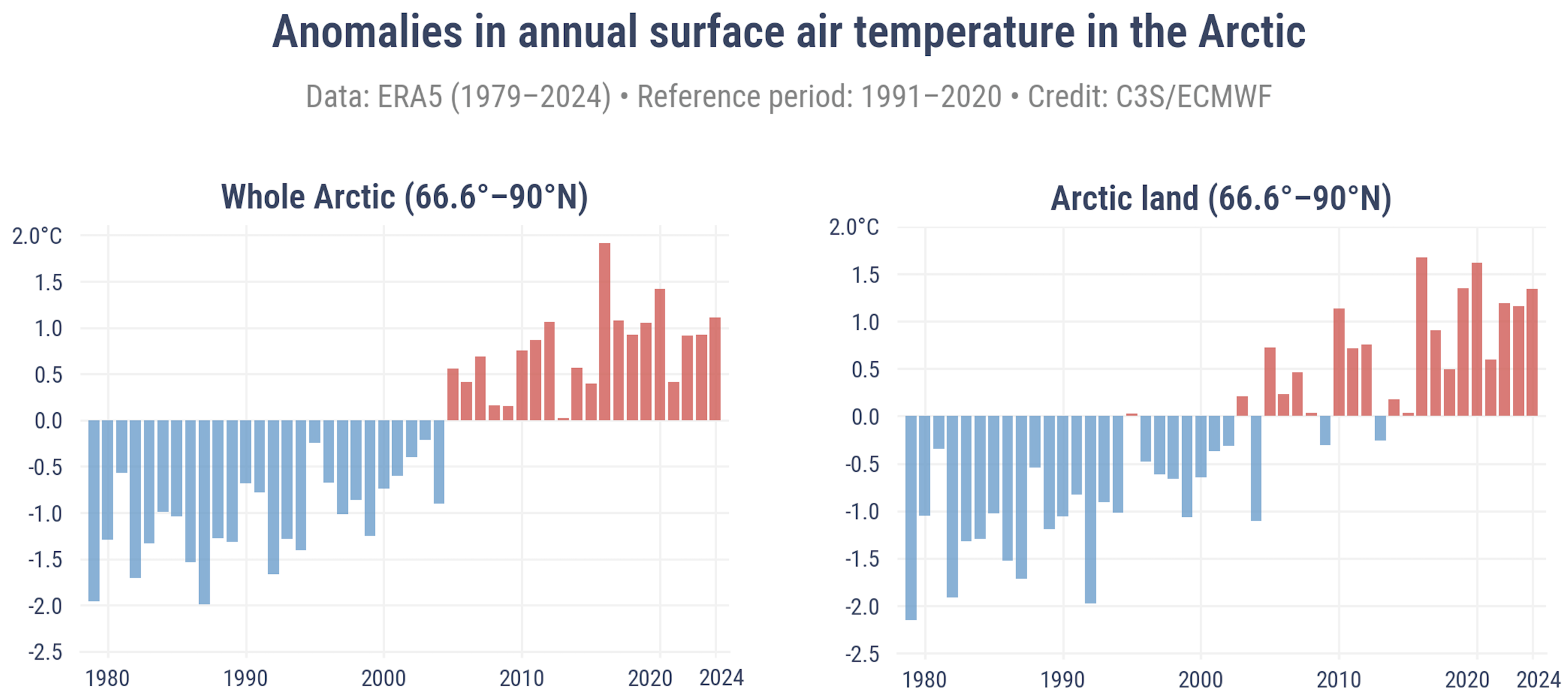

Europe and the Arctic have warmed the most over the last 30 years and their rate of warming has been more than double the global average of 0.26oC per decade. (Note that in the graphs below the reference period for the warming comparisons is 1991-2020.)

The average global warming will exceed 1.5oC (compared with 1850-1900) sometime in the near future. When it does, the warming in Europe will be 2.4oC and in the Arctic 3.3oC. Why?

Europe’s rapid warming seems to be attributable to three main factors:

- Shifts in atmospheric circulation patterns have caused more frequent and more intense heatwaves in summer.

- Air pollution from fossil fuels burnt for domestic and industrial activities block solar energy reaching the Earth’s surface. Progressively since the 1950s, European countries have reduced their very high levels of air pollution. This has been excellent for people’s respiratory and cardiovascular health, but not so good for regional warming as more solar energy hits the land and is absorbed.

- Parts of Europe extend into the Arctic, the fastest warming region on Earth.

The Arctic’s rapid warming (“Arctic amplification”) is caused by several interconnecting factors:

- As the Earth warms, highly reflective polar ice melts to reveal darker ocean and land which absorb more solar energy. This sets up a positive feedback loop or vicious cycle.

- In cold regions, the air near the ground warms faster than the air higher in the atmosphere and …

- … because the Arctic is cold (even with warming, the average temperature is still a nippy -11.4oC), the convection currents created by warm air rising are very weak compared with the tropics. So the warmer surface air stagnates near the Arctic surface and accelerates the warming.

- Atmospheric circulation patterns move warm moist air from the tropics to the poles. Global warming creates warmer air in the tropics and warmer air holds more moisture, so more water vapour is transported to the poles and intensifies Arctic warming.

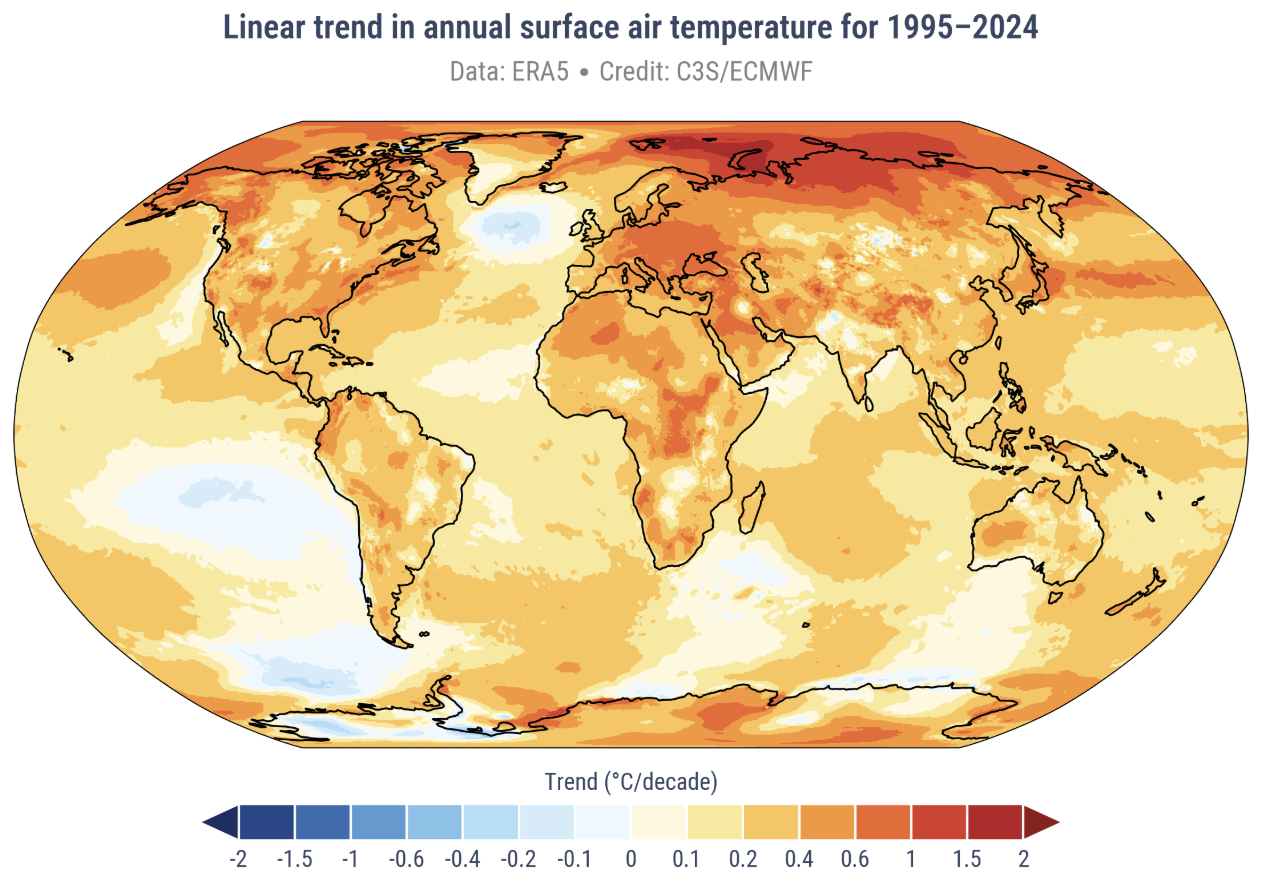

As demonstrated in the map below, as well as the Arctic and Central and Eastern Europe, high warming is seen in the Antarctic, the Middle East and Central Africa. Very few areas, mainly in the oceans, have experienced any significant cooling over the last 30 years.

As a broad generalisation, colder places (e.g., higher altitudes and latitudes) and colder times (e.g., winter and night) are warming more than elsewhere and elsewhen.

100% renewable Africa by 2050

In the relatively few good news stories that I tell, there’s nearly always a comment along the lines of “Africa is missing out on this bonanza”.

Africa faces the triple challenges of high vulnerability to climate change, low energy access (600 million people live without reliable, affordable access to electricity) and poor social and economic development. The good news is that because the three are interconnected, a 100% renewable energy system could tackle them all together.

A recent report, co-produced by the University of Technology Sydney, demonstrates that Africa has an unprecedented opportunity to leapfrog dirty and obsolete energy systems and utilise its large untapped potential for renewable energy, particularly solar, to meet the continent’s needs. The construction of a 100% renewable energy system by 2050 would be consistent with limiting global warming to 1.5oC and would be compatible with universal access to affordable energy. It would also create 2.2 million more jobs than a business-as-usual slower transition, sustainable economic growth and development, and considerable health benefits. Compared with a business-as-usual approach, it would save US$3-5 trillion by 2050.

The structural barriers to Africa’s clean energy transition include a lack of food and energy sovereignty, weak currencies, trade deficits and a lack of access to finance and debt, all compounded by vested interests trying to block African nations’ independence, economic development and energy transition.

Central to the success of the transition are African voices, leadership, ownership and agency in the energy initiatives, with policies and actions driven by local realities rather than external interests.

The report concludes that, “A new model of people-centred development is needed in place of an economy based on the extraction of capital and natural resources. At the international level, this requires debt cancellation and reform of the financial system, alongside scaled up public climate and development finance. Regional policies could help build industrial capacity in Africa alongside national and local governance reforms to support decentralised renewable energy development, including through guarantees and feed-in tariffs.”

Emissions, there are never too few to matter

Redbank Power Station in the NSW Hunter Valley burned up to 700,000 tonnes of coal per year to produce electricity between 2001 and 2014 when the company was placed in administration with debts of $192 million and the power station was mothballed.

In July 2025, the NSW Department of Planning referred to the NSW Independent Planning Commission a request for Redbank to be restarted using 700,000 tonnes per year of dry biomass (vegetation, including energy crops, residues and waste). The proponents claimed that the project would require a capital investment of almost $71 million and would generate up to 330 construction jobs and 60 operational jobs.

The NSW Planning Department calculated that the power station’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions would be 1.3 million tonnes of CO2 per year and this would amount to approximately 0.1% of the total NSW emissions by 2050. However, the Department’s Assessment Report concluded that “the Project would result in benefits to the State of New South Wales, is in the public interest and is approvable, subject to recommended conditions of consent”.

While reviewing the application, the Commission received 591 submissions, with 95% objecting to the project. Public submissions expressed considerable concern about the risks to biodiversity from increased land clearing to produce the required biomass and the GHG emissions associated with transporting and burning the biomass.

In September, the Commission refused the application, focusing on two issues. First, the Commission had concerns about the likely environmental impacts of the proposed sources of biomass which were “not able to be adequately addressed through conditions of consent”.

Second, and very significantly, the Commission considered the project’s GHG emissions in the context of both the NSW Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 and the Climate Change (Net Zero Future) Act 2023 and concluded that:

“[0.1% of NSW’s GHG emissions by 2050] does not render the impact immaterial. As the development assessment regime in NSW considers each project individually, every project under assessment will typically make what appears to be a statistically immaterial contribution to NSW emissions. To take the Project’s contributions to NSW emissions as dispositive of GHG emissions as a consideration in approving the Project would undermine the guiding principle of the Climate Change Act. Given that guiding principle [a critical need to act to address climate change], even a 0.1% contribution to emissions cannot be dismissed as immaterial.”

This is a startling and much-needed change of approach to assessing the environmental consequences of each individual planning application, particularly in light of the Department of Planning’s favourable conclusion. The decision is significant in at least two ways. It recognises the necessity of considering the cumulative effects on the environment and society of all relevant activities, not only those of the project application being considered. Second, it recognises the importance of every incremental insult to the environment no matter its size. If every fraction of a degree matters, it is only logical that every tonne of greenhouse gas matters.

It is advances such as this in the application of laws that frighten the fossil fuel industries and their promoters in parliament and stoke their resistance to the goal of net zero emissions. What will net zero ever give us?, they scream. Well … apart from fewer heatwaves, more secure water and food supplies, fewer category 4 and 5 cyclones, fewer infectious diseases and deaths, financial savings, fewer bushfires, more jobs, less river and coastal flooding, fewer bleachings of the Great Barrier Reef, less damage to coastal properties and infrastructure, healthier ecosystems … not much, I don’t suppose. (Nod here to The People’s Front of Judea, of course.)

Climate-resilient corals around Philippines island

More than 80% of the world’s coral reefs have suffered bleaching and death from higher ocean temperatures. The reefs around the Philippines have mostly not been spared but those around Panaon Island seem to be particularly tolerant of warmer water and have flourished and retained their biodiversity and vibrancy.

The Philippines government has now designated 520 square kilometres of coastal water around the island as the Panaon Island Protected Seascape.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.