Environment: Earth is getting hotter faster thanks to humans

September 14, 2025

We’ll look back on 2024 as the year we sailed passed 1.5. Marine heatwaves in 2024 and 2025 seriously damaged the Great Barrier Reef, again. Insufficient land and money to create enough new forests to offset carbon emissions. Iceland sends a letter to the future.

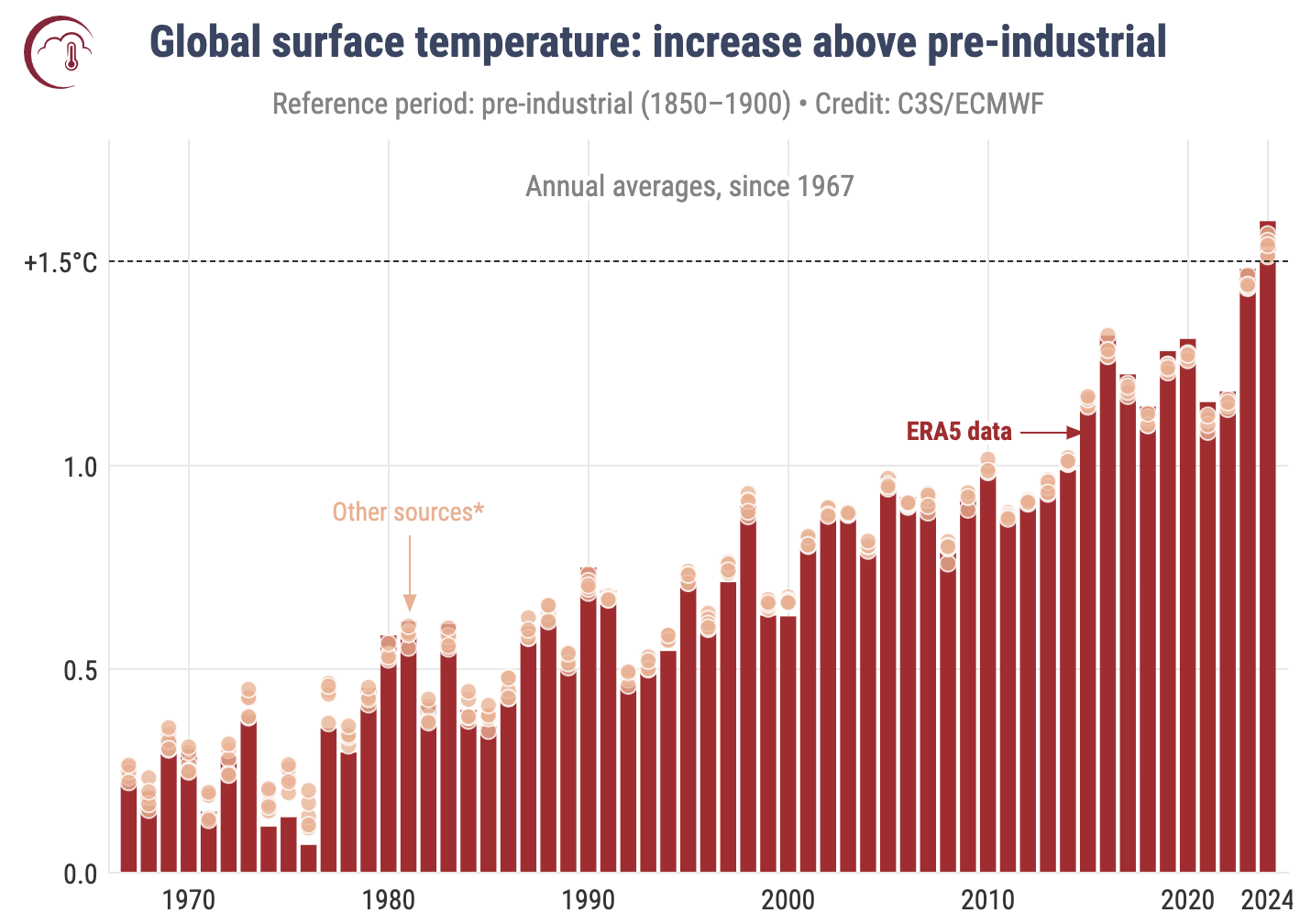

We’re getting hotter faster and are already past 1.5oC

The year 2024 was the warmest on record. The global average temperature was 1.6oC higher than the pre-industrial level (defined as the average for 1850-1900). The last 10 years have been the warmest 10 on record.

The averages for 11 individual months during 2024 were all above 1.5oC (as were the averages for 75% of the days). Although 2024 was the first calendar year when the average temperature exceeded 1.5oC, the combined average for 2023 (the previous warmest year on record) and 2024 was 1.54oC higher than the pre-industrial level.

And yet, officially the temperature increase has not exceeded the now widely accepted target of keeping global warming below 1.5oC if we want to avoid the most severe impacts of climate change. This is because the standard method for summarising the temperature change is to take the average over 20 or 30 years, not one or two or even five.

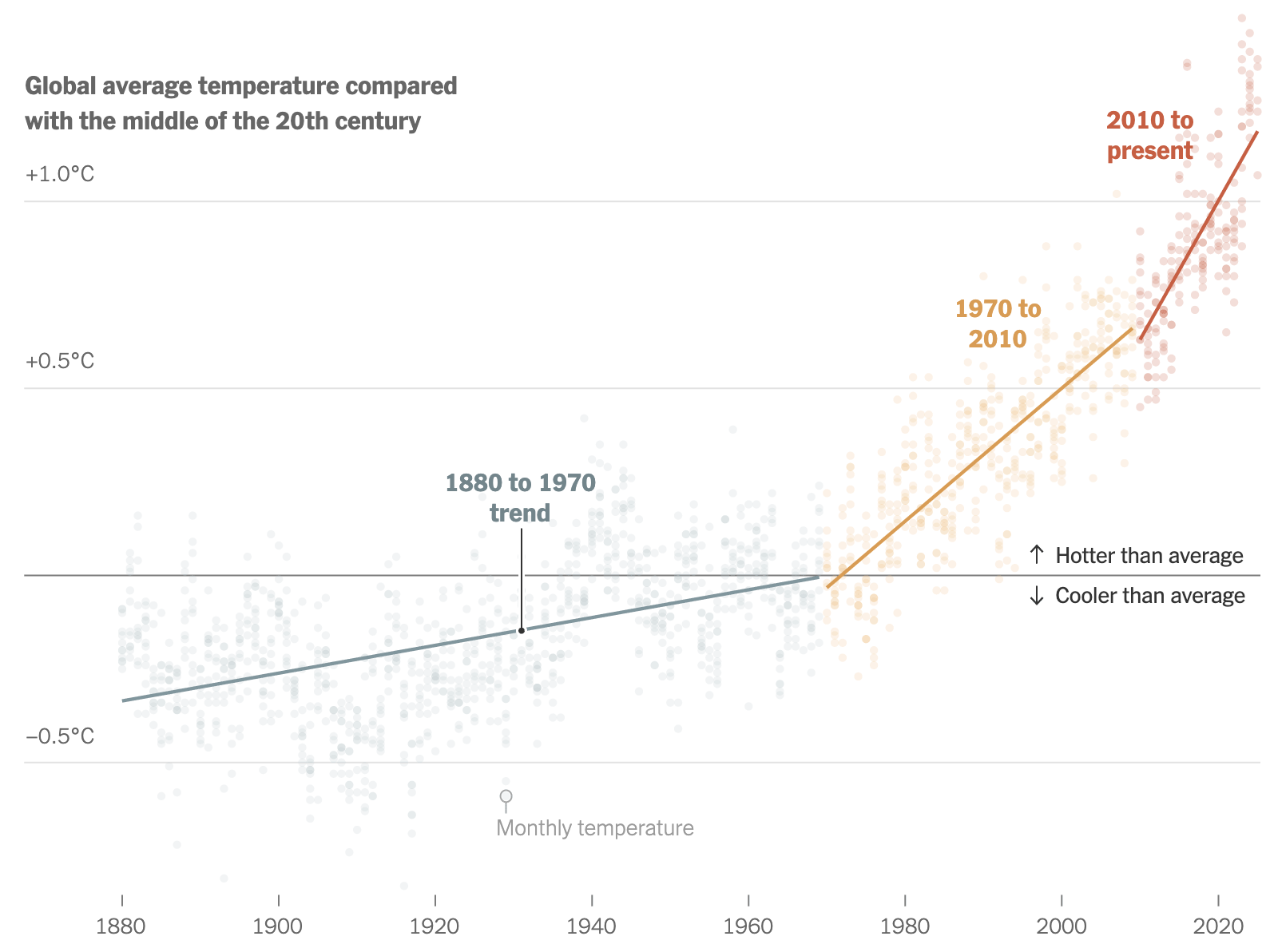

The average over 20-30 years is fine when the average for each year within the time period is oscillating around a reasonably stable long-term average. But it’s not so good when matters are changing rapidly in a constant direction. This is well illustrated in the graph below which shows the trend in global warming (compared this time with the average temperature between 1951 and 1980) during three time periods: 1880-1970, 1970-2010 and 2010 to the present.

It is patently clear that the rate of warming has been increasing in an exponential way and in recent decades the average warming has been about 0.27oC per decade. At this rate, even the official longer-term average will probably exceed 1.5oC in the 2030s, and there’s an almost 50% chance that the five-year average will exceed the 1850-1900 average by 1.5oC before 2029.

As an aside, I think you can make a case that it would have been even more instructive to split the first time period into two: 1880-1930 when the trend was flat and 1930-1970 when the temperature increase began. Indeed, when I look at other graphs and datasets, it seems pretty obvious that between 1850 and 1925 there was no real change in the average global temperature but since then the temperature has been increasing relentlessly.

At the beginning of 2024, the carbon budget for a 50-50 chance of keeping the 20- or 30-year average global warming under 1.5oC was 200 Gt CO2e. With current annual greenhouse gas emissions of 53 Gt CO2e, the budget will be all gone by October 2027, just 25 months away.

While there are many influences on each year’s average temperature, research indicates that 2023 and 2024 were exceptionally warm because of accelerating human-induced warming.

My point is that, to all intents and purposes, global warming has now exceeded 1.5oC because that is what we are experiencing on a day-to-day, month-to-month, year-to-year basis (over the land, warming is now 1.8oC). While every year in the next 10 may not be warmer than the previous one, the failure of governments and corporations to act in accordance with keeping warming under 1.5oC makes it hard to believe that the rate of warming is going to decrease any time soon. As for global cooling, which is what we urgently need, that is but a dream.

The real frustration is that climate scientists have been predicting for years what we are now experiencing. But you shouldn’t believe rigorously produced evidence, should you?

I have focused here on the average global temperature, but there are also variations around the world. I’ll discuss those another week.

Coral bleaching on the Reef in 2024

The Australian Institute of Marine Science has produced a short article and a 4.5-minute video that provide very informative and easy to follow updates on the enormous damage done to the Great Barrier Reef by high water temperatures during the summer of 2024.

Briefly, monitoring of 124 reefs along the whole length of the GBR has demonstrated record losses of live coral cover (up to a quarter on some reefs) in the Northern (north of Cooktown) and Southern (south of Mackay) Regions of the Reef. The GBR also suffered heat stress during the 2025 summer, although not as bad as in 2024.

In recent years, the Reef has also been damaged by cyclones, outflow of river sediment following floods, Crown of Thorns starfish (now called sea stars, by the way) and disease, but AIMS is clear that the greatest threat to the GBR is climate change and that the action most urgently needed is emissions reduction.

Is it realistic to create new forests to offset fossil fuel carbon emissions?

Afforestation refers to the planting of forests where forests have not previously existed – for instance on grasslands, wetlands or even deserts. (Reforestation refers to planting trees where forests did previously exist.)

Afforestation is frequently proposed by fossil fuel companies and governments as a way of removing CO2 from the atmosphere (sometime called negative emissions) to tackle the world’s climate change crisis. Even the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change sees carbon removal as an essential element of the global response to rising concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere. At present, afforestation is the cheapest carbon offsetting technology and the primary method used by commercial offset brokers to provide greenhouse gas polluters with a fig leaf for their ongoing destruction of the environment.

But how much land would be needed for afforestation to offset a) the historical 1732 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent greenhouse gases (1732 GtCO2e) generated by humans, and b) the 673 GtCO2e of emissions that would be released by burning the fossil fuel reserves of the 200 fossil fuel companies with the largest reserves?

The two maps below show (top) the area of land that would be needed for afforestation to offset by 2050 the future emissions from fossil fuel reserves and (bottom) the area of land that would be needed to offset historical human emissions. To offset both groups of emissions, the maps’ blue areas must be added together, which would leave just Asia and Australia grey.

The blue areas represent simply the amount of land needed. There is no suggestion that the actual areas marked represent land that could be afforested. To begin with, of the world’s total land area, glaciers and barren land cover 30% and a further 25% is already forested. Much of the rest is farmland, some of which could be afforested provided care was taken to avoid compromising food supplies. On top of all that, forests don’t grow anywhere; nutrient availability, water supply, soil suitability and climatic conditions all need to be considered. Afforestation also presents serious threats to existing ecosystems and biodiversity, and, as global temperatures rise and conditions get drier, forests are increasingly at risk of severe bushfires.

The study authors emphasise they are not suggesting that forest conservation and restoration should not be a policy objective. Forests have critical roles in sequestering carbon, conserving biodiversity and maintaining ecological functions that are essential for achieving a sustainable future for life on Earth. They are simply trying to demonstrate that afforestation has many practical problems and limits on what it can achieve. The priority should be on emissions reductions not “naïve offsetting”.

A second aspect of the study was to assess the financial viability of fossil fuel companies using afforestation to offset the future emissions from burning their reserves. Without going into the details, the authors estimate that if the cost of offsetting exceeds US$150 per tonne of CO2, all 200 companies would have negative market valuations and the total cost would be almost US$11 trillion, almost US$3 trillion more than their current market value. Current estimates of the social cost of carbon are in the US$180-190 range.

Turning briefly to the area of land that is available globally for reforestation, a separate study has demonstrated that this is 70-90% less than previously estimated and that the reduced area would sequester each year about 5% of the emissions from fossil fuel use and land use change in 2022.

What this all boils down to is that even if carbon credits and offsetting were a good idea that could be implemented well (it isn’t and it can’t), there isn’t enough land or money to make it an effective strategy for combatting climate change.

Vote 1 Slime Mould, the brainless but motivated party

They look like fungi, behave similarly to fungi and live where fungi live, but they aren’t fungi. Nor are they animals or plants. They are slime moulds, a form of protozoa (single-celled organisms with nuclei, think amoebae) called myxomycetes that band together to solve their food security problems. Slime moulds are essential to ecosystems throughout the world, helping organic matter to decay and being eaten by slugs and small insects. Most remarkably, they move around in a deliberate (not random) way and have a sort of memory. How long they’ve been around isn’t very clear, at least 100 million years and maybe billions.

If you’d like to learn a little more and be intrigued by the way slime moulds get about, this five-minute video does a decent job – YouTube is full of videos about slime moulds.

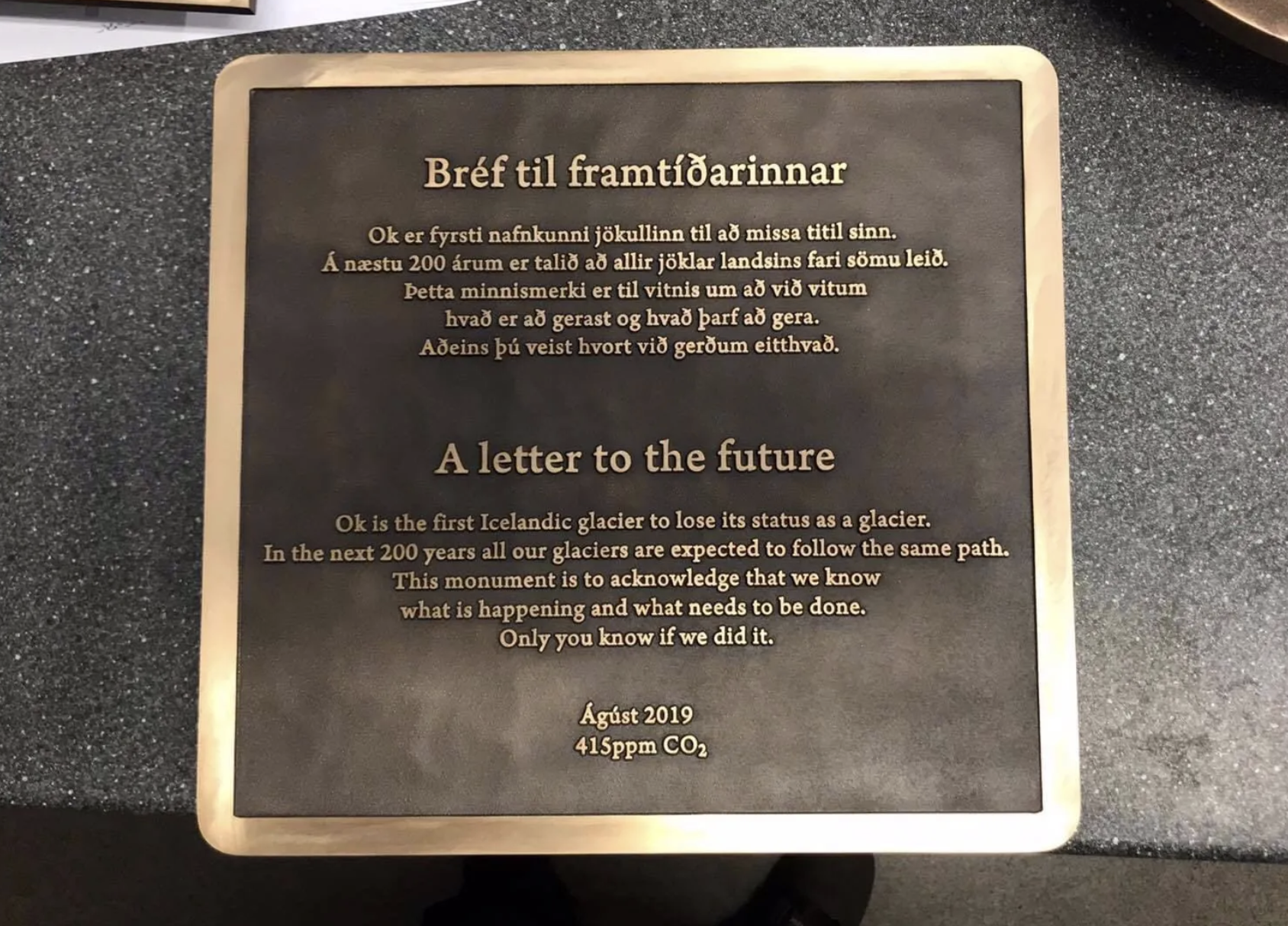

Iceland sends a letter to the future

In 2014, Okjökull lost its jökull and was officially renamed Ok – and it’s no laughing matter.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.