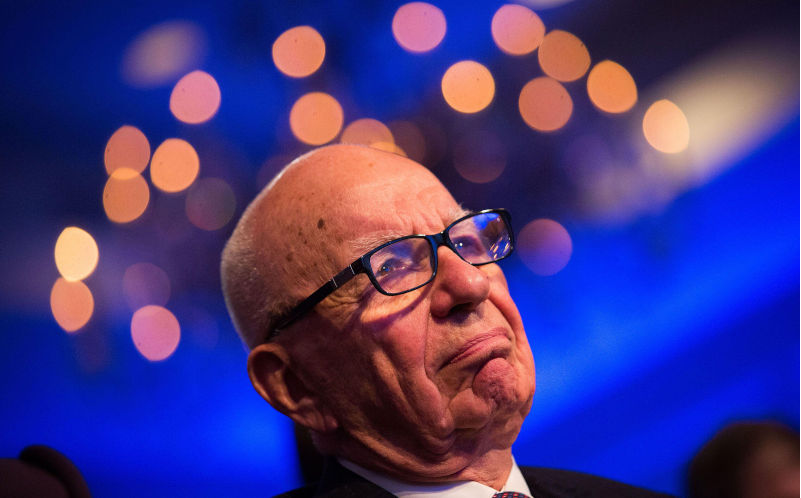

Rupert Murdoch’s greatest scoop

September 12, 2025

On Wednesday 25 February 1976, The Australian published a sensational front page story headlined “Iraq promises $US500,000 to pay Labor’s debts/Whitlam in secret Arab election deal”.

The story dominated Australian politics for the next few weeks, created lasting schisms in the Labor Party, and almost ended former prime minister Gough Whitlam’s career. It was bylined a “Special Correspondent”. That correspondent was in fact Rupert Murdoch filing from London.

This bizarre and unique episode is the only case of a major Australian political party seeking funds from a foreign government, and not just any foreign government but a brutal, authoritarian one, later to be led by the murderous Saddam Hussein.

It was born out of Labor’s desperation. After the governor-general’s dismissal of the Whitlam Government on 11 November 1975, Labor was faced with fighting its third federal election campaign in three years, facing almost certain defeat amid the economic upheavals of stagflation, and hopelessly short of funds.

After a national executive meeting on 16 November, the left-wing Victorian senator, Bill Hartley, approached National Secretary David Combe with the idea that there could be funds available from Arab sources with no strings attached. Combe put it to Whitlam who approved the idea.

Hartley then approached Henri Fischer, with whom he apparently had a friendship and who had good sources in Iraq. Fischer (extreme right-wing and racist) and Hartley (extreme left-wing) were polar opposites politically, but both shared pro-Palestine/anti-Israel views.

Fischer left for Baghdad. On 10 December, three days before the election, two “gun toting” Arabs met Whitlam and Combe in Fischer’s Sydney apartment. The Iraqis promised half a million US dollars from the Baath regime. On the basis of this promise, Combe authorised more last-minute advertising.

After Labor’s overwhelming defeat, morale in the party was very low. To make matters even worse, no money arrived. Combe and others were increasingly desperate as Labor’s advertising agency was threatened with bankruptcy, unable to pay for the extra advertising the party had ordered on the basis of the promise.

News of the staggering proposal reached more people in the ALP, and alarm spread in Labor’s senior circles. Australia’s leading political journalist, Laurie Oakes, became aware of what had occurred and, on the same day as The Australian, the Sun published the sensational story.

Like all such spectacular leaks, there was much speculation about Oakes’ source. Senior Labor figures, such as Combe and John Ducker, were convinced who the source was, and soon after Ducker forced NSW general secretary, Geoff Cahill, out of his job, although Oakes maintains that Cahill was not his source.

After these stories appeared, controversy raged. Initially, it seemed as if the pressure for Whitlam to resign was overwhelming, but his survival was inadvertently helped by prime minister Malcolm Fraser and Murdoch. Fraser, in briefing journalists, said wrongly that Labor had already received the money, and called in the Commonwealth Police to investigate.

Ironically, one of the victims of the controversy was Labor’s national chair Bob Hawke. Hawke had been shocked by the impropriety and folly of the exercise, but conducted the party’s internal inquiry with decorum and fairness. Just before the crucial executive meeting, he made what he thought were unattributable comments, but The Australian headline read “It’s The End For Whitlam”, while an accompanying story said there had been an increase in support for Hawke to become leader. The headline in Sydney’s morning tabloid, the Daily Telegraph, was “Hawke to Axe Whitlam”. Whitlam’s staff made many copies of this story, and distributed them widely. In the words of Hawke’s biographer Blanche D’Alpuget, Whitlam “suddenly was the very image of pathos: sacked as prime minister and now to be sacked as leader of the Opposition’, still the victim of overkill by the Murdoch press and the new Liberal Government. The surge of sympathy allowed him to survive.

Murdoch’s story had come from a very different — and more fascinating and puzzling route — than Oakes’. His main source was Labor’s ill-chosen intermediary Henri Fischer. (The best reference on Murdoch’s dealings with Fischer is Thomas Kiernan’s book Citizen Murdoch. Then a New York resident and friend of Murdoch, Kiernan’s grasp of Australian politics, is to put it kindly, uncertain. But he writes with much more detail than other observers on Murdoch and Fischer and it seems as if this came principally from Murdoch himself.)

According to the file that Murdoch kept, Fischer called him on 17 February 1976 and told Murdoch that he possessed information that would finish Whitlam in Australian politics. Three days later they met in London. Fischer claimed he had a long-standing close connection with the Iraqi Government, and that he knew Whitlam well. He told Murdoch of his meeting before the election with the Iraqis and Whitlam and Combe, where the half-million-dollar contribution was promised.

Fischer claimed that now, two months after the election, there was a furious dispute, with Labor demanding the money and Iraqis saying no, because you lost the election. Fischer said that both sides, especially the Iraqis, were blaming him, and he feared they wanted to kill him.

Murdoch agreed to give him a bodyguard.

There next developed a bizarre sideshow. Fischer told Murdoch one of those he feared most was a man named Tito Howard, who was known, Fischer said, to do dirty work for Arab dictators. Shortly after this, Murdoch received a call from Tito Howard, who asked to meet him on a confidential matter. At the meeting, Howard said he could produce a video of an Australian politician engaging in a major indiscretion, and asked if Murdoch would pay him for it. Murdoch said he would be interested if it stood up, but never saw Howard again.

Murdoch thought that Howard’s appearance increased Fischer’s credibility; that Howard was fishing for clues about Fischer.

When both Oakes’ and Murdoch’s stories appeared on the same day, there was great speculation about whether it was simply coincidence, or that Murdoch had been tipped off that Oakes was about to publish. Now, decades later, with various archives open, the explanation is, almost certainly, that Fraser’s office advised Murdoch that Oakes’ story was about to appear. After meeting Fischer, Murdoch immediately rang Fraser seeking confirmation of Fischer’s story where possible, and kept Fraser informed of subsequent developments.

After Oakes approached Fraser for comment, it seems that Fraser told Murdoch, who then madly finished his article. So The Australian appeared some hours late that night, but matching its competitor’s dramatic headline.

Murdoch’s story did not mention Fischer, but his name entered the public domain almost a week later. Soon after this, Fischer insisted that he urgently needed to fly back to Australia, and Murdoch supplied him with a bodyguard, Douglas Sinclair. But then came Murdoch’s first big problem. Fischer also said he had urgent business in Singapore, so he and Sinclair stayed at the Singapore Hilton. However, next morning, Sinclair found that Fischer had disappeared. A Hilton staff member said Fischer and someone resembling Tito Howard had left very early that morning.

Sinclair was in some distress over the disappearance of the man he was meant to be protecting. He talked freely to The Age correspondent based in Singapore, Michael Richardson. Murdoch, who had no correspondent in Southeast Asia, had to read his competitor’s exclusive material based on interviews with someone on his own payroll.

A week or so later a British journalist in America found Howard, who regaled him with what seems a completely fanciful story: that Fischer had been kidnapped, that he had let Howard know this in London and so Howard followed him to Singapore. Then, he and a kung fu master had overpowered Sinclair and rescued Fischer.

Murdoch’s other problem was that although Fischer’s central claim about the ALP and Iraqi money was accurate, he embellished it with several false details: for example, that Whitlam had agreed to pass on secrets about US talks with Middle East leaders, that he said his government had been influenced by Zionists, that Hawke would never be Labor leader, and so forth.

As a result of Murdoch including such errors, Whitlam was able to sue for defamation, and won a payout described as a six-figure sum. Murdoch might well have considered this money well spent. His papers were the centre of attention in Australia, and, although Whitlam survived, the affair ensured he was even more of a lame duck leader than ever, and the Labor Party was feeling hopeless and divided.

What no Australian politician or journalist seems to have done is follow the money. After Fischer disappears from Singapore, so does any sign of the half-million dollars.

Contrary to what Fischer told Murdoch, the Iraqis had sent the money, probably to an account in Hong Kong, from where Fischer was meant to forward it to the ALP. Instead, he absconded with it.

David Greason, an investigative reporter for the Australia-Israel Review, was the first to disclose that Fischer had stolen the half-million dollars, that he had bought land and settled in California, and was active there in far right-wing politics. In the years since, others, such as Philip Dorling, have reached the same conclusion.

Fischer’s theft raises questions about when did he decide to do it, and how much of his various claims in the lead-up to his disappearance are to be believed. For example, in telephone calls to David Combe he seemed in “a very emotional state” and said several things which made no sense to the national secretary. But was this fear genuine or contrived? Was he simply out to mislead Combe?

Given that Fischer and Howard seem to have disappeared together, it is likely they were already in league with each other, when they both met Murdoch in London. Why, then, did Fischer seek out Murdoch? Was it genuine fear, or was it part of his plan? Was he aiming to stir up controversy in Australia to help him disappear?

The bottom line is that Fischer stole the equivalent of more than $3 million 2025 Australian dollars from Saddam Hussein’s Baath Party and from Gough Whitlam’s ALP and, perhaps, in the process he used Murdoch as his unwitting accomplice. It is possible, indeed likely, that Rupert’s scoop was a pawn in Fischer’s game.

This essay draws on:

David Greason, ‘Whatever Happened to Henri Fishcer’s Stolen ALP funds?’ Australia/Israel Review 15-28 June 1994

Thomas Kiernan Citizen Murdoch (NY, Dodd, Mead and Company, 1986

Laurie Oakes, Crash Through or Crash. The unmaking of a Prime Minister (Melbourne, Drummond, 1976)

Blanche D’Alpuget, Robert J. Hawke: a Biography (East Melbourne, Schwartz, 1982)

Paul Kelly The Unmaking of Gough (Sydney, Angus and Robertson, 1976)

Graham Richardson, Whatever It Takes (Sydney, Bantam Books, 1994)

Jenny Hocking Gough Whitlam: His Time (Melbourne, Miegunyah Press 2012)

Articles by Phillip Dorling in the Sydney Morning Herald: (19-11-2011; 13-3-2015)

Personal communications from Michael Richardson (1976) and Laurie Oakes (1981)