Southeast Asia pragmatic on China's rise

September 6, 2025

In China this week, the former Australian foreign minister on the global power shifts changing the world, and regional responses.

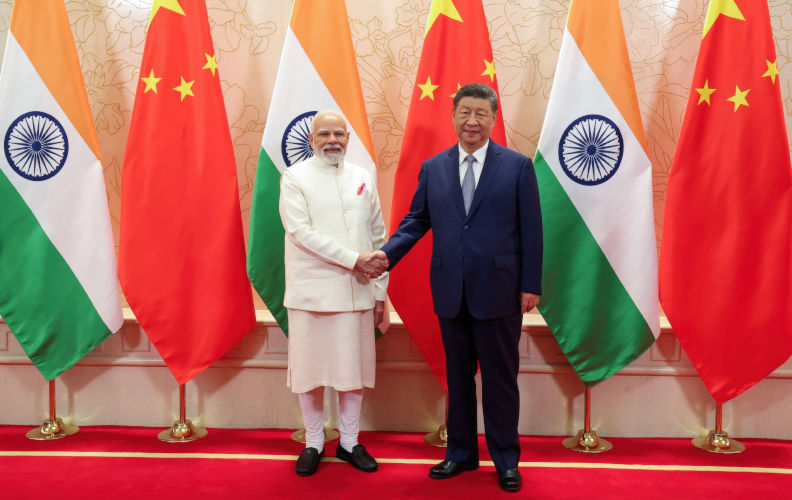

Last week Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping signed a joint communique stating their relationship would not be determined with reference to any third power. For third power, read America. US media noted that 20 years of American cultivation of India under five presidents had been blown apart.

Trump’s 50% tariffs on Indian imports, and a tilt to Pakistan, has roots in his lobbying for the Nobel Peace Prize for which Pakistan has recommended him. This squalid transactional policy-making confirms the dwindling, self-damaging nature of American statecraft, as a president drags the republic toward a post-democratic phase of its history.

Such erraticism will confirm the 10 members of the Association of South East Asian States in their pragmatic approach to China’s rise (the Philippines excepted). Their realism is captured by George Yeo, former foreign minister of Singapore, who says Southeast Asians lived with imperial China for hundreds of years and could deal with the return of a powerful state to their north.

Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto visited China in November a month after his election. In a communique in Beijing he joined Xi in briskly relegating their maritime territorial disputes to a matter of joint development of the disputed area. In January, he enrolled Indonesia as the first Southeast Asian member of BRICS – a prospect that had horrified Canberra when speculated about 10 years back.

I recall as foreign minister sharing the general alarm at such a move by our most important neighbour. Clearly Prabowo is delivering a savvy Javanese judgment on the slide in America’s credibility and the very idea of a unipolar world marshalled from Washington.

Faced with the regional reaction to America’s own behaviour, it almost beggars belief that John Bolton, Donald Trump’s bloodied former national security adviser, thinks two former Australian premiers visiting Beijing, Dan Andrews and myself, makes the remotest difference to the key question here: how Asians themselves are viewing an unpredictable and fissured United States (“ Why are Carr and Andrews legitimising China’s axis of authoritarianism?”).

But this ridiculous misjudgment shouldn’t surprise.

When Bolton was appointed national security adviser in 2018, The Atlantic magazine noted that alone among those who have held this job he had no military experience and no doctoral studies.

The Atlantic said: “He has never studied another region of the world, or another period of history, at the graduate level. He has spent his entire adult life in the interlocking world of hawkish think-tanks, Washington law firms, Republican politics and the right-wing media. And he manifests that narrowness in the smugly insular world view he brings to his new job.”

If he had studied Australia, for example, he might have noted that every opinion poll taken on the subject has shown that Australians do not want to go to war with the US against China – the most recent by 59% to 17%.

And that Chinese-background voters were so alienated by the war talk of Peter Dutton as defence minister and the anti-China diplomacy of Scott Morrison, they handed Labor its lower house majority in the 2022 elections.

He might have learnt that the astonishing early victories of Japan in 1942 briefly persuaded its navy that an invasion of Australia would be possible. But its army had a million men tied down by Chinese resistance and couldn’t spare the divisions. Reason enough for an Australian to join an 80th commemoration of an Allied victory.

That Vladimir Putin would be in Beijing at a celebration of the end of the war is no ground for Bolton’s outrage, given that only last month Putin was accorded a red-carpet welcome by a craven Trump and allowed to strut on US soil as a leader with equal status to his host.

Bolton not only defends the 2003 US invasion of Iraq, but opines that this regime change war should have been pushed over the border into Iran. The American people’s exhaustion with the “endless wars” Bolton championed goes some way to explaining the Trump phenomenon. Today that phenomenon is putting paid to US credibility in Asia.

Republished from Australian Financial Review, Letters to the editor, 2 September 2025

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.