The rise of China and learning the correct lessons from history

September 17, 2025

Given that the only certainty in international affairs these days is uncertainty, we should probably be circumspect about projecting how the world might look decades down the track — let alone how our current moment might be portrayed in the rearview mirror of history.

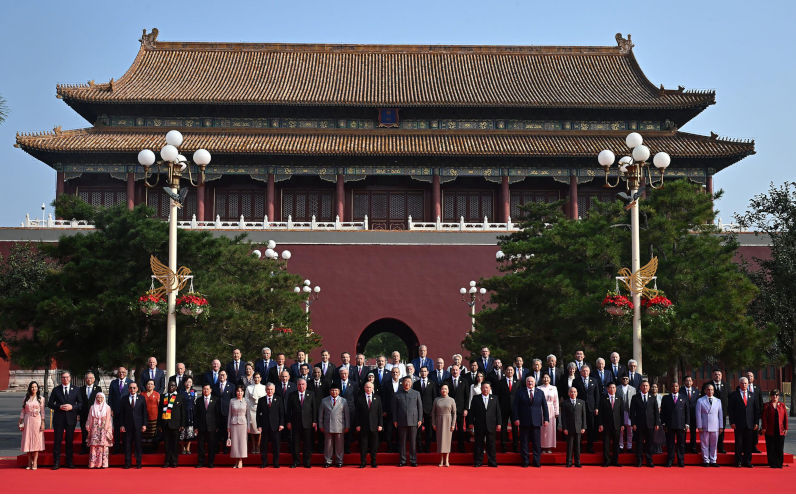

But one does wonder whether the Chinese commemoration in August of the end of World War II in Asia, which brought numerous world leaders to Beijing, might produce some kind of iconic imagery. Years from now, it might grace book covers about the rise of a “post-postwar” global order in the way the famous photos of the leaders at the Yalta Conference or Bretton Woods became emblematic of the roots of the postwar order.

Contest over the politics of historical memory, and its deep intertwining with national identity, is now a part of great power rivalry. Ownership of World War II narratives has become a front in geopolitics, as seen in the frosty reception China’s celebratory parade got both in Japan and in Europe.

Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto was so keen on attending that, even amid a moment of deep political uncertainty during the protests that erupted in late August at home, he made a day trip to Beijing for the event. For Prabowo, the glory might have been worth the pockets of criticism he received from Indonesian social media users for abandoning his post at a moment of political turbulence. In the Chinese press, he was pictured alongside Chinese President Xi Jinping, Russian President Vladimir Putin and others, confirming his status as a leader of consequence.

The Prabowo factor is worth mentioning, for the parade also showed how the distribution of symbolic dignity has become a patronage resource for Beijing. Chinese beneficence has usually been framed in terms of economic benefits, investment, aid and trade. But Beijing has another form of favour it can extend: recognition as a peer in a shared project of building a more equitable distribution of power in the international system, at the expense of Western domination and in favour of the postcolonial world.

Of course, a notionally more democratic distribution of power among states within the international system does not imply more democracy within those states, as vividly evidenced by the prominence of notorious tyrants and kleptocrats among the VIP guests at the Beijing parade. And the superficial symbolism of smaller powers from the Global South being accepted as peers in that shared order-shaping enterprise is exposed whenever China feels it necessary to remind them of their place in the actual pecking order.

As Xiaolin Duan and Lan Tian argue, pondering the way in which historical parallels can lead us down the wrong track if it means embracing “deterministic accounts” of great-power rivalry that assume “that Washington and Beijing are on a collision course”.

“The US-China power transition can be better understood as a course with multiple phases rather than a single match point,” they say. “China has long been in the catching-up stage, but its current trajectory is far from linear. Slowing growth, demographic decline and structural weaknesses raise real doubts about whether Beijing will ever truly surpass Washington.

“This,” they argue, “is not a straightforward power swap.”

On the contrary, they note, “major powers often go to great lengths to avoid direct war. Rising states may delay confrontation to buy time, while incumbents may tolerate challengers to preserve stability. Both sides can accommodate, balance through allies or redirect pressure onto third parties.”

The implication is that a dysfunctional US-China relationship is one born not of structural inevitability or security necessity, but of the contingencies of political choices made on both sides of the Pacific. And it is in no way to excuse the solipsistic and irresponsible features of Chinese policy to note that it is primarily the ideologically-driven panic in Washington that has been the decisive factor in diverting the region from what might otherwise have been a manageable shift in strategic power.

The current American approach will result in a future in which US political influence in Asia and the Pacific is much weaker than it would have been had it followed one more attuned to the needs and preferences of regional countries deeply enmeshed with China economically and exposed to the risks of US-China conflict.

It is not just the choices of the great powers that matter. The regional majority has the opportunity and responsibility to take the lead in designing an order that protects its interests – one in which China can be engaged multilaterally on areas of both mutual and conflicting concern, in ways that aggregate the voices of small and middle powers.

This is why structures like RCEP, CPTPP and other ASEAN-based frameworks matter. For Southeast Asia, investing in these processes is the best insurance policy – imperfect and incremental, but still the surest way to ensure that regional order is not left entirely to the designs of great powers.

Republished from East Asia Forum, 15 September 2025

Pearls And Irritations recommends: Australia needs to diplomatically disengage from our 'dangerous ally'

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.