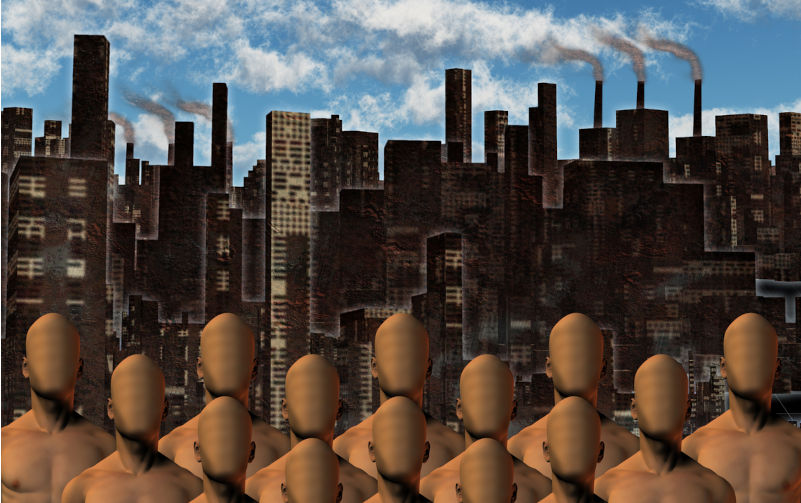

The social smog of neoliberalism: How competition breeds violence and division

September 15, 2025

The Industrial Revolution transformed the material basis of human life. By harnessing energy and perfecting machines, engineers satisfied physical needs on a mass scale.

Rational efficiency was their guiding principle: stronger engines, faster production, greater output. Yet in this pursuit of efficiency, they ignored the hidden costs. Industrial processes produced pollution, waste that accumulated invisibly for decades before its delayed impact became undeniable. The smoke and smog of industry, once dismissed as inevitable, eventually poisoned air, water and climate.

Neoliberalism represents a similar revolution in the social sphere. Economists and managers recast themselves as social engineers, promising that competition would unleash efficiency, innovation and prosperity for all. But competition never crowns everyone. It produces winners who rise with rewards, and losers who are cast aside. Just as industrialists ignored the smoke and sludge their machines spewed into the environment, neoliberals ignored the human wreckage their creed produced, communities stripped of dignity, children burdened with shame, whole groups condemned to permanent disadvantage. The glittering success of the few is built on the exclusion of the many.

This waste is not material, but human. It is the rejection, exclusion and shame imposed on those who are cast as losers in competitive systems. For decades, this “social pollution” was denied or minimised. But like the carbon emissions of the industrial era, its consequences were delayed rather than absent. Today they have arrived with force: rising social violence, extremist movements, fractured communities and disenchanted youth.

Neoliberalism promised efficiency and prosperity. What it delivered is a social climate crisis, a choking smog of exclusion that corrodes belonging and fuels violence.

Neoliberalism is more than an economic framework; it is a worldview. Drawing on the work of Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman, it elevates competition as the ultimate principle of social organisation:

- Competition as virtue. Winners are portrayed as efficient, talented and deserving; losers are dismissed as lazy, unworthy or defective.

- Marketisation of society. Public services, education, healthcare, welfare and aged care were restructured to mimic markets. Choice replaced universality; accountability replaced trust; measurement replaced meaning.

The ideological flaw is simple: in markets, losers can be firms that fail. In human services, losers are people, children, families, patients, the elderly. A philosophy that insists on producing losers therefore manufactures systemic exclusion.

Like industrial pollution, the waste of neoliberalism was not immediately visible. For a time, the promise of growth and prosperity masked the damage. But the social waste has now accumulated beyond denial.

- Inequality – Wealth has concentrated in a small elite, while opportunities for the majority have narrowed.

- Disenchantment – Communities hollowed out by job loss, poverty, and underfunded services experience a pervasive sense of abandonment.

- Polarisation – The competitive creed fractures society into winners and losers, generating resentment and hostility across class, race and identity lines.

This is the social pollution of competition: exclusion that accumulates in the emotional and neurological lives of citizens. It is not seen in smokestacks, but in violence on the streets, in extremist movements, in the despair of disenchanted youth.

To understand why this pollution is so toxic, we must turn to neuroscience. Human beings are not rational calculators, but social organisms. The brain evolved to achieve homeostasis, not only of the body, but of the social self.

- Exclusion as pain – Studies show that social rejection activates the same brain regions as physical pain, especially the anterior cingulate cortex and insula.

- Toxic stress – Chronic exclusion triggers the stress response (HPA axis) repeatedly, flooding the brain with cortisol and impairing attention, memory and regulation.

- Toxic shame – Over time, exclusion is internalised. The message shifts from “I did badly” to “I am bad”. This shame becomes embedded in neural pathways, resistant to logic or reassurance.

The human brain demands belonging. Neoliberal systems deny it to many. The result is not just economic inequality, but neurological injury: a wounded social brain primed for anger, despair and alienation.

Exclusion does not sit passively within young people. It demands action, a search for belonging. Here the outcomes diverge.

- Violent extremism. Particularly among boys, shame often converts to rage. Far-right groups offer a tribal identity: “you are not a loser, you are a warrior”. Violence becomes a ritual of belonging. The recent surge in teenage stabbings mirrors this dynamic, where aggression is reframed as strength and exclusion is channelled into brutality.

- Older criminal networks exploit the same vulnerabilities, recruiting disenchanted youth into violence for profit.

- Activist solidarity. Others channel exclusion into collective protest. Aboriginal-led movements exemplify this path, transforming historical rejection into demands for justice and recognition. The same wound of exclusion can fuel campaigns for fairness and inclusion.

The difference is not in the pain, but in the pathways available. One leads to destructive violence, the other to constructive activism. The decisive factor is whether society provides inclusive communities where belonging can be restored.

The tragedy is that institutions most capable of restoring belonging, particularly through education, have themselves been captured by neoliberal logic.

- Functional stupidity – Alvesson and Spicer in their book Stupidity Paradox describe how organisations suppress deep reflection in favour of compliance.

- The bureaucratic hive – Bureaucracies behave like organisms bent on self-preservation. Ministers are shielded from uncomfortable truths; policy serves the system’s image rather than society’s needs.

- Reproduction of exclusion – Funding inequities, high-stakes testing and punitive behaviour policies deepen, rather than heal, wounds, reinforcing the cycle of rejection.

This management hoax disguises failure as reform. It preserves the competitive creed while leaving the social pollution untouched.

Yet there remains hope. Public schools, flawed as they are, remain the only universal institutions that reach every child. They are crossroads: they can either reproduce exclusion or act as the great counterforce.

When schools are captured by competition, a destructive cycle unfolds. Competitive, private schooling breeds inequality. Inequality hardens into exclusion. Exclusion corrodes the sense of self and produces shame. Shame curdles into extremism and violence. Violence spreads fear. Fear, in turn, drives an even greater appetite for competition, and the cycle tightens, generation after generation.

But society could choose a different path, one that begins by organising schools around equity, inclusion, safety and belonging. Belonging restores the brain’s equilibrium, healing the fractures of rejection. From that stability grows empathy and reflective reason.

Schools cannot erase inequality, but they can buffer its blows. By meeting the brain’s deepest need for belonging, they can transform rejection into resilience and despair into solidarity. In doing so, they stand as our last line of defence against the unravelling of society.

The Industrial Revolution taught us that efficiency without regard for waste leads to environmental catastrophe. Neoliberalism has repeated the error on the social plane. By insisting on competition, it has generated a hidden pollution: the exclusion, shame and rejection of millions.

We are now breathing that social smog. Teenage stabbings, racist rallies, extremist movements – these are not random outbreaks, but the delayed consequences of neoliberal waste. They are the predictable outcomes of systems that manufacture losers and deny belonging.

The way forward is clear. Just as societies learned to regulate pollution and invest in sustainability, we must confront neoliberalism’s social waste. And the most immediate arena for action is education. If schools remain competitive marketplaces, they will keep producing the excluded. If they are reclaimed as fair, inclusive commons, they can restore the balance of the social brain and anchor democracy itself.

The choice is stark: allow the smog of exclusion to thicken until violence overwhelms us, or build schools that clear the air with fairness, belonging and hope.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.