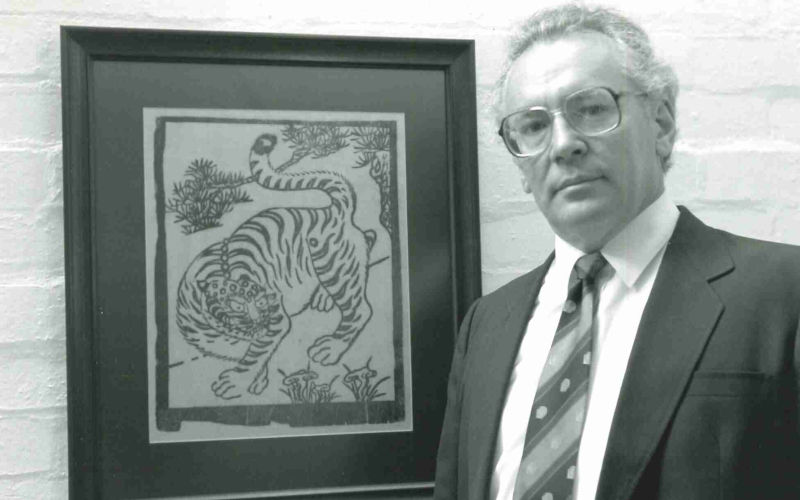

Vale Adrian Buzo (1948–2025)

September 10, 2025

In August 2025, the historian, diplomat, linguist, and Korean Studies pioneer, Dr Adrian Buzo passed away after a long battle with illness.

Known for intellectual curiosity, warmth and generosity, Adrian Buzo helped lay the foundations for Korean Studies in Australia and advanced international understanding of the Korean Peninsula – particularly the origins of the political culture of North Korea. He also had a unique talent for jazz piano, a love for all forms of literature (George Eliot was a particular favourite) and, arguably, a not-so-typical traditional Korean trait: a deep love of cats.

Adrian Buzo was born in 1948 in Brisbane, the son of Zihni Jusuf Buzo OAM from Berat, Albania, a Harvard University graduate and civil engineer, and Elaine Johnson, an Australian schoolteacher of Irish descent. After some years residing on Sydney’s Middle Harbour, at the age of seven Buzo and his family moved north to Armidale, where his father worked a civil engineer and assumed a position at the University of New England. There, the young Buzo and his brother Alex attended the Armidale School. His father later was employed in Switzerland and Buzo attended the International School of Geneva and then finished his schooling at North Sydney Boys High School.

In 1973, Adrian graduated with honours in Japanese at the University of Sydney, and soon after joined the Department of Foreign Affairs. He served two years in the Australian embassy in Seoul where he undertook Korean language studies at Yonsei University. In April 1975, Adrian was part of a group of three diplomats sent to Pyongyang to open Australia’s (first and so far only embassy) to North Korea, where he was to serve as Second Secretary. Sadly, the North Korean Government declared them personae non grata and they were forced to close the embassy and leave the country, making those few months the entire lifespan of Australian diplomatic representation in North Korea.

Over the next few years, Adrian became an academic commuter between Sydney and Seoul, graduating in 1981 with a Master’s degree specialising in the study of early Korean writing systems from the Department of Korean Language and Literature at Dankook University, Seoul. In 1997, he was awarded a doctorate in Asian Studies from Monash University, where he became a senior lecturer in Korean Studies.

In 1992, Adrian was appointed to Australia’s first full-time Korean Studies position as director of the National Korean Studies Centre, one of four Asian Studies centres funded as part of the Australian Government’s implementation of the 1987 National Policy on Languages to promote the teaching of Chinese, Japanese, Indonesian and Korean. The NKSC was based at Swinburne University of Technology and was instrumental in establishing Korean language programs across the country, in particular at Swinburne, Monash University and the University of Melbourne. The NKSC was also heavily involved in supporting the establishment of Korean as a subject at Griffith University, UNSW and the University of Queensland. Further, the NKSC supported teaching Korean in primary and secondary schools such as Strathcona Girls Grammar in Melbourne. The NKSC facilitated the establishment of a Korean language resource collection and the appointment of a Korean librarian at Monash University and ran student exchange programs, hosted Korean scholars, and developed Korean language-teaching materials.

All of the Korean language programs in Melbourne relied on one of the few and, to this day, one of the best, Korean language textbooks Learning Korean: New Directions (Gi-Hyun Shin and Adrian Buzo, NKSC, 1994). Later, this was supplemented by the book and cassette tape set Korean through Active Listening, one of the first texts to focus on listening comprehension, created with thanks to Adrian Buzo by a grant from the NKSC.

After the closure of the NKSC in 1999, Adrian went on to hold posts at Macquarie and UNSW. At Macquarie, he helped build the Korea University-Macquarie jointly delivered Master of Translating and Interpreting Studies.

Adrian served on numerous government and scholarly boards. He was an inaugural board member of the Australia Korea Foundation (1990–2000), chair of the National Accreditation Authority for Translators and Interpreters Korean panel (1982–2007), and in the 2010s an advisory member of the Sydney-based Korean Cultural Centre. He was an active member of the Korean Studies Association of Australasia, the Asian Studies Association of Australia, and the Royal Asiatic Society, Korea Branch, where he served as a council member from 1980 to 1981.

Adrian published widely in the field of Korean language and studies and, having a deep love and knowledge of Korean literature, one of his favourites was the poetry of Kyunyo-jonn. For instance, he published an annotated translation (with Tony Prince) of Kyunyo-jonn: The Life, Times, and Songs of a Tenth-Century Korean Monk (Literature Translation Institute of Korea, 1993) which offers a detailed picture of the norms and practices of Korean Buddhism in a period when Buddhism was the prevailing ethical force in society.

But Adrian is best known for his insights and his written work on North Korea. He authored critically acclaimed books on the politics and leadership in North Korea, such as his books The Making of Modern Korea (Routledge, 4th edn, 2022) and The Guerilla Dynasty: Politics and Leadership in North Korea (I.B. Taurus, 1999) and a chapter in the Routledge Handbook of Modern Korean History (Ed., Michael Seth, 2016). Of these, The Guerrilla Dynasty is his most well-known work. Originally the topic of Adrian’s doctoral thesis, the book is now in its second edition (Routledge, 2018), remaining a key text for understanding the inner workings of North Korea’s political elite.

Until the 1990s, global interest in North Korea was primarily focused on the international relations concerns of security and conflict. The country also struggled (and still does) with an acute lack of primary sources. As Adrian noted in the introduction to his edited volume, the Routledge Handbook of Contemporary North Korea (2020), when he searched for nuggets of useful information in the early days of his research, he had to wade through reams of the “baleful twins” of misinformation or disinformation. He did this at a time where most contemporary analysis was dominated by the topics of power, hegemony, conflict, weapons development, global security and the economy.

In the same introductory essay, Adrian noted that a new wave of North Korean scholarship, informed by greater access to defector testimonies had somewhat improved the situation, although the legacy of North Korea’s political origins is still often positioned as marginal by the “mainstream”:

“We have moved on quite a ways from the days when former US vice-president Walter Mondale could feel moved to assert that ‘Anyone who tells you that they are an expert on North Korea is either a liar or a fool’, though not so far as to give the lie to Brian Myers’ recent observation that we always know we’re at a North Korea conference because we can’t tell the political scientists from the international relations people.”

Adrian transcended generalisations and Cold War ideological boundaries to place North Korea in its unique historical context. His approach was informed by a detailed knowledge of Korean history, first-hand experience in North Korea and a meticulous commitment to primary research. He drew on an impressive number of sources, as Charles Armstrong observed in a review of The Guerilla Dynasty: Adrian “read more issues of People’s Korea, the pro-DPRK periodical published in Japan, than anyone should be required to read in a lifetime”. The resulting research challenged established narratives with new evidence and perspectives on North Korea.

Buzo argues that the origins of North Korea’s still-vibrant culture of profound nationalism and militarism, with its insular, paranoid and self-reliant characteristics, is largely a variation of Stalinism filtered through the experience of Manchurian guerrilla warfare, shaped above all by the idiosyncratic world view of Kim Il Sung (1912-94). As Adrian notes in the updated version of The Guerilla Dynasty, “in a state governed by personal autocracy, the significance of the character, personality and life experiences of the leader is self-evident”. It is hard to argue against this case in North Korea.

Kim’s experience in his formative years as an anti-Japanese fighter in a mobile guerrilla unit in the harsh climate and remote areas of Manchuria during the 1920s and 1930s definitively shaped North Korea’s ongoing mode of political operation. In the Routledge version of The Guerilla Dynasty he puts it: “few individuals have shaped the character and destiny of a state in the modern world as thoroughly as he has, to the extent that the past history and present condition of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea cannot be understood apart from his life and career”.

As such, Adrian argues that the emergence of this Guerrilla dynasty represents a fundamental break with Korea’s political traditions, and he is highly critical of scholars who find elements of Choson dynasty practices in contemporary North Korean politics. This is a significant contribution although somewhat downplayed by Adrian himself. He described it in the 2018 update as more a failure of many to accept this as a matter of “common sense”:

“That Kim Il Sung’s guerrilla experience and the DPRK’s extended Stalinist tutelage have definitively shaped the nation remains not so much an argument but a common-sense and recurring theme, and it should become clear to the reader that I find reports of the death of Stalinism in the DPRK greatly exaggerated, for how one can say this with the country’s personality cult politics, the fundamental structure of its governmental institutions, its gulags, and its state terror apparatus still thriving, and with the much-vaunted market economy serving the Kimist state much as Lenin’s New Economic Policy served the Leninist state, continues to defeat me.”

Much like his jazz playing, Adrian embraced syncopation. By that I mean Adrian marched to the beat of his own drum. He did not “play the game”. In the academic context, he was not incentivised by universities’ fixation with ranking systems driven by metrics – the number of publications, citations creating one’s “impact” factor. In the corporatised university context, he did not substantially reinvent himself to survive the universities’ ever expanding restructuring project that invariably targets Area Studies and language programs. In the North Korean Studies context, where the country receives a disproportionately large amount of media attention, he did not chase media exposure or flood social media.

Adrian was not to be distracted from what he considered really matters. He continued down the road less travelled, the path of slow scholarship, of time-consuming and meticulous research that informed thoughtful, reflective, insightful, original, explanatory and comprehensive tomes. The fact that this path is often unrewarded, and often seen by neoliberal universities as too costly, made navigating the “system” often problematic and at times left Adrian puzzled, despondent and disillusioned. But while Adrian’s “success” eludes capture in such academic metrics, we can understand that his success lies in a small but mighty legacy – playing the leading role in establishing the field of Korean Studies in Australia and that his research continues to have an outsized influence on an entire generation of students of North Korea. Maybe Adrian’s life and work can remind us about what really matters, about why we joined the academy in the first place.

To end with a quote from one of Adrian’s favourite books and a message for “old school” scholars everywhere:

“For the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.”

Mary Ann Evans (George Eliot), 1871; Middlemarch, ending passage.

Republished from Asian Studies Association Australia, 5 September 2025

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.