What goes around, comes around

September 3, 2025

With Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi attending the SCO (Shanghai Co-operation Organisation) meeting in China this week, we may be witnessing a tectonic shift in international relations, one which could undermine the basis of Australia’s relations with Asia.

Apart from anything else, how is Canberra’s much-favoured QUAD (Japan, India, Australia, the US) supposed to co-exist with strongly pro China-Russian oriented SCO?

India joined the SCO early, in 2015. But border clashes between Chinese and Indian troops — the worst being in the freezing Himalayan Galwan Valley in 2020, with 20 Indian dead — had kept the two countries firmly apart.

Recent years saw some renewal of relations. But that was unable to compete with the “bromance” with the US, which saw India strongly favoured in US relations. That is, until Trump’s 50% tariffs arrived and, in mediating an India-Pakistan conflict, Trump seemed to favour the Pakistani side.

The tariffs were bad enough but what really upset New Delhi was the way its complaints over the tariffs were met by a barrage of depreciating and insulting remarks from Trump and his notorious trade adviser, Peter Navarro – remarks immediately seen by the sensitive Indians as colonial-minded arrogance.

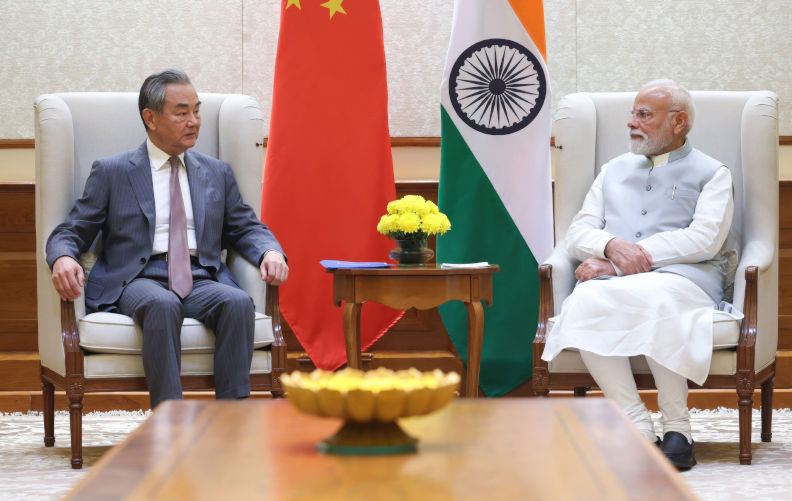

Meanwhile, some smooth talk by China’s visiting Foreign Minister Wang Yi seemed to ease frontier worries and, combined with Russia’s promises to ignore US threats over continuing oil supplies, seemed to improve relations enough to create a shift in alignments to the point where I-C-R (India, China, Russia) was being suggested as the new foreign policy acronym.

But will that come to pass?

Many still believe the frontier problem will continue to keep India and China apart. I am less pessimistic and for one good reason – as a junior diplomat on the China desk in Canberra in 1962 I was closely involved in studying the first Sino-Indian border clash, at Thagla Ridge in the eastern Himalayas. We had the maps proving China was in the right. But when the 1962 war broke out, our superiors decided it was in our interest to let the Indians continue to believe they were the right, and the myth has continued ever since.

Finally, some unbiased Indian observers have begun to agree the early frontier disputes were the result of India’s (Nehru’s) forward policy along the frontier. Nehru’s upset over China’s occupation of Tibet had eventually led to a war that has poisoned relations for the next 60 years.

But today, as borders open and direct flights resume, it has become hard for India to maintain the initial angst. I-C-R could well be the new reality.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.