When Australia defied US nuclear plans. Part 1: B-52s over Australia in the 1980s

September 6, 2025

It wasn’t always like this. For a brief moment Australia stood apart.

Liberal Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser compelled Washington, much to its chagrin, to publicly confirm that its nuclear-capable B-52 bombers then regularly exercising in Australia were not carrying nuclear weapons.

Fraser’s success was more than a diplomatic anomaly. It was a deliberate assertion of Australian sovereignty against Cold War orthodoxy – a rare instance of a U.S. ally bending the rules of nuclear engagement to serve its own democratic and strategic imperatives.

‘ NO B52s’, Instagram.

Late in the afternoon of Wednesday, 11 March 1981, prime minister Malcolm Fraser rose in the House of Representatives to deliver a major statement on defence policy that would redefine Australia’s alliance with the US and break with one of Washington’s most sacred nuclear doctrines.

A year earlier, just weeks after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, Fraser’s Liberal-National Country Party coalition had announced US Air Force B-52 operations over northern Queensland. Codenamed BUSY BOOMERANG, these missions involved hazardous, low-level terrain avoidance exercises designed to prepare bomber crews for potential nuclear strikes.

In his 11 March 1981 Ministerial Statement, Fraser clarified the final terms of the terrain avoidance exercises – and revealed a second, more strategically significant mission. Under the codename GLAD CUSTOMER, B-52s would not just overfly Australia, they would stage through RAAF Darwin to conduct maritime surveillance operations over the Indian Ocean.

Regularly hosting US forces in this way marked a significant break from past defence policy and alliance co-operation arrangements, prompting internal deliberations about how much control Australia could retain over its international involvements.

These concerns, however, did not prevent the missions from going ahead. Both would run for more than a decade, continuing into the Hawke Labor years, and set in motion what is now approaching half a century of near-continuous Australian involvement in US strategic bomber operations.

But it wasn’t the start of B-52 staging operations in Australia, or the mission profiles, that stunned the chamber. It was Fraser’s declaration that the bombers would be “unarmed and carry no bombs”, meaning no nuclear weapons.

The Labor opposition was incredulous. Shadow foreign minister Lionel Bowen dismissed the claim outright:

“Last year the Americans apparently indicated to this government that they would inform it in advance whether any of its B-52s were carrying nuclear weapons. This was a mistake…They will not do it.”

Bowen had good reason to be sceptical. Fraser’s declaration was a direct repudiation of Washington’s global policy to neither confirm nor deny the presence of nuclear weapons on its aircraft, ships or submarines – a doctrine enforced with near-religious zeal since the 1950s.

But Bowen was wrong. Fraser had indeed secured an exemption to America’s NCND policy, and Washington publicly confirmed it two weeks later – a diplomatic first, never repeated by any other nation.

While other US allies have proclaimed nuclear-free policies, all have, in practice, tolerated visits by American nuclear-armed vessels or aircraft. The lone exception is New Zealand, which since 1984 has enforced its nuclear ban by refusing entry to vessels it deems armed with nuclear weapons – a move that led to its suspension from the ANZUS Treaty, a status that remains unchanged today.

Fraser’s achievement was unique: he compelled Washington, much to its chagrin, to publicly confirm that its nuclear-capable B-52 bombers operating in Australia were not carrying nuclear weapons.

His success was more than a diplomatic anomaly. It was a deliberate assertion of Australian sovereignty against Cold War orthodoxy – a rare instance of a US ally bending the rules of nuclear engagement to serve its own democratic and strategic imperatives.

And yet, despite its significance, Fraser’s nuclear heterodoxy has been buried under decades of alliance conformity, classified military archives, and strategic amnesia.

This is the story of the brief moment when Australia stood apart – and a reminder that such choices are possible. Today, as the United States rotates not just strategic bombers but the full spectrum of air force, army, navy and marine forces through Australian bases, questions of national independence are resurfacing amid escalating risks of being drawn into international conflicts – including nuclear war.

Rehearsing nuclear war

The origins of the 1980s B-52 deployments lie not in Australia, but in the skies over Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War and, later, in the geopolitical shock of the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

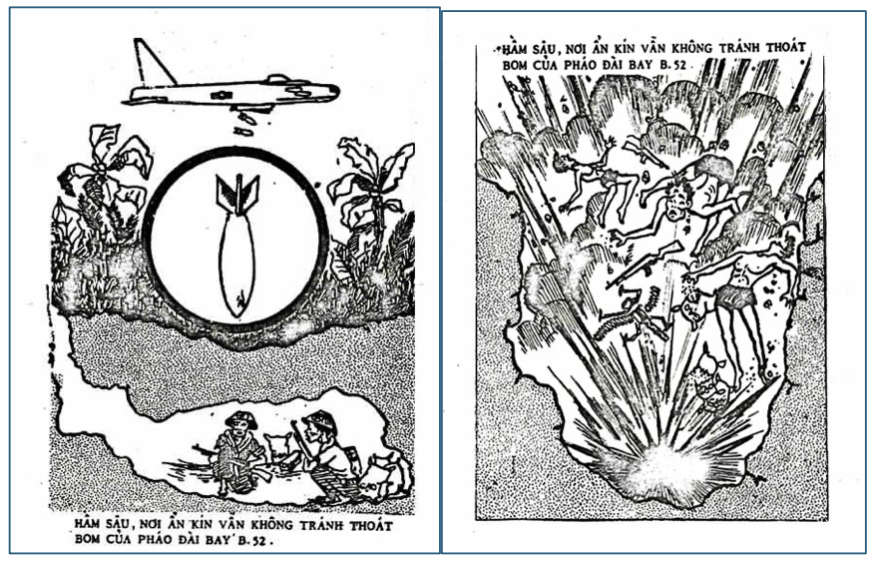

The B-52 Stratofortress bomber — designed primarily as a nuclear strike platform — was adapted during the Vietnam War to carry out high-altitude “area saturation” bombing. Over the course of the war, more than two million tons of bombs were dropped on the three countries of Indochina in a deliberate campaign of terror that was as psychologically devastating as it was physically destructive.

This new and prolonged conventional role over Indochina eroded the nuclear readiness of the B-52 fleet. After seven years of unleashing devastation from high above, US Strategic Air Command was determined to restore the skill level required to execute its core nuclear warfighting mission: low-level offensive strategic penetration over hostile terrain.

SAC urgently sought suitable training locations. Existing routes over South Korea were limited in range, and negotiations for additional corridors in Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, and Japan had stalled.

Australia, offering long, uninterrupted corridors and a favourable political environment, was the ideal choice. The Fraser Government acted swiftly, granting approval in October 1979, with flights beginning the following February.

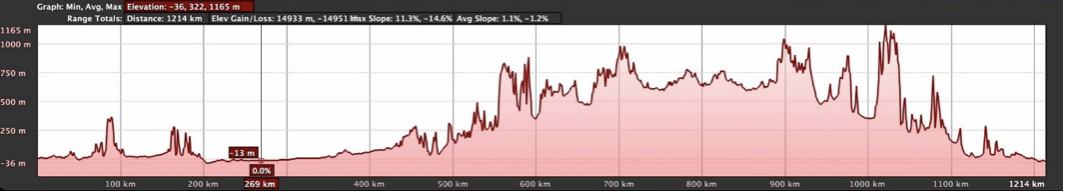

The initial BUSY BOOMERANG flights covered two northern Queensland routes, stretching nearly 900 and 1200 kilometres respectively. By October 1982, the program expanded to six routes across Queensland, Western Australia, and the Northern Territory, under the codename BUSY BOOMERANG DELTA.

Routes and elevation profiles of first USAF B-52 terrain avoidance training overflights over north Queensland, March 1980. Route 1 – Mount Adolphus Island – Coen – Racecourse Mountain – Princess Charlotte Bay (892 kms). Route 2 – Shelburne Bay – west of Cooktown – Walters Plains Lake – west of Cooktown – Lookout Point (c. 1214 kms). Source: Google Earth; and Department of Defence, ‘US Air Force B-52 Flights’, Defence Media Release, 18 Feb 1980.

In the first year of operations, 23 missions were flown. By 1984 that number had surged to 94. Each flight was extraordinarily demanding, requiring crews to hug mountainous terrain at 100-150 metres above the ground at speeds of up to 600-740 kph, navigating by visual- and instruments-only methods, including at night.

What Australia officially described as “low-level navigation training” was, in reality, high-risk rehearsals for nuclear strike missions – carried out to meet the requirements of SAC’s all-encompassing Single Integrated Operational Plan for nuclear war with the Soviet Union and China.

Controlling the seas

If BUSY BOOMERANG was about nuclear readiness, GLAD CUSTOMER was about controlling the seas.

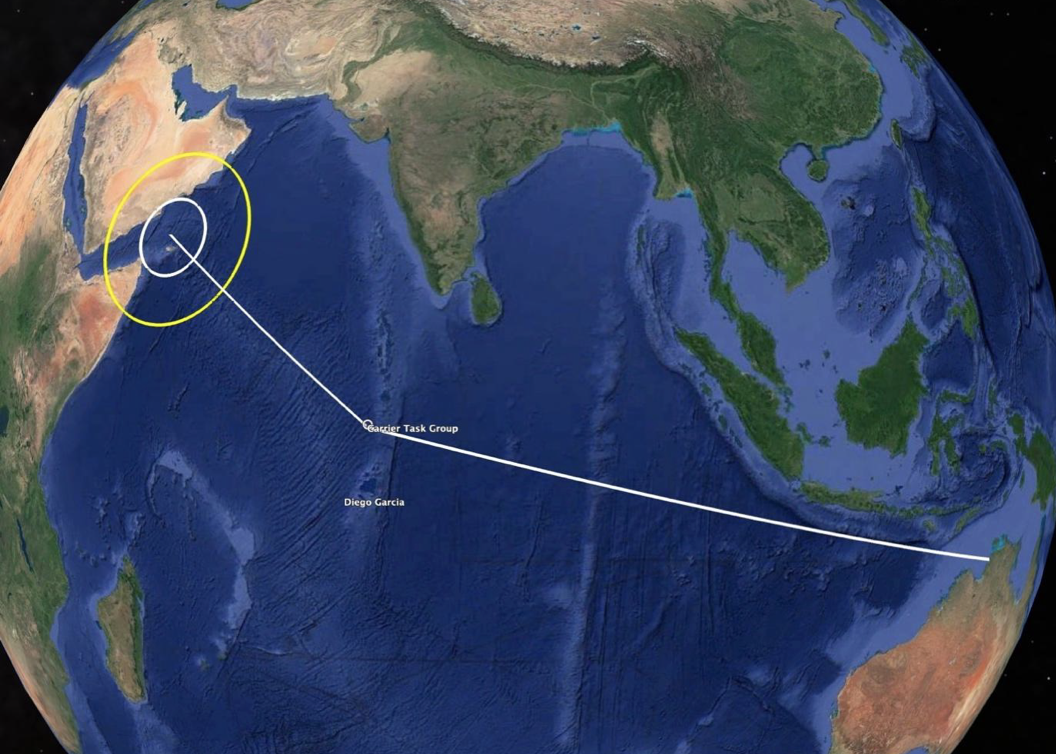

The Indian Ocean maritime surveillance mission staging through Darwin originated in wider US plans to counter Soviet regional expansion and possible threats to Western control over Middle Eastern oil sources in the aftermath of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

The B-52’s extraordinary range and versatility made it an attractive complement to the P-3 Orion maritime surveillance aircraft, particularly after regional political shifts, such as the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran, constrained basing options for P-3 Orions.

Australia’s reliability, permissiveness and geographic positioning gave it disproportionate strategic importance in enabling the US to project strategic air power and conduct maritime surveillance across the Indian Ocean.

The first GLAD CUSTOMER missions involved three B-52 bombers accompanied by six KC-135 refuelling tankers and about 100 US Air Force personnel to support the operations. Departing from bases in the continental United States, the aircraft staged through Guam before continuing to Darwin, where they prepared for a gruelling 26-hour operation over the Indian Ocean. From there, the bombers flew west into the Indian Ocean, north past Diego Garcia to rendezvous with a carrier task group, and onward to the waters off Yemen.

GLAD CUSTOMER was, in fact, a derivative of a broader and more ambitious campaign launched by Pacific Command in the mid-1970s — BUSY OBSERVER — involving a series of maritime surveillance, interception, and minelaying operations in co-operation with US Seventh Fleet carrier battle groups. Over time, BUSY OBSERVER evolved into a mission set that included armed interdiction of Soviet naval power.

Seen in this wider context, GLAD CUSTOMER was, from Washington’s perspective, far more strategically significant than the term ‘maritime surveillance’ implied.

[This article draws on Vince Scappatura and Richard Tanter, B-52 strategic bombers in Australia 1979 – 1991 and the nuclear heterodoxy of Malcolm Fraser, Nautilus Institute Special Report, 4 August 2025. It follows the authors’ Nuclear-capable B-52H Stratofortress strategic bombers: a visual guide to identification, Nautilus Institute Special Report, 26 August 2024. To come: Vince Scappatura and Richard Tanter, ‘When Australia Defied U.S. Nuclear Plans: Part 2. Sovereignty at stake’.]

Republished from Declassified Australia, 26 August 2025

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.