Almost no Australians study Chinese any more. That’s a problem

October 11, 2025

Fewer than five Australians per year are graduating from honours programs in Chinese studies with language, raising fears the nation is losing the expertise needed to navigate its most complex foreign relationship.

The House of Representatives’ education committee last month launched a review into the education system’s engagement with Asia following a multi-year decline in the number of Australians learning Asian languages.

Education experts are concerned the decline in Australians studying Chinese could threaten the country’s sovereign knowledge of China at a time it is becoming more important for the economy and foreign policy.

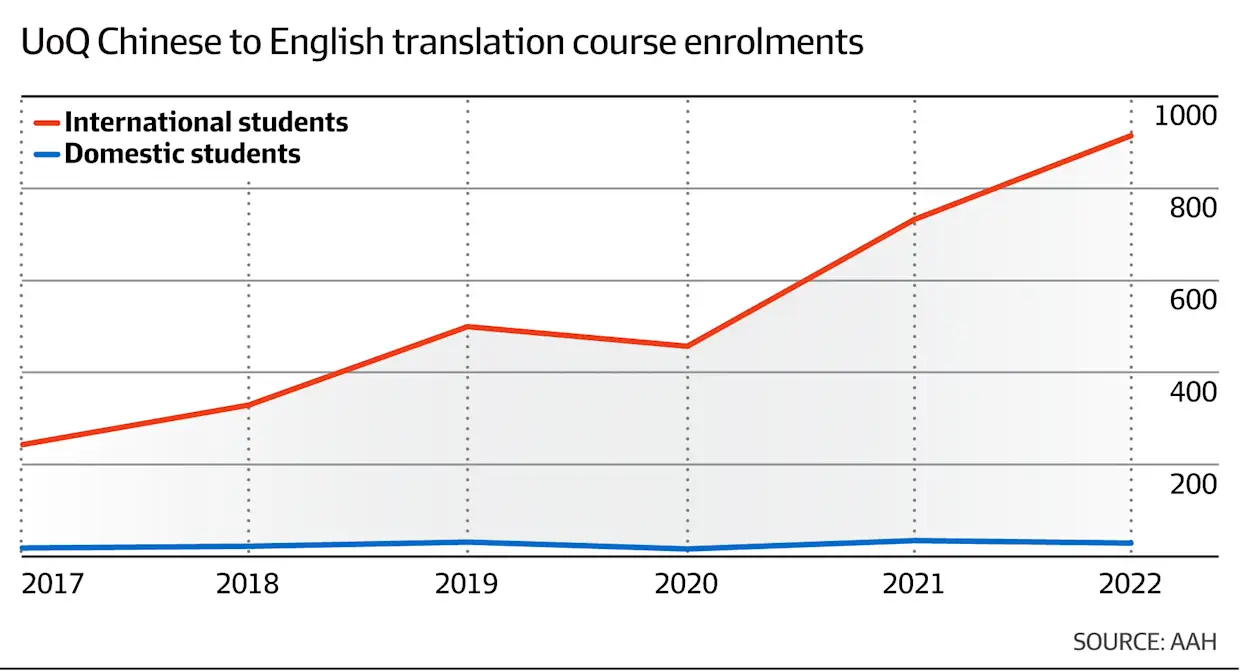

The committee’s inquiry follows a 2023 report which found that fewer universities were offering advanced Chinese studies, while language courses were increasingly dominated by international students.

Experts are particularly worried about the decline in universities offering fourth-year honours programs in Chinese – a key source, historically, of locally generated China knowledge and advanced language skills.

Between 2017 and 2021, it found only 17 Australians completed an honours program in Chinese studies with language – no more than five per year on average. Only seven universities of the 14 consulted offered an honours program in Chinese studies with language.

Joe Lo Bianco, a University of Melbourne professor who chaired the advisory group that wrote the report, said trends it identified had probably not reversed since its publication.

“Honours degrees and senior degree courses are the point at which students go for some kind of specialised comprehension of an aspect of China, that would commit them to be interested in the place and devoted to it for extended periods of time,” Lo Bianco said.

“The critical degrees that we need to keep students active and interested in particular countries of strategic importance to Australia are being lost.”

Anne McLaren, honorary professorial fellow at the University of Melbourne’s Asia Institute, said numbers of participants in Chinese honours programs had always been small, but had dwindled further over the past two decades.

“The situation is such that these programs are hardly viable and may be difficult to retain into the future,” McLaren said.

“Gaps in China capability jeopardise Australia’s ability to promote its national interests … It also undermines the nation’s ability to solve complex problems with Australia’s interests front of mind.”

The report also found that advanced Chinese language courses were increasingly dominated by international students.

Of the 30 to 40 people at the Australian National University studying English to Chinese translation or interpretation per year, just five to eight were domestic students.

It also found that more universities were closing China-specific courses and replacing them with more generalist classes on international relations and geopolitics.

McLaren said the large number of Chinese-background students in university classes could be challenging for Australian students with no background.

“University teachers in Chinese language programs have their hands full teaching the large numbers of international students (mostly from China) and catering to their very different needs,” McLaren said.

“Many of these students enrol in advanced translation classes that are mostly unsuitable for those with limited language background.”

Lo Bianco said foreign students enrolled in Chinese language courses were often Japanese or Korean, and that they often had advantages over Australian-born students. Traditional Japanese Kanji characters share similarities to Chinese characters.

“I’ve got no problem with anyone enrolling in it. But it does have a consequence for Australian-born students whose presence in these programs needs to be facilitated,” Lo Bianco said. “Not just their participation, but their success. And their success has to be through targeted programs.”

While there are a million Mandarin and Cantonese speakers in Australian households, those skills do not automatically translate into capability, he added.

Often people who speak Cantonese or Mandarin at home may be unfamiliar with the written form. People who speak Cantonese at home have to learn a new spoken form of Chinese if they enrol in a Mandarin course, Lo Bianco said.

“Chinese is learnt by students who are very proficient and literate in the language, and students who are absolute raw beginners. These two cohorts couldn’t be more different from each other in their needs,” he said.

With the US stepping back from multilateral organisations under US President Donald Trump, Lo Bianco said the world looked less multipolar and more China-directed.

“We have to know this society, which is the world’s driving economy, much better than we do,” he added.

Daniel Kane, formerly the head of Chinese studies at Macquarie University, estimated in 2019 that there were only 130 Australians with no Chinese background who could speak Mandarin fluently.

Republished from Australian Financial Review, 7 October 2025

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.