Australia's decolonisation runs aground

October 1, 2025

When asked last week whether his government was still intending to reach for the goal of an Australian republic Prime Minister Albanese declared that he would not be progressing the cause while he was in office.

It was a clear reversal of what had been promised when the government came to power in May 2022. He advanced two arguments in explanation. He reached back 25 years to the failure of the 1999 Republic referendum, explaining that the Australian public had made their views clear then. With somewhat greater cogency he intimated that the defeat of the Voice referendum in October 2023 had destroyed his appetite for significant constitutional change.

One can have some sympathy for this reaction. But the twin failures of Indigenous reconciliation, and the generation-long hope for an Australian head of state, provide vivid illumination of the country’s inability to make a decisive break with our colonial heritage. This matters in ways that are not immediately apparent to the domestic audience. It determines the way Australia is seen by observers in many parts of the world. It is an enduring liability.

The interest shown by international commentators in the Voice referendum was not widely appreciated domestically. The defeat was reported in Europe, the Pacific, North America and Asia. What was even more notable was the unanimity of the commentary. The common view was that Australia’s Indigenous community had been rebuffed and that Australians had turned their back on a creative offer of reconciliation.

The Uluru Statement from the Heart was widely known. But one judgment was ever present. Australia had been offered the chance to transcend its colonial heritage and the legacy of White Australia and had favoured the past over the future. And it is not that the many countries in the Global South don’t understand. They know only too well about a shared experience of Western imperialism and the long struggle for decolonisation which persists still in one form or another all over the world.

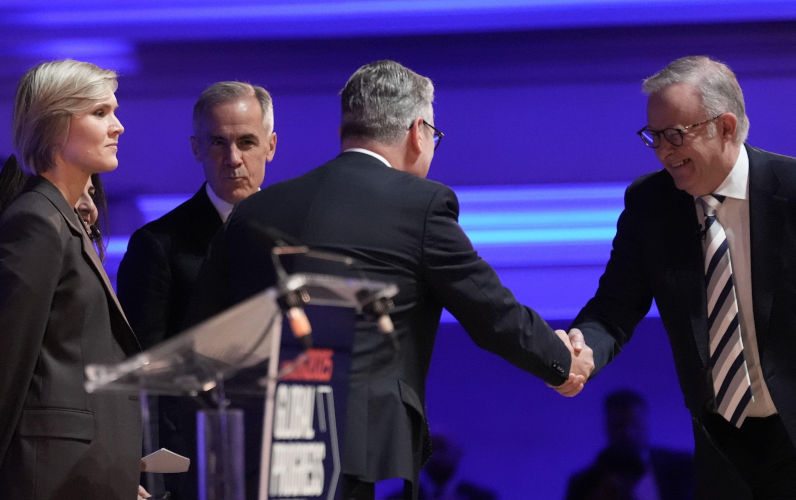

Albanese’s recent visit to Britain may have evoked less interest than the Voice referendum, but had it done so it would have fortified the common view of Australia. Having joined the leaders of the UK and Canada in their promotion of democracy, he then paid homage to our official head of state who is a hereditary aristocrat living on the other side of the world and who as a young man was complicit in the removal of Prime Minister Whitlam 50 years ago. He has never been called to account. His face is now appearing on all our new coins progressively released since late 2023, for all the world to see and wonder about their provenance.

And then there is our national flag dominated by the Union Jack which is known everywhere as Brand Britannia. Its history needs some explanation. It is a British colonial flag adopted just after federation. At the time, there were more than 50 British colonies with similar flags based on either the blue or the red ensign. They illustrated British sovereignty and colonial constitutional dependence. As decolonisation took hold, almost all the colonies adopted their own national flags. Raising them on their flag poles was often the climactic moment of achieved independence. Of those old relics of a departed empire, there only four left on flag poles in Tuvalu, Fiji, New Zealand and Australia, along with a bunch of the small and politically insignificant British overseas territories.

There have been numerous attempts to adopt a new national flag. There was talk of it to mark the bicentenary of settlement in 1988 and then again for the centenary of federation in 2001. But the only relevant gesture that has been made is to officially describe our flag as the “Australian blue ensign”. But that should not fool anyone and it certainly does not do so in all those nation states who are justifiable proud of their distinctive national standard .It is our own Flag Act of 1954 which, for the first time declared that the blue ensign had replaced the Union Jack as our national flag, which gives the game away. The preamble to the act declares that the Australian flag “is the British blue ensign”. All those right wing protesters who parade and march wrapped in the flag are both right and wrong – they are venerating what people all around the world know is a British colonial relic, but they are also right in appreciating that it is the flag of White Australia.

Much the same story can be told about the celebration of Australia Day on 26 January to mark the anniversary of the arrival of the First Fleet in Sydney Harbour. It has been very controversial and much contested for many years. For First Nations’ Australians and their many supporters, it is seen as Invasion Day. But that is only part of the story.

For many of us it seems odd to commemorate the arrival of more than 1000 convicts torn from country and kin by the operation of a vicious criminal code that placed the protection of property ahead of all other considerations. It’s a strange choice for a national day. The further intimation is that there is nothing that we Australians have achieved in all those following generations that can match what Britain did in arriving at the end of a long sea voyage. Soon after coming to power, Anthony Albanese declared that there would be no change as to when and how we commemorated Australia Day. The federal Opposition applauded the decision.

There are now so many reasons to doubt if our political leaders are able to come to terms with a rapidly changing world. They seem quite unable to carry through the final stages of our own variant of decolonisation.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.