Remembering my Palestinian father

October 16, 2025

In these awful times of genocide and massacre, I particularly remember my late Palestinian father.

Of course, I have never forgotten, even decades after his death, which changed our lives. My family: my Lebanese mother, brothers and sisters came to Australia, as we could no longer stay in Jordan where he worked while the civil war in Lebanon raged. All of us children had no passports, but Palestinian “travel” documents.

My father worked, as many other Palestinians did, in the United Nations Relief and Works Agency in Beirut, Lebanon, then later in Amman, Jordan. Some of my earlier memories are when he took me with him to work, and I played in the surrounding gardens kicking a ball, or browsing through stacks of UNRWA books that I couldn’t understand.

My father had me near him as he listened to the news on his short-wave radio. My mother couldn’t interrupt him while the news was on. He listened every hour, sometimes every half-hour. She had to time her questions or give up in frustration. Perhaps, by the age of 10, I memorised the UN resolution numbers 242 , 338 and so on, and it did not take me much longer to learn that they meant nothing. I understood that we live in a lawless world.

Before the Lebanese civil war began, my father would visit his mother in another suburb of Beirut every week without fail. Most of the time he would take only me, his eldest son, with him. He would spend the whole day there dressed in pyjamas, very relaxed. Sometimes we would sleep in her home overnight. She would put heavy blankets on me to protect me from possible cold, sometimes in the middle of the Beirut summer heat. I would wake up sweating and she would look at me, and ask if I was cold, if I needed more blankets!

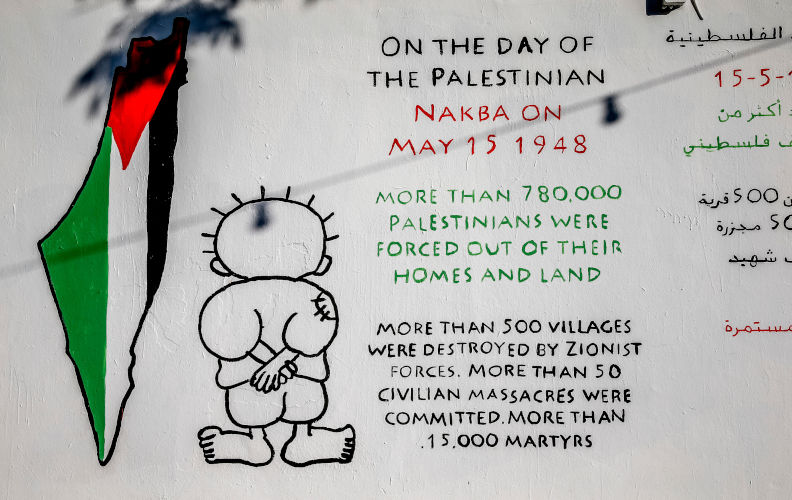

My father and his family were forced out of their home when he was 18. He was also the eldest son. In Palestine, it looks like he was a good swimmer and learned to play football, because he was good at both. His family escaped to Lebanon during the Nakba, and rented a house next door to the home where my mother lived.

My mother and father married despite initial opposition from both of their families. Even a civil war could not start an argument between them or set them apart. My father would help her with some housework at times when it was unusual for Arab men to do so, and would always support her and speak highly of her. After his death, my mother left her own family to look after us in Australia, and she has never forgotten him either .

When I read all the books, all the opinions, all the justifications on the Palestinian problem, I remember that my father and other Palestinians were forced out of their homes, and that saves me from the falsity of convoluted arguments.

My father was very peaceful. He was a mediator. He was honest. He never had a high position in his work, and I don’t recall him reading any books, but he was intelligent, sociable and thoughtful. Everyone trusted him and most people liked him. He was not a pacifist. He supported the Palestinian cause and Palestinian resistance. He also grew up alongside Jewish people and knew them as human beings. I think he might have had a Jewish girlfriend or friend, because his other Palestinian friends would tease him in front of me with questions about a Jewish girl that he knew and I would become a little annoyed on my mother’s behalf. I think that knowledge of the enemy was an essential difference for Palestinians who actually knew Palestine. I remember one of my father’s friends reciting the Arabic proverb, “We want to eat the grapes, not kill the guard”. It was the return to Palestine that mattered, not endless wars, or endless hatred. For us, their kids, the second generation of exiled Palestinians, we did not know Palestine. We only knew the Zionist enemy: an abstraction of colonialism and evil with powerful weaponry.

My father cared deeply about our education. He knew that for Palestinians, education is the only chance of survival. Neither he or my mother were helicopter parents. He never helped me with homework, and just nodded when I showed him good school results. One of the few times I saw him with tears in his eyes was when he failed to get us to school in Jordan, when we missed the start of the school term after he knocked on the doors of every private school and begged them to take us.

In my Palestinian grandmother’s house, I would jump on the old beds, a practice I could never dream of in my Lebanese grandmother’s house. She, despite, being equally loving , would chase me with a stick, if I or any other kid just brushed against the furniture. My father would engage his brother and friends in political and other conversations and I would listen. I liked the way he spoke and what he said. Truth did not feel subjective or relative. It felt concrete, real and necessary, like bread, water and bricks. My Palestinian grandmother, or perhaps my Palestinian aunt, had a large book. I remember its title, but not its author: “Biladona Falastin – Our country Palestine”. It was a boring book. It only listed the names of Palestinian families and their house titles. It was, at least for my previous self, the true record of the owners of that land.

I remember my father and I remember all Palestinians who like him love their children. I remember and will remember the thousands of Palestinian children who have been killed. I remember and I am thankful for those in the world with a conscience, including Jewish people, who stood against the ethnic cleansing and killing of Palestinians, spoke against it, or walked in demonstrations against it.

This is what I want to remember, because I would rather forget the rest. The Western governments who speak about laws and international order and human rights, but apply it only selectively for political advantage. The corrupt Arab governments that sold the Palestinian cause and got nothing in return. That segment of Palestinian society who think hate and religious bigotry is the answer to hate and religious bigotry. All of those who were silent, all those who see with one eye, all of those who did not look, all of those who looked and did not care.

Sometimes, I think my father and all Palestinians are unlucky. What right did these foreign powers have to interfere with our lives like this? What hypocrites talk about liberty and peace, then come to deprive us of it? Yet, we are lucky in different ways, that we are on the side of justice, but being on that side should never give us the right to act unjustly either. On the side of justice, we have beautiful and wonderful people to support us, and stand beside us, and let racists, haters, opportunists and hypocrites stand where they want to stand.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.