The migration debate in Australia

October 21, 2025

Australia’s population growth rate is returning to normal. Instead, of cutting migration, the solution to Australia’s housing crisis is to increase the rate of new dwelling approvals and completions.

Opposition to Labor’s allegedly high rates of immigration was a key element of the Liberals’ last election campaign. However, they lost and lost badly.

Nevertheless, less than six months since that election loss, Andrew Hastie, when resigning from that front bench of the Liberal Party, sought to make his opposition to present migration rates an issue yet again. According to Hastie, high overseas immigration made Australians “feel like strangers in our own home”.

Personally, I doubt that this changing nature of our society would worry many of us. I can remember Australia before the rapid surge in migration in the 1950s and 1960s, and my memory is that most of us welcomed the way migrants changed our cities to make them much more interesting. Migrants greatly enlarged our quality and variety of life and helped build our economy over the last 70 years or so.

However, where I suspect the critics of migration might strike a chord is the fear that migrants are adding to the housing crisis. And it is the cost of housing that is the key driver of unacceptable living costs.

But that hypothesis begs the question of how the rate of population growth compares with the rate of housing development.

Population growth

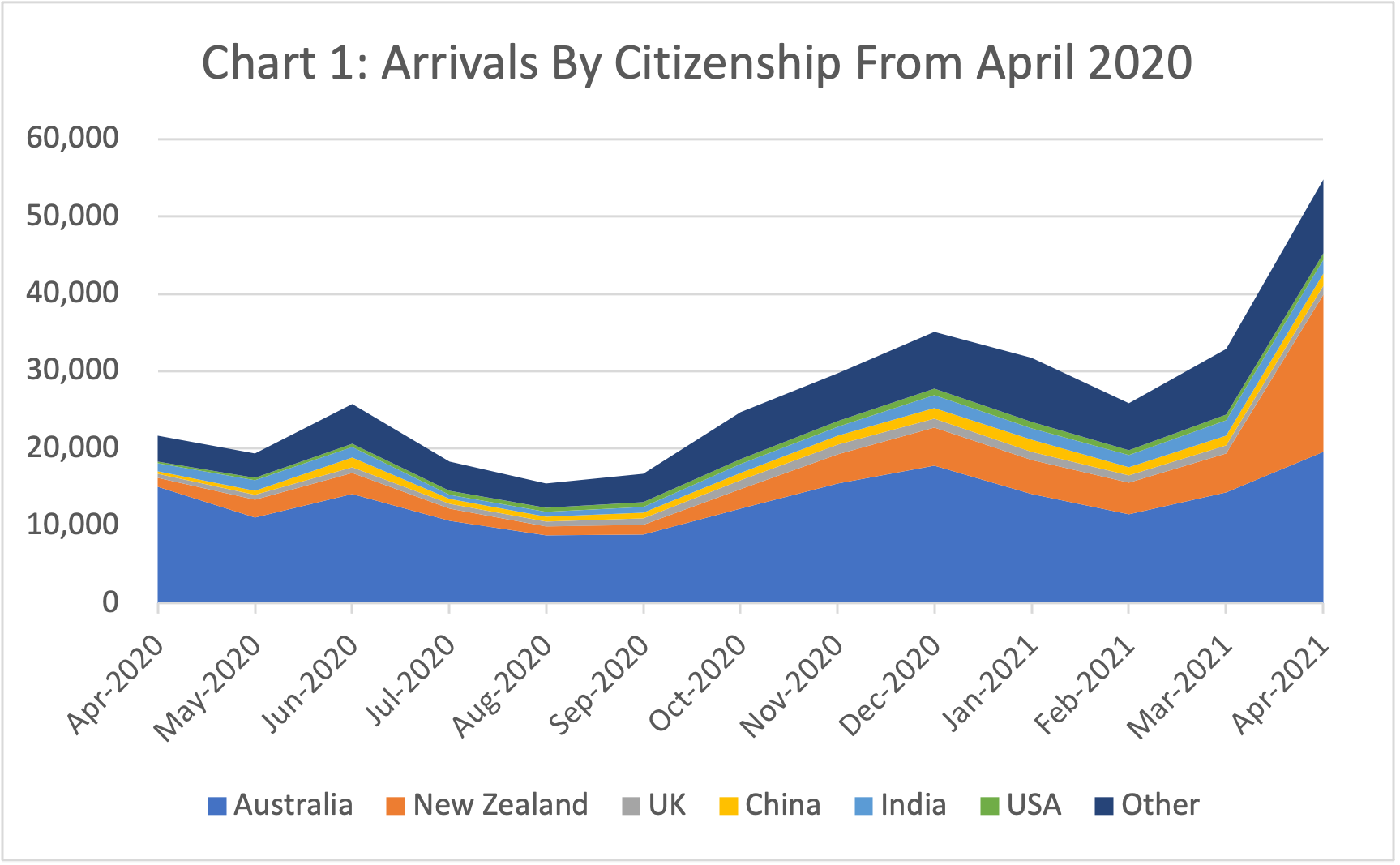

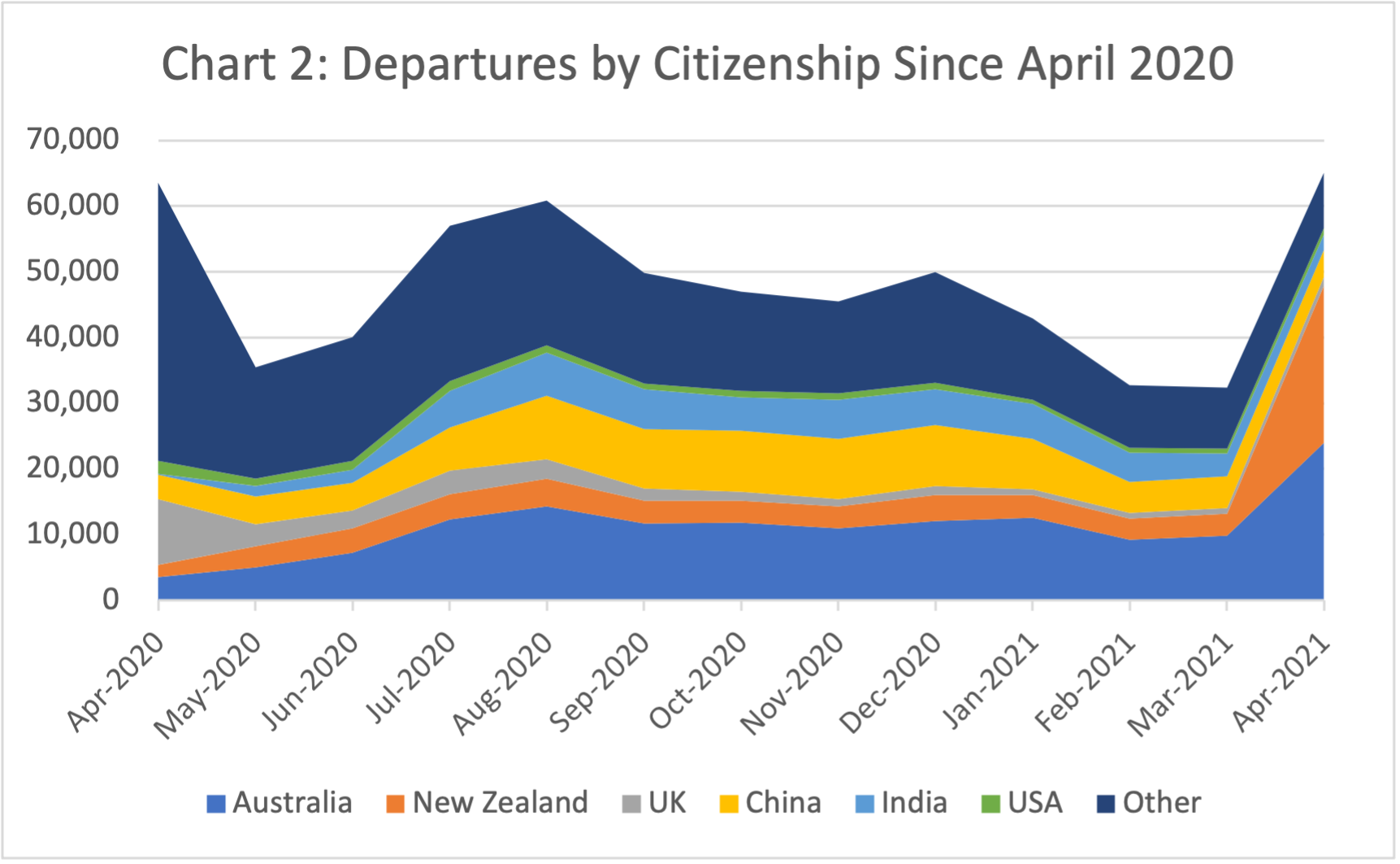

As can be seen from the chart below, population growth was close to zero during the COVID years due to net emigration. Subsequently, migration soared and recovered the lost ground, but migration and population growth are now dropping back to normal.

Indeed, the Treasury forecasts in their latest Intergenerational Report (2023) are that population growth will slow to an average of 1.1% per year over the next 40 years, compared to 1.4% per year over the past 40 years.

Further, it is somewhat strange that the Coalition parties are critical of the present rate of population growth. In fact, back in 2015 the Coalition’s intergenerational report projected that the population in 2025 would be almost a million more than has actually been realised. Even the Coalition’s last projection in 2021, just before they lost office, planned for a population size no smaller than what has actually happened.

In addition, it should be acknowledged that Australia is facing an increasing challenge from an ageing population. The number of elderly people who are dependent on support is increasing relative to the number of younger people who can be called upon to provide that support.

Also, Australian fertility rates are falling (below the reproduction rate), and without migrants the burden posed by an ageing population would be very much higher.

Recent population growth compared to new housing development

The data reveal that population growth can vary significantly from year to year. However, the variation in the number of new dwellings approved is much greater from one year to the next.

Therefore, in Table 1 below the additional population over around five years is compared with the number of new dwellings approved or completed over that same time period. What stands out is that over the most recent period, from the start of COVID (2019-20) to the latest financial year (2024-25), the number of new dwellings approved was equivalent to 54.7% of the increase in the population over that same period and the number of new completions was 54.5% of that population increase. While these rates were a bit lower than in other periods in this century, they were not all that different.

Table 1 New dwellings approved and completed relative to increase in population

What these data do not tell us, however, is the extent to which new dwelling approvals were where people want to live. In fact, we know that more approvals on the edge of major cities, some 60 km from the city centre, will not meet a lot of the new housing demand. Instead, many people want to live closer in, and that is why the median house price has surged from five times the median income in 2004 to eight times in 2024, and ten times in Sydney.

The counterpart of unaffordable home ownership is that if people live where they want to live, they are forced to rent. This has particularly affected young people. In 1981, 61% of Australians aged 25 to 34 were homeowners, but this fell to 21% in 2021.

If we want to restore home ownership, we need to change the planning and zoning systems to allow much greater urban infill. But reducing the number of migrants will not help much. Indeed, migrants play a major role in the building industries, and reducing migration could well add to the problems of housing supply.

Also, because migrants are more likely to be employed in industries like building and manufacturing, they have less need to locate closer to the centre of the metropolis. Instead, migrants are more likely to be housed in the outer suburbs where they are not putting pressure on housing prices.

Students and other temporary visitors

In fairness, perhaps the Coalition understands where migrants live, as they have not pushed to lower the intake of permanent migrants. Instead, the main thrust of the Coalition’s attempts to limit Australia’s migrant intake has been to limit temporary visa holders,

In 2023-24, as many as 465,000 were on temporary visas, far more than permanent visas (91,000), Australian citizen arrivals (60,000) and New Zealand citizens (51,000). Of these temporary visa holders, there were 207,000 international students, 80,000 working holidaymakers and 49,000 on temporary skilled visas.

Of course, most of these temporary visa holders will not stay in Australia and do not contribute to long-term housing demand. But it is the student intake, which is by far the largest group of temporary visa holders, that the political parties seem to be most focused on limiting.

The Albanese Government is now using so-called “planning allocations” to control the number of foreign students in each university. The government is also pushing universities to develop more student accommodation and is tying visa allocations to the availability of that student accommodation.

There is no doubt that universities have sought to increase their foreign student numbers. They say they were forced to do this because of government underfunding of their Australian students. Certainly, many Australian universities are struggling financially and even cancelling courses and laying off staff.

So if the government did act to significantly reduce foreign student visas, it seems likely that there would be considerable extra pressure on the Budget to provide additional funding to universities instead. And finally, cutting the number of foreign students would reduce the income from one of Australia’s most important export industries. Not something that governments normally seek to do.

In sum, the key to resolving Australia’s housing crisis lies in increasing the number of new dwelling approvals and completions, not in reducing the population growth which is not all that rapid.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.