'We can do this': Rio Tinto’s rapid switch to renewables shows path for quick exit from coal

October 21, 2025

You might be able to imagine the scene: An Australia sporting minister stands up in front of a vast audience to announce that something is simply not possible – it might be running 100 metres in 10 seconds, kicking a drop goal from 50 metres, or a swimming relay team beating a world record.

Behind the minister, on a big screen, there is a video of some sporting people doing exactly what the minister just said was not possible.

It was a similar vibe at the Brisbane convention centre last Friday (10 October), when the state’s energy minister slammed the brakes on the state’s energy transition, because he said it was going too fast, just as the biggest energy consumer in the state announced it was switching from coal to renewables in record quick time.

As we have written already, the Queensland LNP government’s new energy roadmap effectively shuts the door on new wind and solar projects in the coming five years. It says closing down coal generators under the previous government’s time frame would lead to blackouts, rising prices and economic ruin.

Its own documents highlight that the opposite is true. Nearly half of the 6.5 GW of new wind and solar capacity already locked in for construction in Queensland is destined to help power Rio Tinto’s giant smelters and refineries in Gladstone, allowing it to shut down the biggest coal generator in the state in just four years’ time.

How is this possible?

Paul Simshauser, the departing head of Powerlink and the former director-general of the state’s department of energy, says it is entirely feasible, and much work has already gone into preparing the infrastructure — new transmission and other grid needs — to enable the switch from coal to wind, solar and storage.

“I don’t think we need to be panicking,” Simshauser says in last week’s episode of Renew Economy’s weekly Energy Insiders podcast. “We can do this.”

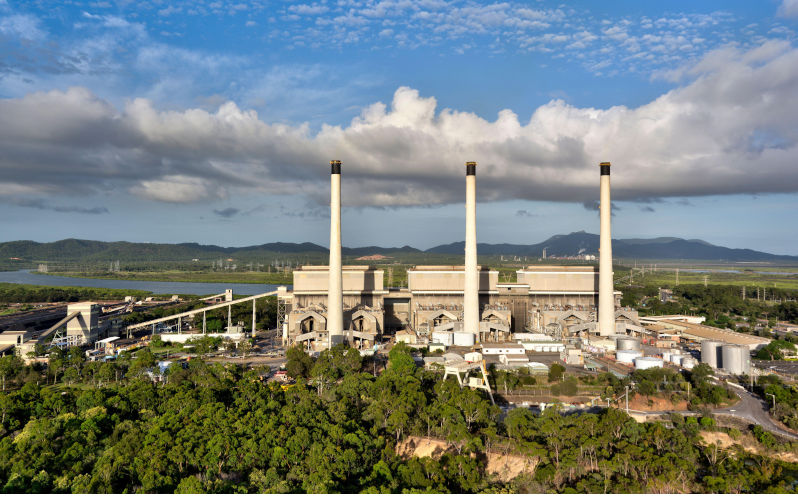

Simshauser points to the fact that the 1680 megawatt Gladstone coal generator — the state’s biggest — is nearly 50 years old and operates at a capacity factor of less than 50%. And he says that can largely be replaced by wind.

“If you take the average daily production of Gladstone power station and compare it to the average daily production of the couple of wind farms that are in reasonably close proximity, the shape of the output is eerily similar,” he says.

“There’s an enormous number of batteries that have reached financial close and are under construction here in Queensland. There’s a pipeline up here that is mind-blowingly large.

“We’ve obviously got a lot of solar… so, do I worry about the Gladstone closure? No, I think there will be enough coming through the pipe.”

Simshauser, it should be noted, was speaking to Energy Insiders the day before the new Queensland energy roadmap was announced, and a week after Rio Tinto had announced that Gladstone would likely close in 2029, six years ahead of schedule, because it said the giant assets had no future if they had to rely on fossil fuels.

Rio Tinto has made the Gladstone transition possible because it has already locked in contracts for several large wind, solar and solar battery projects, some of whose paths have been made easier by winning underwriting agreements in the federal government’s Capacity Investment Scheme.

Rio Tinto’s needs for further “firming” capacity will likely be met by a new tender for gas capacity, and Powerlink has been given approval to go ahead with transmission upgrades in the area.

“Gladstone outputs about 6500 gigawatt hours a year,” Simshauser says. “So a couple of good wind farms can knock that off. And there’s a couple that I think have got a very good chance of reaching financial close, and can start to ramp up as Gladstone is ramping down.”

Rio Tinto is not the only big miner hastening to renewables to ensure the future of their huge and immensely profitable mining and smelting operations.

BHP, for instance, has signed a couple of landmark contracts for a combination of wind and battery storage to power the bulk of its giant Olympic Dam copper mines and smelters in South Australia.

In the Pilbara, Andrew Forrest’s Fortescue is going even harder – aiming to eliminate the burning of fossil fuels altogether by 2030 by switching from gas and diesel generation to wind, solar and battery storage and electrifying its entire mining operations.

Fortescue chief executive Dino Otranto says rapid technology changes — particularly in battery storage — are making that goal a lot easier to achieve, and says it makes economic sense because of the massive fuel savings.

[You can hear an interview with Fortescue’s Otranto in the latest episode of Energy Insider here: Energy Insiders Podcast: Fortescue’s bold charge to real zero by 2030]

Back in Queensland, Powerlink’s Simshauser is more concerned with getting ready for the next coal closure. The LNP has scrapped Labor’s closure times and insisted that the remaining state-owned generators will run till the end of their technical life, and possibly beyond.

Simshauser wonders how this will be possible.

“There’s been about 10 or 11 coal-fired generators that have that have closed over the last decade and a half, and their average age at closure was 44 years.

“If you take our existing fleet, it’s 38 years. So, some of these machines are probably slightly better built than the ones that havee gone. But do I think we ought to be getting on with the job?

“Yes, I do, because there will be… mechanical engineering limits to what you can do with these plants. We know there’s going to be market limits.

“One of the big risks to all of these, and if I can just refer to it as inflexible generators, is if we don’t work out how to move them around adequately, we are going to find ourselves, for weeks at a time, in the middle of the day, where there was literally nowhere for the power to go.”

That, of course, relates to the solar duck curve, and the massive growth in rooftop PV which — under the government’s own estimates — will grow to about 13 gigawatts by 2035 – significantly more than the average demand and even more than the state’s maximum demand.

In the meantime, the state government has followed through with its promise to repeal the state’s renewable energy targets, by introducing legislation to state parliament. It is also scrapping three special committees formed to advise the government on the transition to renewables, which is clearly now not supposed to happen.

Simshauser also points to the potential of the distributed network to support new renewables, particularly given that soaring costs for transmission (he says they have at least doubled in recent years) makes building a new backbone out of reach. “They don’t stack up any more,” he says.

He is also open-minded about which technology will deliver the critical “system strength”, the grid services traditionally delivered by synchronous generators.

Powerlink has identified the need for nine synchronous condensers, big spinning machines that do not burn fuel, but has only put in an order for two, maybe four at a stretch.

That’s because the company is still open to what the battery technology providers can do on with grid-forming inverters.

“We want to try and give the market as much time as possible to come in and actually provide these services in other ways,” he says. That includes using gas turbines installed with a clutch (so they don’t burn fuel) which is being tested in Queensland.

In the meantime, he says the state should get cracking on new developments. To go back to the sporting analogy that we started with:

“We’ve got to get our supply side to the gym pretty quickly, get working pretty hard on all the flexible, firming pieces of kit we need so that we can manage those (coal) exits gracefully rather than awkwardly.”

Climate Change Authority chair Matt Kean, a Liberal who led the creation of NSW’s even more ambitious coal replacement plan, questions the sanity of Queensland’s move and how it will be able to keep the lights on as the coal generators age.

And Stephanie Gray, from the Queensland Conservation Council, also questions how the LNP can possibly retain the previous government’s emissions reduction targets if it brings a halt to the green energy transition.

Republished from Renew Economy, 17 October 2025

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.